LIFE AND CAREER

Antonio Stoppani was born in Lecco on August 15, 1824, to Giovanni Maria Stoppani and Lucia Pecoroni. He was the fifth of sixteen children. His father, born in Zelbio, a small village near Como, was involved in the trade of colonial goods, producing and selling chocolate and managing a candle factory. Thanks to this activity, the economic conditions of the Stoppani family were adequate to enroll their numerous sons and daughters into a regular education, strongly guided and encouraged by their mother Lucia, who played a fundamental role in Antonio’s cultural growth (Cornelio, 1898).

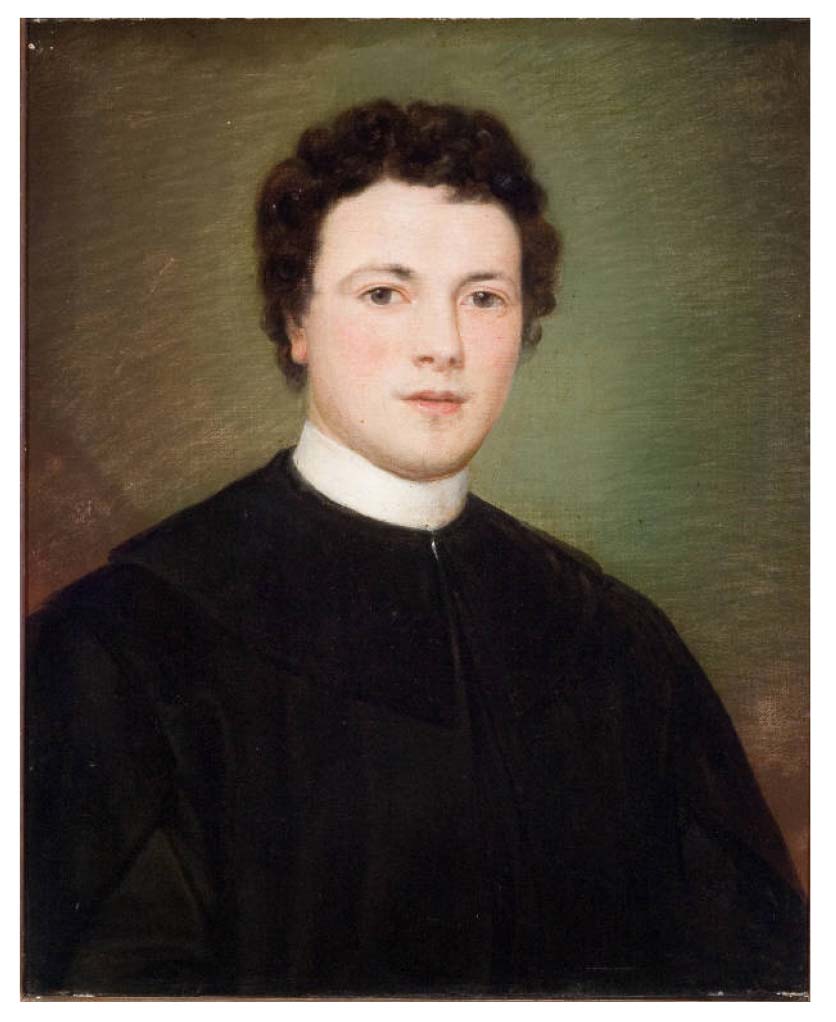

In 1836, young Antonio, affectionately nicknamed “Tognino” (Fig. 1), began his education at the Seminary of Castello near Lecco at the foothills of the San Martino mountain, Grigne Group. He later moved to San Pietro Martire in Seveso to study rhetoric and humanities, then to Monza in 1843 to pursue philosophy, and finally to the Seminario Maggiore in Milan in 1845 to study theology. While in Monza, he was introduced by Alessandro Pestalozza (Carotti, 2015) to the philosophy of Antonio Rosmini. Declared a Blessed Servant of God in 2007 (De Giorgi, 2017), Rosmini was a theologian and philosopher from Rovereto whose ideas deeply influenced Stoppani’s life (Zanoni, 2014; 2019). In March 1848, Stoppani actively participated in the Five Days of Milan (March 18-22, 1848), a crucial uprising during the European Revolutions of 1848. During these days, the citizens of Milan revolted against the harsh Austrian government of the city, compelling Marshal Josef Radetzky and his troops to withdraw from the city. This insurrection, characterised by fierce street battles, barricades, and the united efforts of various social classes, became a crucial event in the Italian unification movement.

- A young Antonio “Tognino” Stoppani (1848) (Lombardia Beni Culturali, Pubblico dominio, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82417512).

The Seminario Maggiore, where Stoppani resided, became a refuge and provisional headquarters for both combatants and civilians. Stoppani played a notable role by drafting and disseminating proclamations to rally the population. These messages were ingeniously distributed using paper hot air balloons - a method devised by Stoppani and his colleague Cesare Maggioni. The balloons, approximately two meters in diameter and crafted in white or tricolour patterns (red, white and green), carried reports, government instructions, and messages urging citizens to rise up against the Austrian invaders.

As one contemporary account describes: “Stoppani provided paper, glue, and twine to the younger companions, armed them with scissors, and together they crafted the balloons. […] Twelve larger balloons followed the first one, in addition to smaller versions” (Zanoni, 2014). This creative contribution highlighted Stoppani’s resourcefulness and commitment to the cause of liberation.

A few months later, Stoppani joined the battle of Santa Lucia in Verona on May 6, 1848, and stayed in the nearby village of Sommacampagna for about one month to assist the wounded fighters, in the framework of the First Italian War of Independence (Centro Studi, 2017). After the 1848 campaign, he returned to the seminary, where he was ordained in June. Just days after celebrating his first Mass, he began teaching Latin grammar at the abovementioned Seminary of San Pietro Martire. Among his students, rumours spread about his passion for natural sciences and his experiments, such as “burying mice to obtain their skeletons, dissecting them, and similar pursuits” (Cornelio, 1898). During summer holidays, Stoppani engaged in geological investigations and in search of fossils in the quarries around Lecco, particularly in Pliocene deposits at San Colombano, Miradolo, near Santa di Valmadrera, Suello, and Ésino. These activities provided scientific material for one of his earliest works (Stoppani, 1857). Stoppani’s enthusiasm and expertise were so notable that the sites he explored were left almost devoid of fossils, leading foreign geologists to refer to such locations as Stoppanisés - a tribute to his exhaustive collection efforts (Cornelio, 1898; Clerici, 2018).

At the end of 1853, Stoppani, along with many other dissidents, was expelled from the archdiocesan seminaries by order of the Austrian government. Austrian authorities also blocked his subsequent appointment as vice-rector of the Calchi-Taeggi College. This event was decisive in Stoppani’s youth, marking the beginning of a challenging period in his life. Uninterested in parish ministry, he took on private tutoring positions in Como and Milan, including a role with the prominent Porro family to educate their son, Gian Pietro. Tragically, Gian Pietro would later lose his life in 1886 during an expedition in Harar, Ethiopia (Paleologo Oriundi, 2009; Surdich, 2016).

During this time, Stoppani also focused on organising his extensive fossil collection, which he presented to Franz Ritter von Hauer (1899), a geologist affiliated with the Kaiserlich Königlichen Geologischen Reichsanstalt (KKGR). Naively, Stoppani offered to create an exact catalog of his collection “for [Hauer] to use at his pleasure” (Pantaloni, 2024).

GEOLOGICAL AND PALAEONTOLOGICAL STUDIES

In 1857, Antonio Stoppani published his first major work: Studi geologici e paleontologici sulla Lombardia. In the preface, he quotes Dante’s Paradiso (Canto I): “The glory of Him who moves everything penetrates and shines throughout the universe”, foreshadowing the theme of reconciliation between faith and science that would permeate his life. In this book, Stoppani asserts,“faith […] welcomes the sciences as friends, supports them, illuminates them, but does not invoke them as auxiliaries, nor does it fear them as enemies”.

Stoppani argues that geology provides “arguments in support of revelation” and suggests that stratigraphic data can affirm the concept of a universal flood, though he admits that the data best suited to support this theory were, at the time, “the most disputable”.

In the second part of this book, Analisi parziale dei terreni lombardi in serie discendente lungo la linea dello spaccato, he explored Lombardy’s geology, proposing a gradual uplift process, aligning with Lyell’s gradualism and contrasting with Cuvier’s catastrophism. Stoppani attributes the orogenic phenomenon to two potential systems: the uplift systems of the Pyrenees and Apennines or to the main Alpine uplift (Stoppani, 1857).

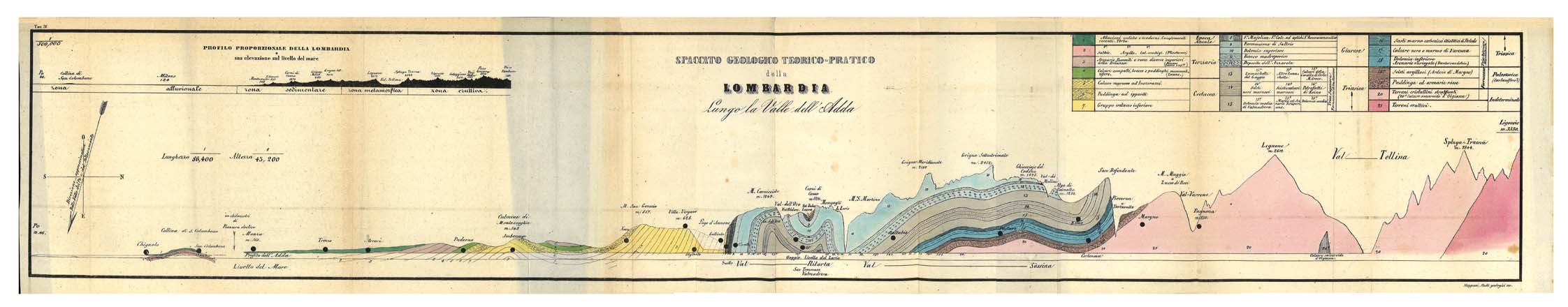

At the time, the geological structure of Lombardy was only partially understood. Stoppani constructed a comprehensive stratigraphic sequence of Lombard formations, which remains largely valid today. His meticulous work aroused the admiration of Franz Ritter von Hauer who encouraged Stoppani’s research and supported his nomination as an associate of the Geological Institute of Vienna (Mercalli, 1891). This recognition established Stoppani as a keen observer of Alpine tectonics and an insightful palaeontologist. The book includes a detailed geological cross section encompassing the Adda Valley, the Grigne massif, the Valsassina, Mount Legnone, and the Valtellina (Fig. 2). Stoppani’s stratigraphic scheme identifies Pliocene units at San Colombano, followed by Miocene formations in Brianza, Eocene calcareous, arenaceous, and conglomeratic units, Mesozoic strata, and ultimately, Carboniferous terrains, distinguished by the Verrucano Lombardo and the crystalline basement (Stoppani, 1857).

- Theoretical and practical geological section of Lombardy along the Adda Valley (from Stoppani, 1857). Courtesy ISPRA Library.

The third part of the book delves into palaeontology, providing descriptions of such precision that contemporaries acclaimed Stoppani as “not merely a follower of others’ work, but a true pioneer of Lombard palaeontology”. However, Stoppani diverged from prevailing views by attributing faunal extinction events to local-scale occurrences, whereas scientists like Georges Cuvier (1822) associated them with global extinction events. Furthermore, Stoppani did not fully embrace the nascent principles of palaeontology as a tool for stratigraphic correlation, which were gaining prominence in the early 19th century.

The publication of Studi geologici e paleontologici sulla Lombardia consolidated Stoppani’s reputation within the Italian scientific community and granted him access to the collections of the Civic Museum of Milan (Cornelio, 1898; Zanoni, 2019). He was subsequently inducted into the Lombard Institute of Sciences, Letters, and Arts and became a founding member of the Geological Society of Milan, established in 1856 under the auspices of the Austro-Hungarian Geological Survey to foster geological research within the Empire’s provinces. This society evolved into the Italian Society of Natural Sciences in 1860, attracting leading Lombard scientists, including Antonio and Giovanni Battista Villa, Emilio Cornalia, Giulio Curioni, Giovanni Omboni, and Giuseppe Balsamo Crivelli (Zocchi, 2011). After resigning his position at Porro family in 1857, Stoppani assumed the role of spiritual director of Milan’s male orphanage and custodian of the Ambrosian Library, where he continued to publish several geological papers. Following the liberation from Austrian domination after the Second Italian War of Independence (1859), he received authorisation to teach Natural Sciences. In 1861, he was appointed professor of geology at the University of Pavia, consolidating his academic career (Zanoni, 2014; 2019).

On November 27, 1861, Antonio Stoppani delivered his inaugural lecture at the University of Pavia titled Priorità e preminenza degli italiani negli studi geologici. Published in 1862, the lecture highlighted the pioneering contributions of Italian scientists to the field of geology. Stoppani asserted that Italy held “the honor of priority in geological and palaeontological investigations, having also preceded foreign scientists in a multitude of observations and interpretations that remain valid and are increasingly corroborated today”. He concluded his lecture with a reference to Antonio Rosmini: “If human minds achieve consensus in ideas and opinions, this intellectual accord immediately influences life, fostering benevolence among all, and creating the unity within which peace and social strength reside” (Stoppani, 1862).

In 1859, Stoppani expanded his Studi geologici e paleontologici sulla Lombardia with a paper titled Rivista geologica della Lombardia in rapporto colla Carta geologica di questo paese pubblicata dal cavaliere Francesco de Hauer published in the Proceedings of the Italian Geological Society of Milan (Stoppani, 1859; Zocchi, 2011). In this work, Stoppani observed that earlier geological endeavors were hindered by“adverse circumstances, […] isolation, and limited resources,” whereas more recent studies were refined due to “the more favorable nature of the undertaking” and new geological observations, complemented by the research of foreign geologists (Zanoni, 2014). Stoppani classified the uplift of Lombardy as belonging to the Main Alpine Orogeny, chronologically succeeding the deposition of Pliocene sediments. While he maintained the primacy of stratigraphic principles over palaeontological methods - denying a direct chronostratigraphic significance of fossils - palaeontology remained a principal focus of his scholarly interests.

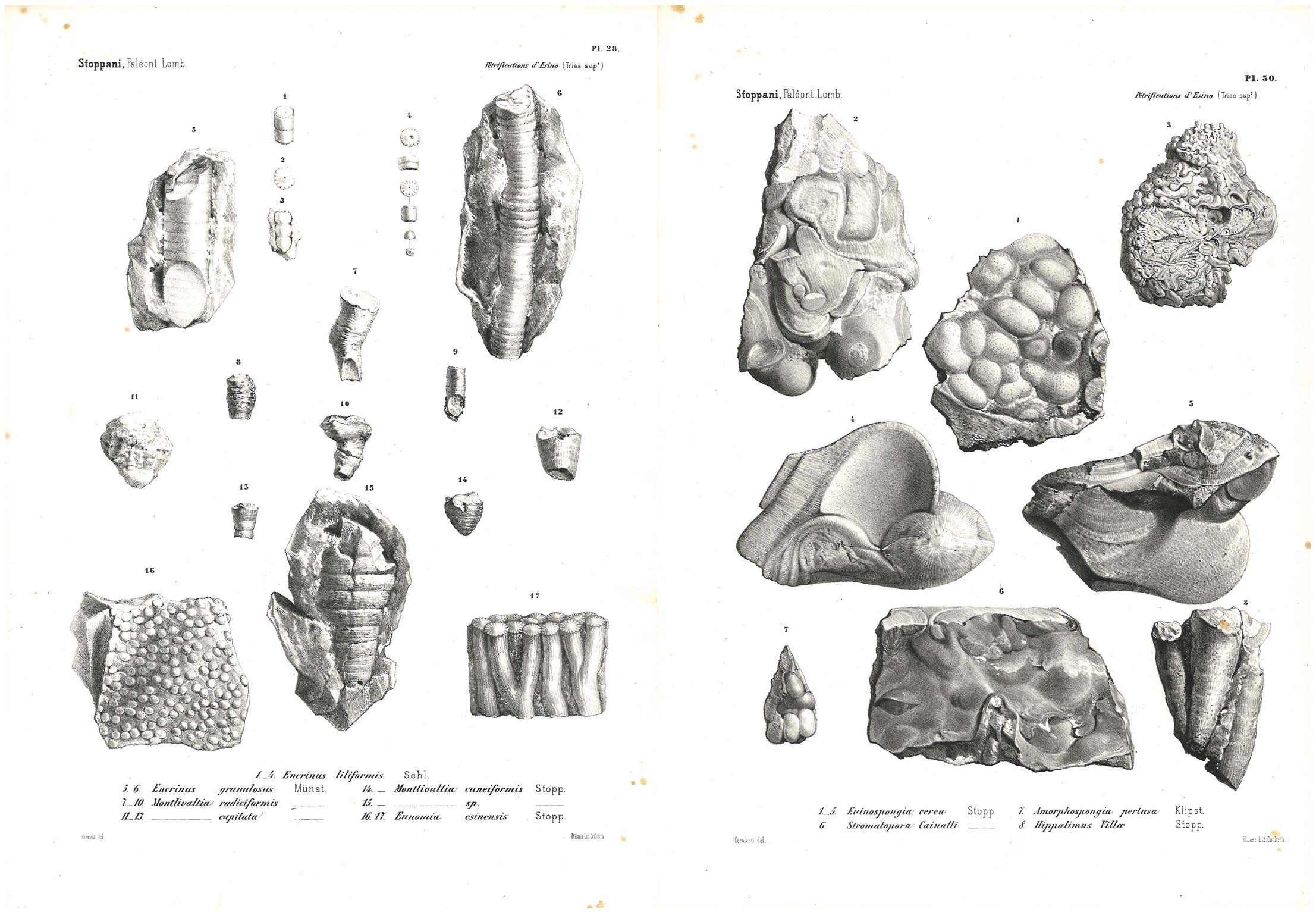

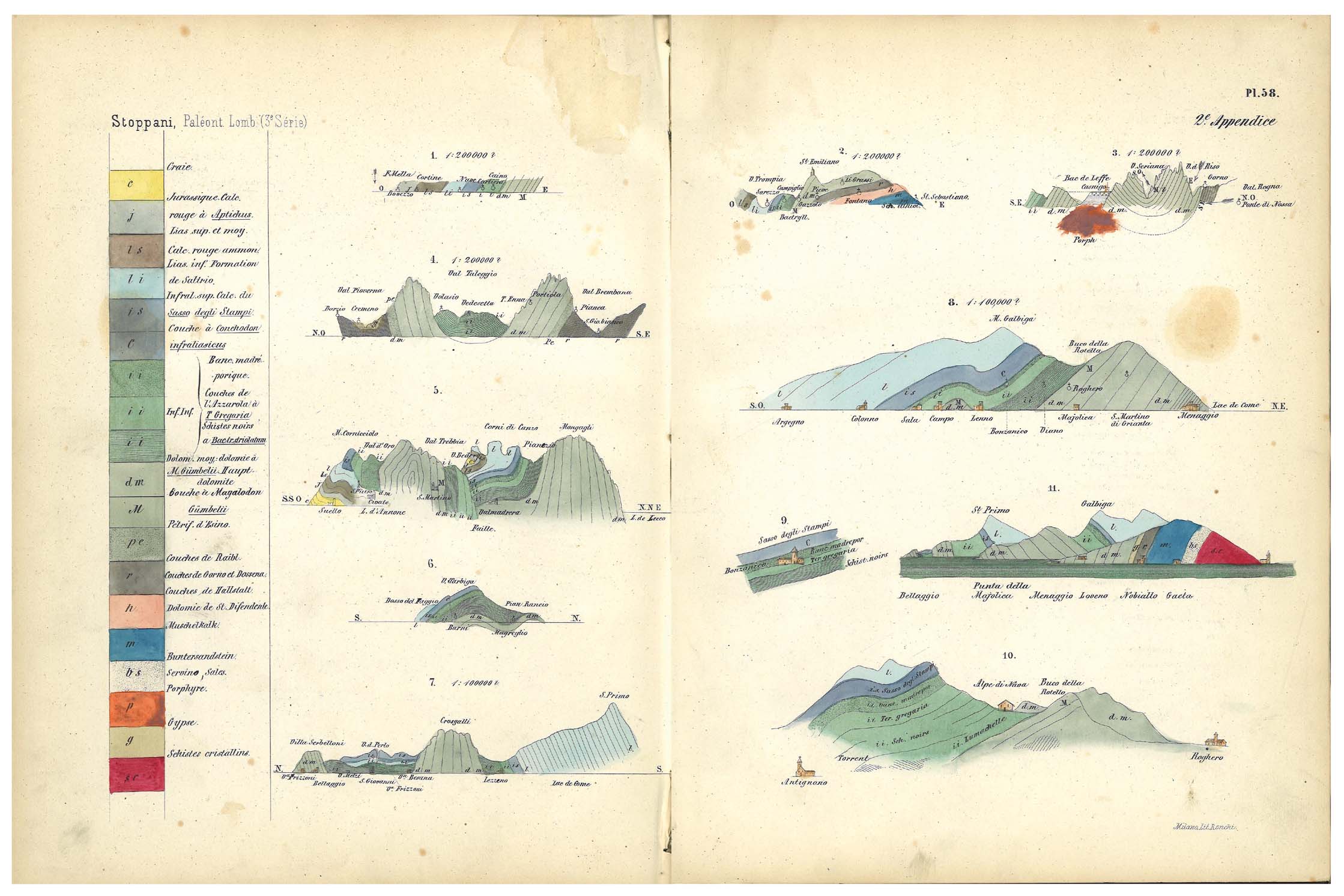

Between 1858 and 1881, Antonio Stoppani embarked upon a monumental palaeontological endeavor with the publication of the Paléontologie Lombarde ou description des fossiles de Lombardie publiée à l’aidé de plusieurs savants, a series of concise monographs focused on specific palaeontological subjects. Stoppani authored volumes on Triassic fossils from Ésino (Stoppani, 1858-60a) (Fig. 3) and the fossils of the Avicula contorta beds (Stoppani, 1858-60b) (Fig. 4).

- Palaeontological plates from the Volume I - Les pétrifications d’Ésino, ou Description des fossiles appartenant au dépôt triasique supérieur des environs d’Ésino en Lombardie - of the series Paléontologie Lombarde ou description des fossiles de Lombardie. Courtesy ISPRA Library. On the left: crinoids (Encrinus liliformis and Encrinus granulosus) and corals (Montlivaltia sp. and Eunomia esinensis). On the right: Evinospongia cerea Stopp., Stromatopora Cainalli, Amorphospongia pertusa and Hippalimus villae Stopp. It is noteworthy that Evinospongia cerea, previously assigned by Stoppani to the Spongiidae family, has been reinterpreted as a product of palaeokarst.

- Stratigraphic scheme and geological cross-sections contained in the volume Géologie et paleontologie des couches a Avicula contorta en Lombardie (Stoppani, 1858-60b). Worth of note is the watercolouring of the plate. Courtesy ISPRA Library.

Further contributions from Emilio Cornalia and Giuseppe Meneghini enriched the series. The former author published the second part of the volume devoted to the Mammifères fossiles de Lombardie (Cornalia, 1858-71), while the latter devoted his researches to publish a Monographie des fossiles du calcaire rouge ammonitique (Lias supérieur) de Lombardie et de l’Apennin central (Meneghini, 1867-81).

The project initially involved Abramo Massalongo from Verona (Alippi Cappelletti, 2008), but his untimely death tragically prevented his participation. This serialised undertaking, primarily funded by Stoppani’s family, also received crucial support from Quintino Sella and the Ministry of Public Education. Stoppani aptly described this venture as “audacious,” driven by his frustration that “geologists of Vienna,” with their authority to study Italian territories, often disregarded Italian contributions, considering them intellectually subaltern. The project’s prolonged timeline, stretching from 1858 to 1881, was due to several factors, including the disruption caused by the Second Italian War of Independence (1859) and substantial delays from collaborators like Emilio Cornalia, whose contributions were delayed for twelve years.

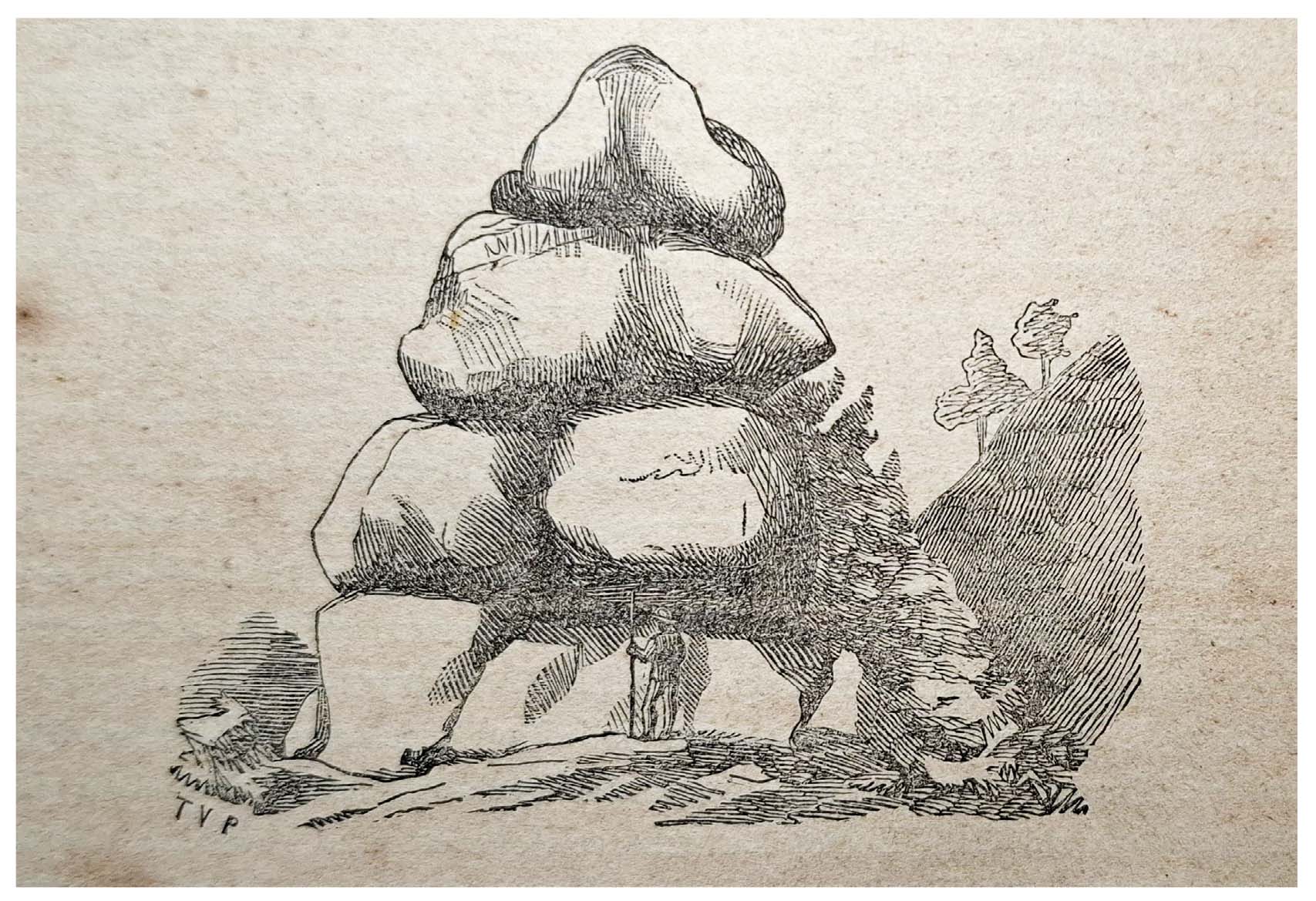

- Trachytic spheroids with prismatic base, on the Cimini Mountains above Viterbo (Lazio) (Stoppani, 1870). Courtesy ISPRA Library.

THE SEMINAL WORK “CORSO DI GEOLOGIA”

In 1861, strongly supported by Francesco Brioschi (Raponi, 1972), Stoppani assumed the Chair of Geognosy and Applied Mineralogy at the Istituto Tecnico Superiore of Milan, the first Polytechnic school in Italy (Visconti, 1998). During this period, he commenced the drafting of Note per un corso annuale di geologia, published in three volumes (Stoppani, 1865a, 1867, 1870). This work garnered significant acclaim, with Nuova Antologia recognising it as “one of the most serious scientific contributions to appear in Italy” (Zanoni, 2014). Similarly, the Royal Geological Committee’s bulletin, while acknowledging certain reservations, commended the work for its accurate observation of natural phenomena and its innovative approach towards achieving definitive geological results (R. Comitato Geologico, 1870).

It is important to remember that in an appendix to the Note per un corso annuale di geologia Stoppani expresses his skepticism about Charles Darwin’s theory of evolutionism (Darwin, 1859). Although he recognised an important scientific value in the progressive development of fossil species over time, he did not support the evolutionary idea because, in his view, the fossil record lacked documentation of a slow and gradual transition of species. Quite apart from an understandable religious prejudice, it should be noted that it was only in the late 1870s that Darwinian theory began to be consolidated, especially thanks to the important developments of palaeontological knowledge.

Stoppani’s criticism of Darwin’s theory never went beyond brief ironic references to the origin of man. According to Stoppani, the basic error of the theory of evolution was to regard man as a common animal species, and as such lacking in intellectual and moral nature.

Stimulated by the success of the first edition, Stoppani undertook a comprehensive revision and expansion, culminating in the publication of Corso di Geologia, in three volumes, published between 1871 and 1873. This expanded edition, considered the first comprehensive Italian geology textbook, built upon the foundations laid by Scipione Breislack’s Introduzione alla Geologia (Breislack, 1811) and Leopoldo Pilla’s Trattato di Geologia (Pilla, 1847-1851).

In the introduction to Dinamica Terrestre, the first volume of Corso di Geologia (Stoppani, 1871), Stoppani defined geology as the science that “seeks to elucidate the history of matter and life,” describing it as “the history of the Earth derived from comparing the effects produced by present-day causes with the evidence of those same causes acting in the past”. This definition clearly reflects his adherence to the principle of uniformitarianism, a foundational concept in geological thought originally proposed by James Hutton and later developed by John Playfair and Charles Lyell. The volume focuses on terrestrial dynamics, offering a detailed examination of geological processes driven by atmospheric agents, with the aim of understanding their historical impact. Stoppani systematically divided the study into external and internal terrestrial dynamics. External dynamics included the analysis of atmospheric, oceanic, and meteorological circulation, with particular attention to processes such as erosion and continental erosion, fluvial transport and deposition of marine delta. Conversely, internal dynamics explored the circulation of deep and surface waters.

The second volume - Geologia stratigrafica (Stoppani, 1873a) - delved into the realm of stratigraphic geology, meticulously examining geological phenomena as evidenced by continental and marine stratified and fossiliferous deposits, crystalline rocks (including granite interpreted as a lava), metamorphic overprint and the principles of superposition and lateral continuity. Stoppani emphasised the critical role of fossils in establishing the relative ages of geological strata. While acknowledging the occurrence of stratigraphic anomalies such as discordances and faults (faille in French), he deemed the Italian term faglia (fault) as a “Gallicism” to be avoided, a suggestion that was not accepted by the Italian scientific community.

The third volume - Geologia endografica (Stoppani, 1873b) - focused on endogenous geology, exploring the forces originating within the Earth and their surface manifestations. Stoppani analyzed the processes of crystalline rock formation and transformation, attributing them to the action of high-temperature water under lithostatic pressure.

Stoppani also delved into the realm of volcanology, aligning his theories closely with those presented by George Julius Poulett Scrope in his seminal work Considerations on Volcanoes (Poulett Scrope, 1825). He adhered to Scrope’s theory of volcanic cone formation through successive layers of ejected material (Poulett Scrope, 1862), explicitly rejecting the outdated “Uplift crater” theory of Leopold von Buch (1820). While acknowledging the presence of internal uplift forces, he linked them to a central heat source deep within the Earth. Furthermore, he established a clear connection between vertical movement of the Earth’s crust, fault systems and volcanic activity, illustrating this relationship through detailed diagrams as a model for the generation of mountain belts.

However, Stoppani allegedly linked the (unproved) subsurface hot water dynamics to volcanic activity. Notably, he identified a “great linear system” connecting volcanic complexes, such as the Phlegraean Fields and Vesuvius, as part of a broader chain that he attributed to the Apennines and Tyrrhenian volcanoes, the evidence of which had already been made explicit, as he reports, by Giuseppe Ponzi (1864). The volcanoes are aligned along a depression (elsewhere also called a syncline) with open fractures that allow the ascent of magma, flanked by two parallel chains: the Apennines and the coastal chain (catena littorale).

Stoppani further proposed that orogenic events and crustal deformation are driven by volumetric changes within rock masses, specifically attributed to the calorico, a sort of unspecified source of internal energy and chemical reactions and their associated thermal effects. Furthermore, he made significant contributions by advocating for the biogenic origin of certain mineral deposits, including iron ores, sulfur, gypsum, and dolomite. Notably, he also recognised the organic genesis of petroleum resources (discussed in detail subsequently).

Although the Corso di Geologia did not introduce entirely novel concepts, it successfully synthesised and adapted ideas from the leading British geological school to the specific geological contexts of Italy, demonstrating a solid knowledge of the discipline. Beyond his deep naturalistic insights, Stoppani’s work incorporated philosophical reflections on the limitations of human knowledge within the field of geology. He posed profound questions regarding the ability of science to address “the great questions of origins” or to “reach the finite boundaries of time and space.” These reflections reveal his belief that scientific investigation ultimately serves to reinforce faith.

This landmark work firmly established Stoppani as a founding figure of Italian geology. It provided a comprehensive framework that profoundly influenced the study of Earth sciences in Italy for generations to come, despite many of his geological concepts being based on fixist theories.

STOPPANI AND THE GEOLOGICAL MAP OF ITALY

Stoppani also played an important role in the discussions that developed for the project of the Geological Map of Italy, started in 1861 (Corsi, 2003, 2007; Pantaloni, 2014; Ercolani, 2017).

Following the unification of the Kingdom of Italy, a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the peninsula’s physical, geographical, and geological attributes became paramount for accelerating industrial development. In-depth investigations into the nation’s geological structure and morphology were deemed crucial for the successful implementation of mining activity, land reclamation projects, railway construction, and industrial infrastructure development.

In fact, immediately following Italian unification, the project of the geological map of the kingdom was prioritised, obeying the standards suggested by Felice Giordano in a letter of October 19, 1860, to the Minister of Agriculture, Industry and Trade (Cocchi, 1871) and codified by Quintino Sella in his famous memoir (Sella, 1862). Stoppani, a close friend and collaborator of Sella, played a significant role since its inception in 1861 (Pantaloni, 2011; Dal Piaz, 2024; Scoth et al., 2024). In collaboration with his pupil Torquato Taramelli (Console, 2024), Stoppani advocated for the establishment of a national geological institute, modeled after German and English institutions, to oversee the geological survey. This model emphasised the central role of geologists, palaeontologists, and academics. This proposal faced opposition from Quintino Sella, Felice Giordano and Giulio Axerio (Corsi, 2003) who favored placing the project under the purview of a specialised section within the Corps of Mines, mirroring the French model. This alternative emphasised a public service model centered on the expertise of mining engineers and of the mining industry.

While acknowledging the practical applications of the geological map, Stoppani and Taramelli stressed the importance of a geological map founded on rigorous stratigraphic and palaeontological investigations, coupled with comprehensive chemical and microscopic analyses. These investigations were to be conducted by professionals possessing a deep understanding of geology and topography. They argued that these characteristics were not merely supplementary, but rather fundamental to the effective industrial and economic utilisation of the geological map (Lupi et al., 2024). Both Taramelli and Stoppani exhibited a critical, and sometimes openly polemical, perspective on the efforts to construct the geological map of the Kingdom of Italy (Scoth et al., 2024). It is worth noting that the personnel responsible for the field surveys of the Geological Map were provided with financial support from the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Trade to attend a three-year mining specialisation program abroad. They trained at prestigious institutions such as the École des Mines in Paris, the Royal School of Mines or the Geological Survey in London, the Bergakademie in Berlin, or the École des Arts et Manufactures et des Mines in Liège, Belgium (Brianta & Laureti, 2006; Brianta, 2007). During this period, the mining engineers refined their expertise in areas such as microscopy, optical petrography, palaeontology, and mineral resources. This advanced training is well reflected in their publications and cartographic work. (e.g., Baldacci, 1885; Lotti et al., 1884; Franchi, 1898; Zaccagna, 1896; Zoppi, 1888).

The geological surveying for the production of the Geological Map of Italy began with the Institution of the Royal Geological Survey (Royal Decree No. 1421, June 15, 1873) (Pantaloni, 2014). However, significant progress was made only after Giordano’s appointment as Director in 1877, following his return from a world tour (1872–1875). Under his leadership, surveys were initiated in Sicily, the Island of Elba, the Campagna Romana, and the Western Alps (Ercolani, 2017; Pantaloni et al., 2017). These efforts culminated, among other achievements, in the publication of the Geological Map of the Western Alps at a scale of 1:400,000. (R. Ufficio Geologico, 1908; Mosca & Fioraso, 2017).

The development of the geological map of Italy progressed, but the framework established by Royal Decree No. 1421 faced significant criticism.

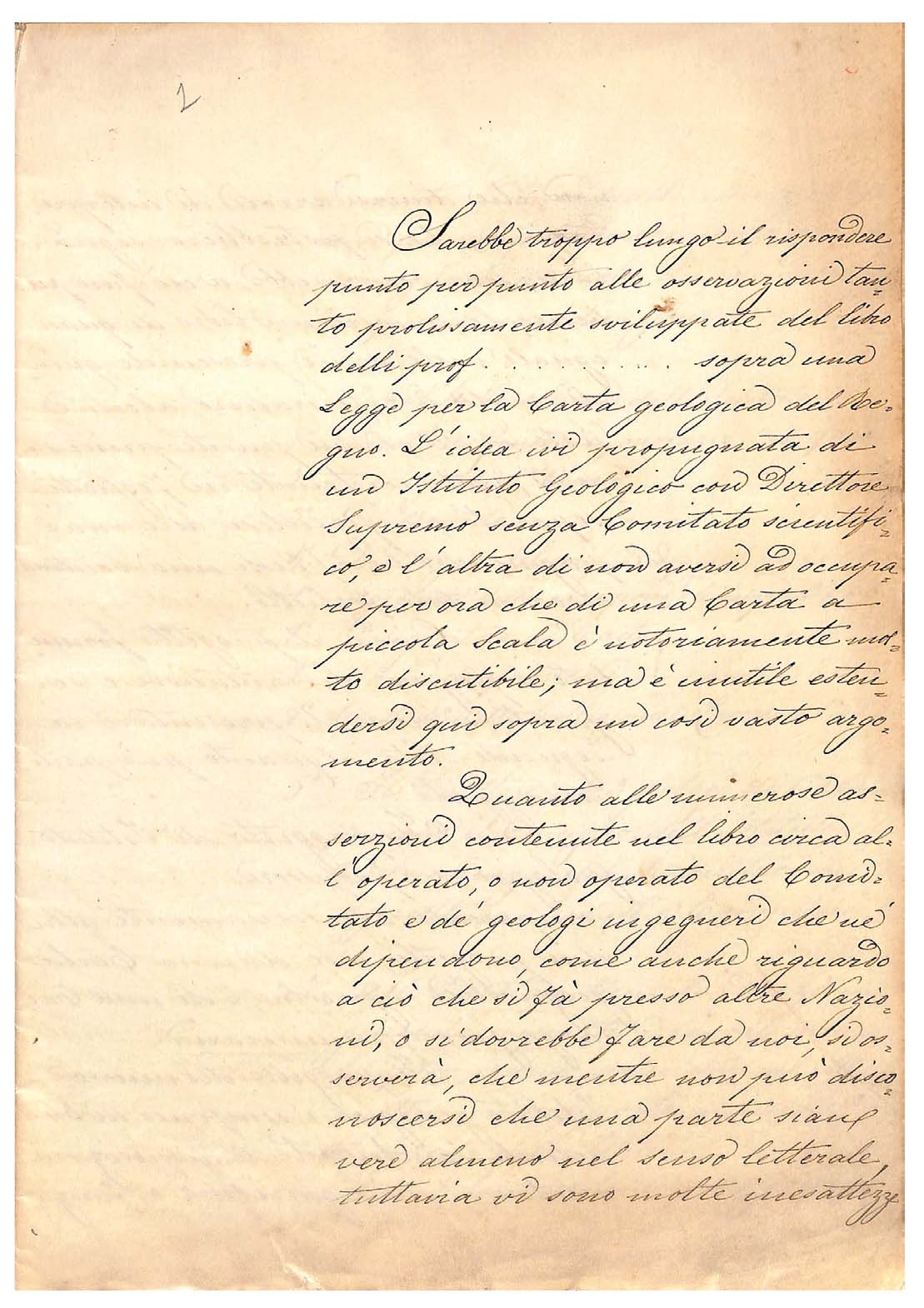

In 1881, the government established a commission comprising leading Italian geologists to evaluate the geological mapping project. The commission reviewed a proposal presented in 1860 by Felice Giordano (Giordano, 1881; Corsi, 2003), which envisioned the geological map being produced exclusively by mining engineers without collaboration from external university specialists. Giordano also suggested publishing the map at a 1:50,000 scale, with an estimated completion time of 26 years and a budget of 5,200,000 Italian Liras, approximately equivalent to 25 million Euros today. Stoppani and Taramelli opposed Giordano’s project but found little support for their objections (Ercolani, 2017; Scoth et al., 2024). Nevertheless, Sella invited them to present an alternative proposal (Fig. 6), where they revived the idea of establishing an autonomous Geological Institute (Stoppani & Taramelli, 1880; Magnani et al., 2011).

- The first page of the original manuscript of the counterproposal for the Geological Map of Italy suggested by Stoppani and Taramelli. Courtesy ISPRA Library-Archive.

After long reflections, the Commission drew up a final report to be presented to the Board, a sort of compromise in which, however, many of the proposals of Stoppani and Taramelli were accepted. In particular, the establishment of an autonomous geological institute was approved, in which engineers and geologists would be on the same level. However, the proposal did not materialise due to lack of funds and only in 1909, 18 years after the Stoppani’s death, Taramelli obtained that external geologists, belonging to the academic staff, could collaborate with the Royal Geological Office (Regio Comitato Geologico, 1909). Finally, with the Royal Decree of 1920 some of the modifications requested by Stoppani and Taramelli were accepted.

This discussion highlights Stoppani and Taramelli’s emphasis on the requisite skills and responsibilities of geologists. They underscored the critical importance of a strong foundational understanding of rock formations and natural geological processes, coupled with proficient field observation and mapping abilities. There was a significant conflict between those who favoured a purely practical, engineering-driven approach (emphasised by the Corps of Mines) and those who advocated for a more scientifically rigorous approach championed by Stoppani and Taramelli. It is undeniable that the specialised training of the Corps of Mining Engineers equaled, if not surpassed, that of the geologists championed by Stoppani and Taramelli. This transformed the debate into a deeply polemical and divisive clash of authority.

The conflict between mining engineers and geologists epitomised a power struggle that heavily influenced the production of the Geological Map (Corsi, 2003, 2007). Despite their differing approaches, both groups shared a common goal of advancing geological knowledge. This tension highlights the enduring challenge of balancing the practical demands of society with the pursuit of fundamental scientific understanding. Ultimately, this debate underscored the importance of scientific rigor, the integration of academic expertise, and a dual focus on research and application, principles that now define modern geological surveys.

The Stoppani’s contribution on glaciation

During the late 19th century (1870s-1880s), Stoppani (1871, 1873a, 1874, 1875) published several works advocating for extensive Alpine glaciation to effectively plunge into the Pliocene sea with a deposition of moraine in marine environment, a hypothesis that met with considerable controversy.

This hypothesis originated from observations made by Luigi Bruno (1877) in a quarry near Bernate Ticino, at the Lombardy-Piedmont border. Bruno, commissioned by Gastaldi for the Royal Geological Committee, conducted geological mapping of Piemonte and Aosta Valley, including the Ivrea moraine amphitheatre (Campanino & Polino, 1999; Dal Piaz, 2013). Stoppani interpreted a deposit of sand and pebbles containing marine shells and erratics as evidence of a Pliocene submarine moraine (Stoppani, 1877, 1880). Stoppani further substantiated this hypothesis through his own observations at Balerna, northwest of Como. He noted the presence of striated pebbles within the uppermost meters of the Pliocene blue clay deposits, just before the transition to the unmistakable glacial terrains associated with the Como moraine amphitheater.

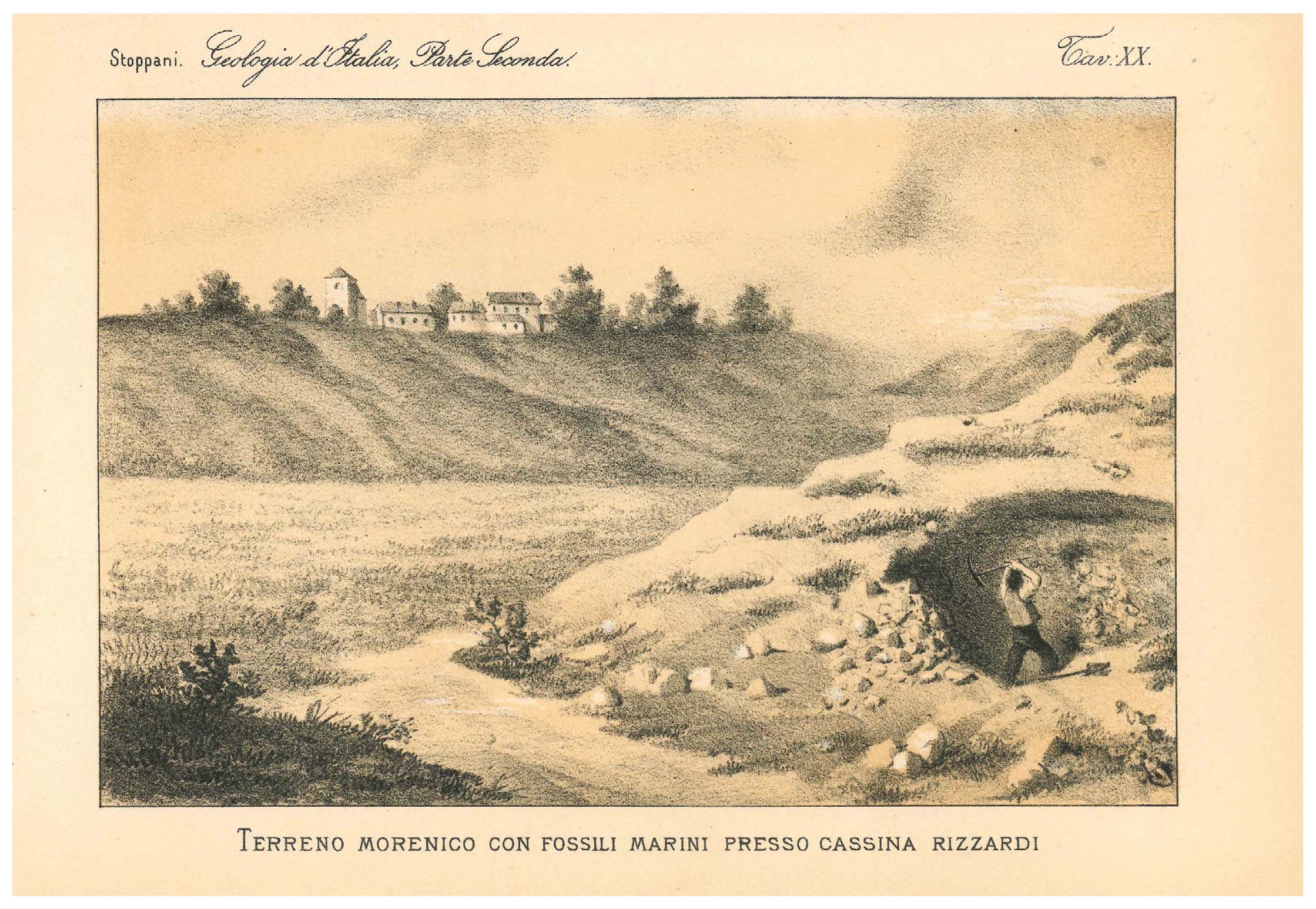

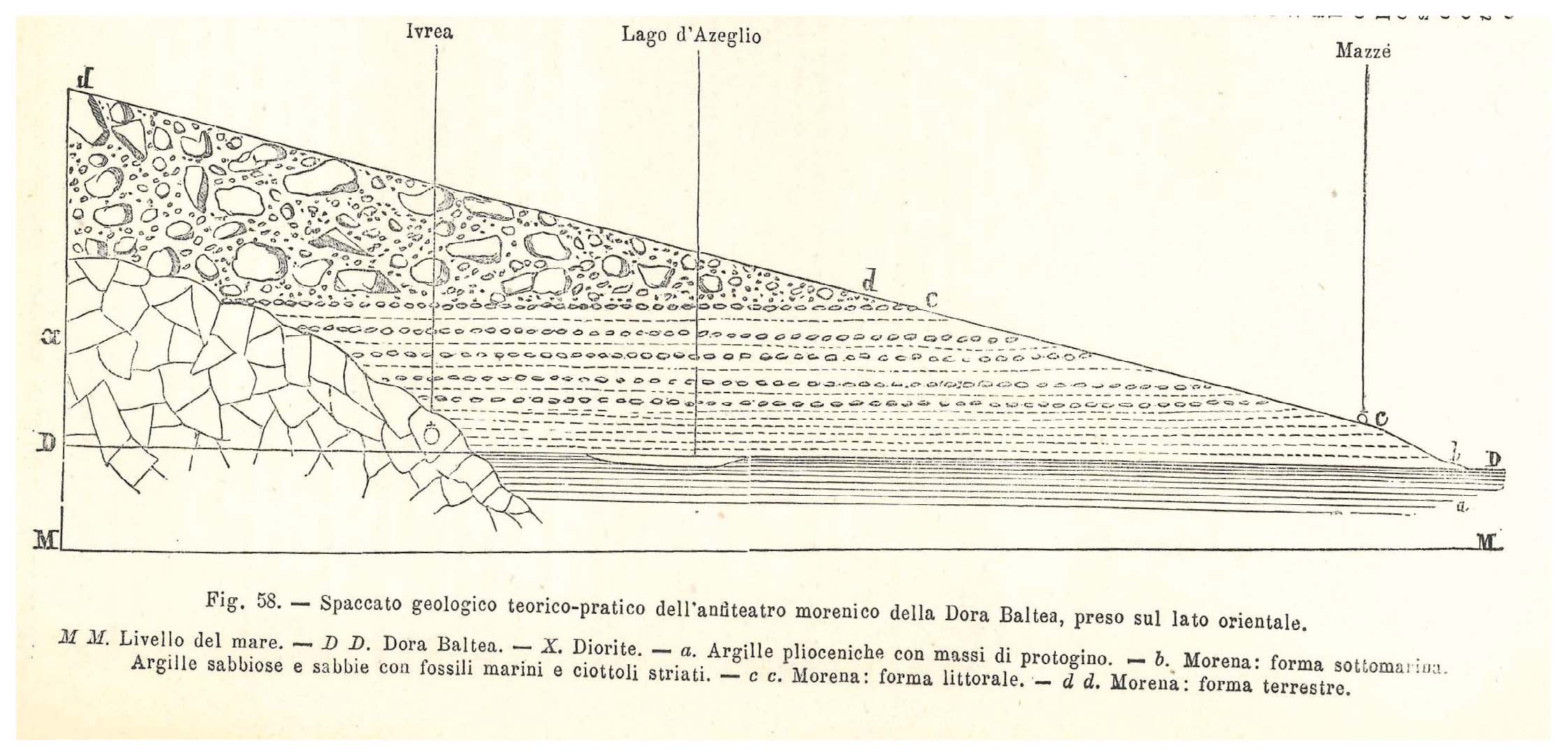

His conclusions state: “The glacial epoch immediately followed the period of the Pliocene blue clays. […] The sea still lapped against the bases of the Alps and Prealps. […] The deposition of the blue clays was not yet complete when the glaciers arrived. […] The result is a marine-glacial deposit scattered with the remains of marine organisms”. Further supporting his theory, Stoppani carried out additional investigations at Cucciago, where he documented the presence of unequivocal marine Pliocene fossils, and at Cassina Rizzardi (Fig. 7), also within the morenic structures in the Como area (Stoppani, 1877). In the same work, Stoppani also attributes a marine-glacial origin to the deposits belonging to the moraine amphitheatres of Lake Maggiore and Dora Baltea (Fig. 8).

- Moraine deposits with fossils near Cassina Rizzardi (from Stoppani, 1877). Courtesy ISPRA Library.

- Theoretical and practical geological cross-section of the Dora Baltea moraine amphitheater, taken from the eastern side. M-M: Sea level; D-D: Dora Baltea river; X: Diorite; a: Pliocene clays with protogine boulders; b: Moraine: submarine form. Clayey sands and sands with marine fossils and striated pebbles; c-c: Moraine: littoral form; d-d: Moraine: terrestrial form (from Stoppani, 1877). Courtesy ISPRA Library.

However, contemporary investigations conducted by Omboni (1876) demonstrated that these deposits represented a reworked assemblage of glacial material and pre-existing Pliocene sediments. Stoppani’s theory of widespread Pliocene glaciation encountered significant opposition from prominent figures within the Italian and international scientific communities, including Desor (1875), Rütimeyer (1875), Favre (1876), Sordelli (1876), and Mercalli (1877).

This issue was revisited in the second half of the 20th century (Carraro et al., 1974), reflecting a renewed interest in the topics raised by Stoppani.

Stoppani synthesised his research in L’Era Neozoica (Stoppani, 1879, 1880) a comprehensive work that explored the glaciation of the Alps and the subsequent evolution of the Italian landscape. He defined the Italian extensive geological history as encompassing the “Cenozoic epoch, the Neozoic epoch, and the Anthropozoic epoch”, starting “with its emergence around the middle of the Eocene and continuing to the present day”.

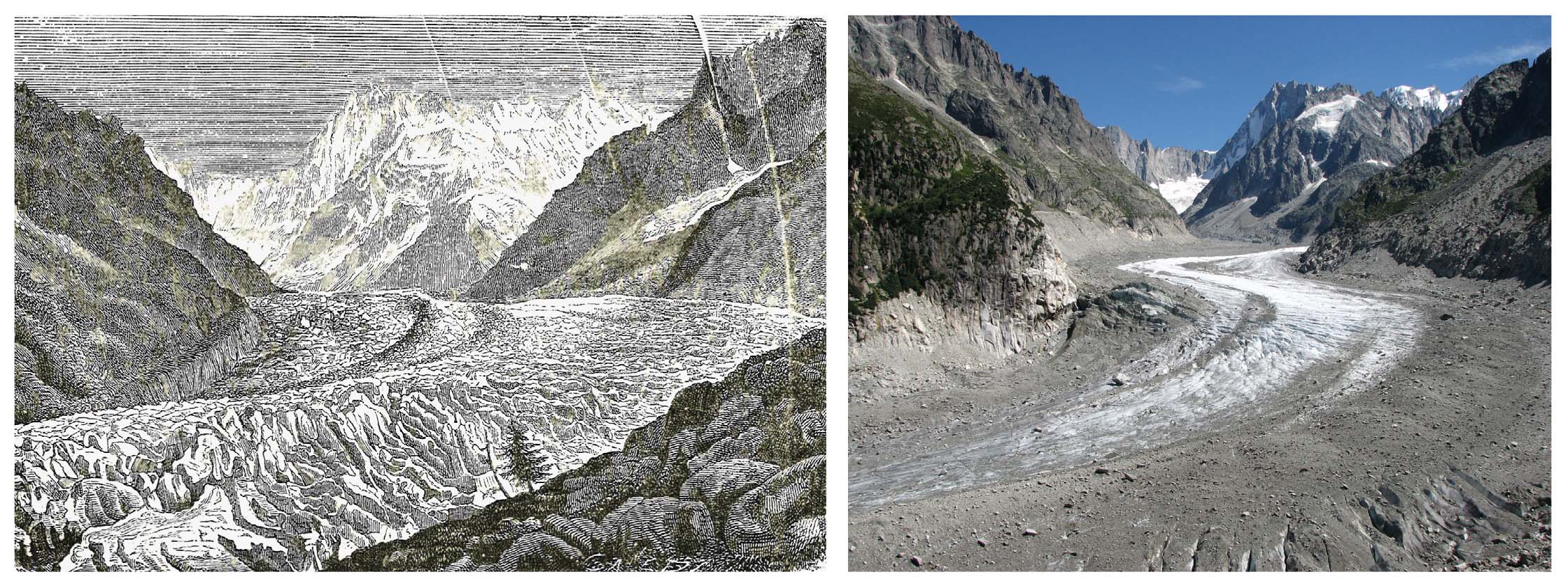

A particularly noteworthy aspect of L’Era Neozoica is its rich iconographic content. The inclusion of illustrations depicting the “Mer de Glace” near Chamonix (Fig. 9) and the medial moraine of the Aar Glacier in the Bernese Alps, among others, provides a visual comparison between the landscapes of Stoppani’s time and the present day. These visual representations significantly enhance the scientific and historical value of the work, documenting the glacial retreat, providing valuable insights into the dynamic interplay between geological processes and landscape evolution.

- On the left: “La Mer de glace a Chamouny” (Stoppani, 1880). Courtesy ISPRA Library. On the right: Mer de Glace, August 6, 2009 (SNappa2006, https://www.flickr.com/people/snappa2006/, CC BY 2.0).

ANTONIO STOPPANI: A PIONEER OF ITALIAN PETROLEUM GEOLOGY

The contribution of Antonio Stoppani to the field of petroleum geology represents a significant side aspect of his professional career. These studies are also crucial for understanding his role as both a patriot and a scientist. In Stoppani’s time, the term “petroleum geology” had a meaning distinct from the one it holds today. This branch of the earth sciences was still in its infancy, and early scientists operated at the crossroads of naturalistic observation, chemical analysis, geological interpretation of petroleum and natural gas seepages, and the study of rudimentary exploitation techniques. The methods for hydrocarbon production at that time were far from being fully industrialised, and the systematic exploitation of natural gas would not begin until the 1930s.

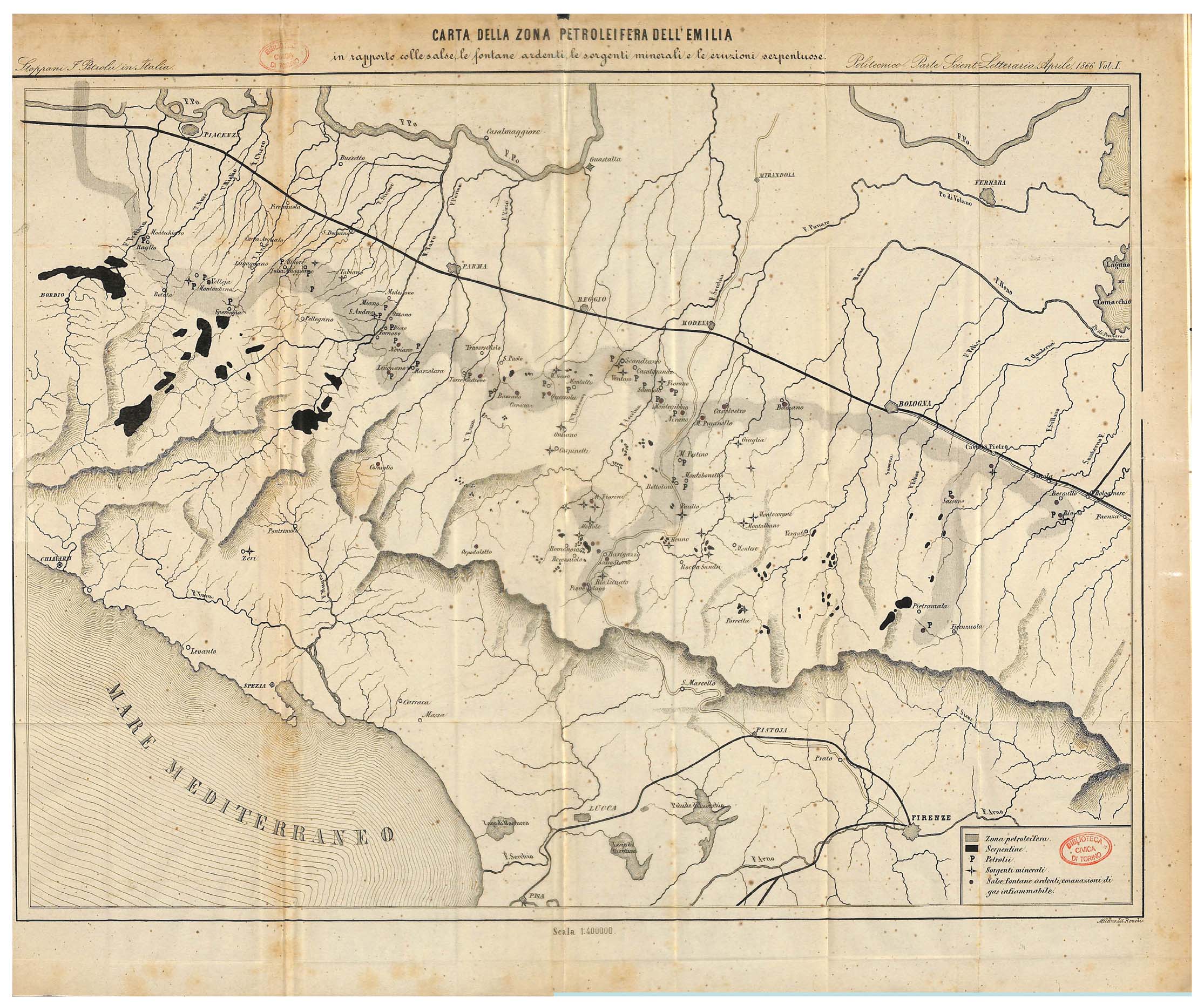

Stoppani’s major works on the subject, including his Saggio di una storia naturale dei petrolii (Stoppani, 1864), were groundbreaking in the field of petroleum exploration in Italy. This long essay provided a comprehensive and innovative analysis of petroleum sciences, framing them within a natural history context. His subsequent writings, such as the Relazione di un’esplorazione geologica di alcuni distretti petroliferi nelle Provincie di Parma e di Piacenza (Stoppani, 1865b) and the Note ad un Corso annuale di Geologia (Stoppani, 1865a), expanded on these ideas, incorporating detailed observations and technical precision. He also published a series of articles in Il Politecnico (one of the first scientific journals in Italy founded in 1839 by Carlo Cattaneo), titled I Petrolii in Italia (Stoppani, 1866). These contributions offered a thorough analysis of petroleum resources across various Italian regions, including Abruzzo, Emilia, and Sicily, accompanied by a map of the petroleum zones of Emilia (Zanoni, 2014; Gerali et al., 2018; Macini et al., 2020, 2022).

These works marked the beginning of scientific research into petroleum geology in Italy, coming just a few years after the first industrial petroleum discovery in the United States at Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. At that time, hydrocarbons were primarily used as raw materials for civil and industrial lighting, and Stoppani referred to them as “the hydrocarbons, or luminous compounds of hydrogen and carbon” emphasising their utility and geologic significance.

In his writings, Stoppani displayed a remarkable ability to contextualise petroleum within broader geological frameworks. He analyzed the origin of petroleum, its ecological implications, and its environmental sustainability - a visionary approach that anticipated debates occurring only decades later. He suggests and discusses a possible dual origin of petroleum substances, attributing it both to volcanic activity, involving distillation and fermentation processes, and to organic phenomena, although he considered the latter less influential. He wrote: “I admit first of all as indubitable that the production of mineral hydrocarbons is related to volcanic activity. […] The generation of petroleum is also a volcanic phenomenon, and that petroleum is a volcanic product, like any other volcanic mineral, independently of any organic substance” (Stoppani, 1864, p. 39).

Stoppani’s deep engagement with contemporary geological literature is evident in his references to American scholar Thomas Sterry Hunt (Duchesne, 2003), whose studies anticipated anticlinal tectonics (Sterry Hunt, 1865). His intellectual exchanges with figures like Marcelin Berthelot further underscore his prominent role in the scientific community of his time (Stoppani, 1864, 1865a).

Stoppani’s involvement in petroleum studies extended beyond academic pursuits. He visited oilfields in Emilia, Abruzzo, and Lazio, documenting the close association of crude oil, salt water, and natural gas in petroleum reservoirs (Gerali et al., 2018). Alongside Giovanni Capellini, he was recognised as a leading expert in the Italian petroleum industry and served as a consultant for companies active in these regions. In 1866, he published a topographic map of the petroleum zones in Emilia (Fig. 10), which would later be plagiarised by Edward John Fairman in 1868 without acknowledgment (Macini et al., 2022).

- Map of the petroleum zones of Emilia. Gray shaded areas indicate the geologic trend of petroleum zones and black spots are the principal outcrops of ophiolitic rocks. The map also locates oil springs, active oil wells, mineral springs, mud volcanoes, and gas seepages (Stoppani, 1866).

His activity as a consultant in the field of petroleum geology included significant projects such as his geological studies in Abruzzo, commissioned by Italian entrepreneurs in 1864, and his assessments of the petroleum potential in Parma and Piacenza for American businessmen William Mayo and Vincenzo Botta between 1864 and 1866. Despite his warnings about the challenges posed by the geological diversity of the Italian fields compared to American ones, he advocated for the introduction of modern drilling technologies to overcome these obstacles.

Stoppani’s commitment to linking geology with industrial development is evident in his writings. In the 1864 Saggio di una storia naturale dei petrolii, he emphasised the role of geology in identifying promising areas for exploration, even in the absence of visible oil seepages. He argued for the application of stratigraphic geology to industry, highlighting its potential to contribute significantly to Italy’s economic development.

Later in his career, Stoppani was appointed as the scientific director of the petroleum field of San Giovanni Incarico, a site that became central to Italian petroleum production (Macini et al., 2024). His detailed observations of oil wells, such as those in Miano di Medesano, near Parma, combined vivid descriptions with technical insights. However, by 1881, disillusioned by the profit-driven focus of his associates and the lack of commitment to scientific and social advancement, he sold his shares in the Società delle Miniere Petroleifere and withdrew from petroleum-related activities.

Despite this, Stoppani’s legacy in petroleum geology remains significant. His pioneering studies, theoretical contributions, and practical involvement laid the foundation for modern approaches to the field, reflecting his profound understanding of both scientific principles and their industrial applications. His works continue to witness the transformative potential of integrating geology with technology and society progress (Macini et al., 2020).

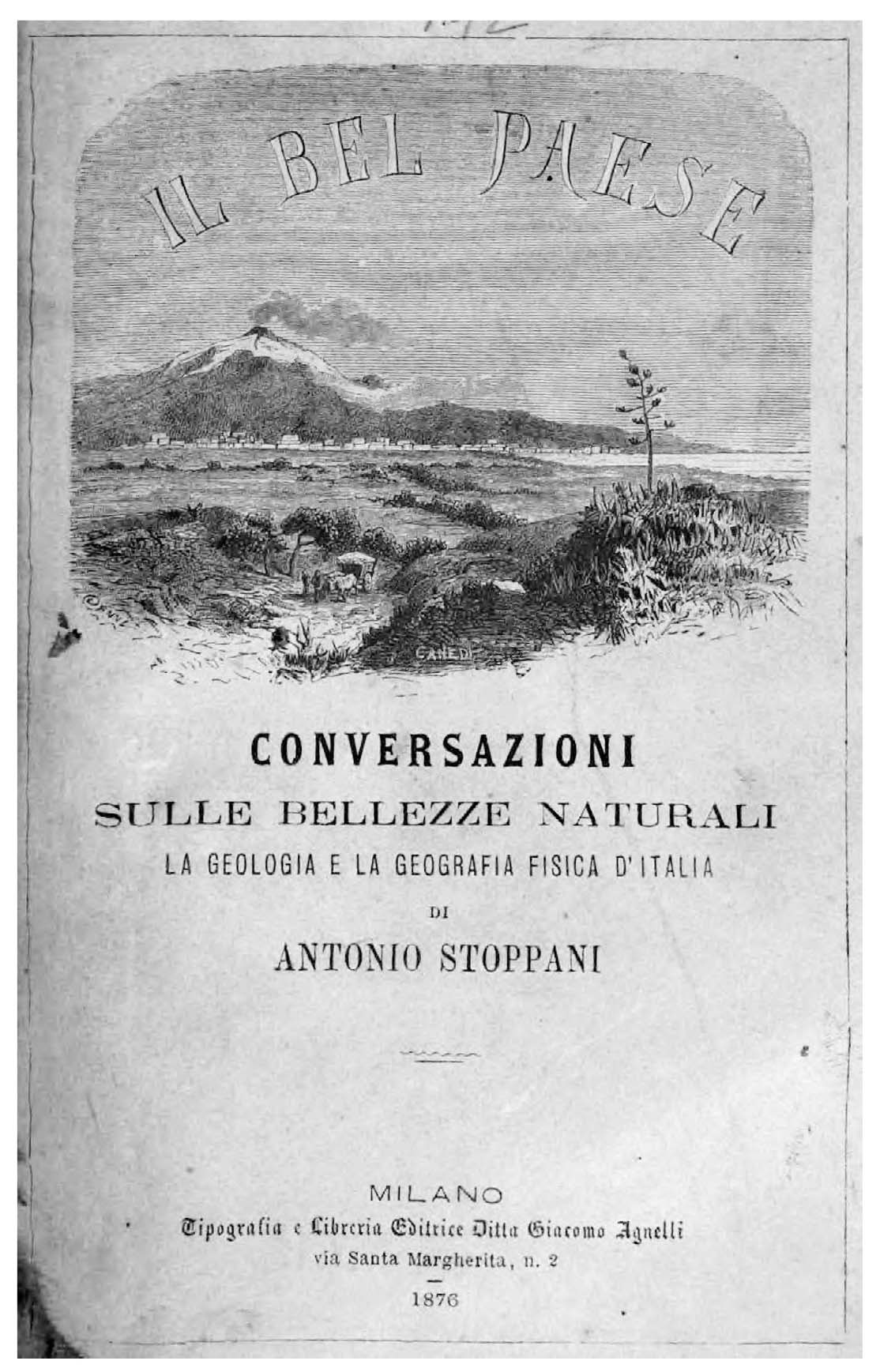

IL BEL PAESE: A LANDMARK IN ITALIAN SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION

Stoppani’s most celebrated work, Il Bel Paese (a title still fueled by an enduring spirit of Italian unification), represents a milestone in the popularisation of geological and natural sciences. The book (Stoppani, 1876) has a revealing subtitle, “Conversations on the natural beauties, geology and physical geography of Italy”. Initially disseminated through children’s magazines and the periodical Adolescenza under the column Serate con lo zio, the book skillfully blended naturalistic observation with accessible language, making many geological concepts more comprehensible to a broad audience (Fig. 11).

- Book cover of the first edition of Il Bel Paese (1876); the drawing, made by the famous engraver Francesco Canedi, depicts Mount Etna seen from Catania. Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82416359.

Il Bel Paese meticulously documents Stoppani’s extensive fieldwork across the Italian peninsula, and is presented as an idealised journey from the Alps to Sicily. This narrative explored the diverse geological formations, minerals, flora, and fauna. Beyond its scientific contributions, the work fostered a heightened sense of national identity among Italians, a fact recognised by prominent writers and historians of science (Redondi, 2012).

The enduring popularity of Il Bel Paese is evident in the widespread adoption of its title, inspired by Dante Alighieri and Francesco Petrarca, emphasising the unique beauty and features of the Italian landscape. Petrarca (Canzoniere, 146) defines Italy as il bel Paese ch’Appennin parte, e ’l mar circonda et l’Alpe (the beautiful Country that is divided by the Apennines, and surrounded by the sea and the Alps), while Dante (Inferno, XXXIII, 80) identify Italy as the bel paese là dove ‘l sì suona (the beautiful Country where “si” sounds for yes). The book’s success can be attributed to its innovative approach, seamlessly integrating traditional knowledge with emerging industrial and scientific advancements within a unified pedagogical framework.

Through 32 engaging scientific conversations written in accessible prose, Il Bel Paese introduced the public to a wide range of natural science concepts, particularly focusing on geological curiosities and the aesthetic appeal of the Italian landscape. The book’s impact was profound, reaching 120 editions by 1920 and subsequently adopted as a school textbook.

Stoppani’s introduction to natural history emphasised the inextricable link between humanity and the natural world, asserting “man must never disappear from nature, nor must nature disappear from man.” While rooted in 19th-century positivist thought, some of Stoppani’s views, such as his anthropocentric “anthropozoic” concept, may diverge from contemporary ecological perspectives. However, Il Bel Paese should not be solely judged by modern standards. Instead, its enduring value lies in its advocacy for a non-localistic and non-commercial appreciation of the land, its successful synthesis of scientific and humanistic knowledge, and its emphasis on the crucial role of education in fostering civic engagement.

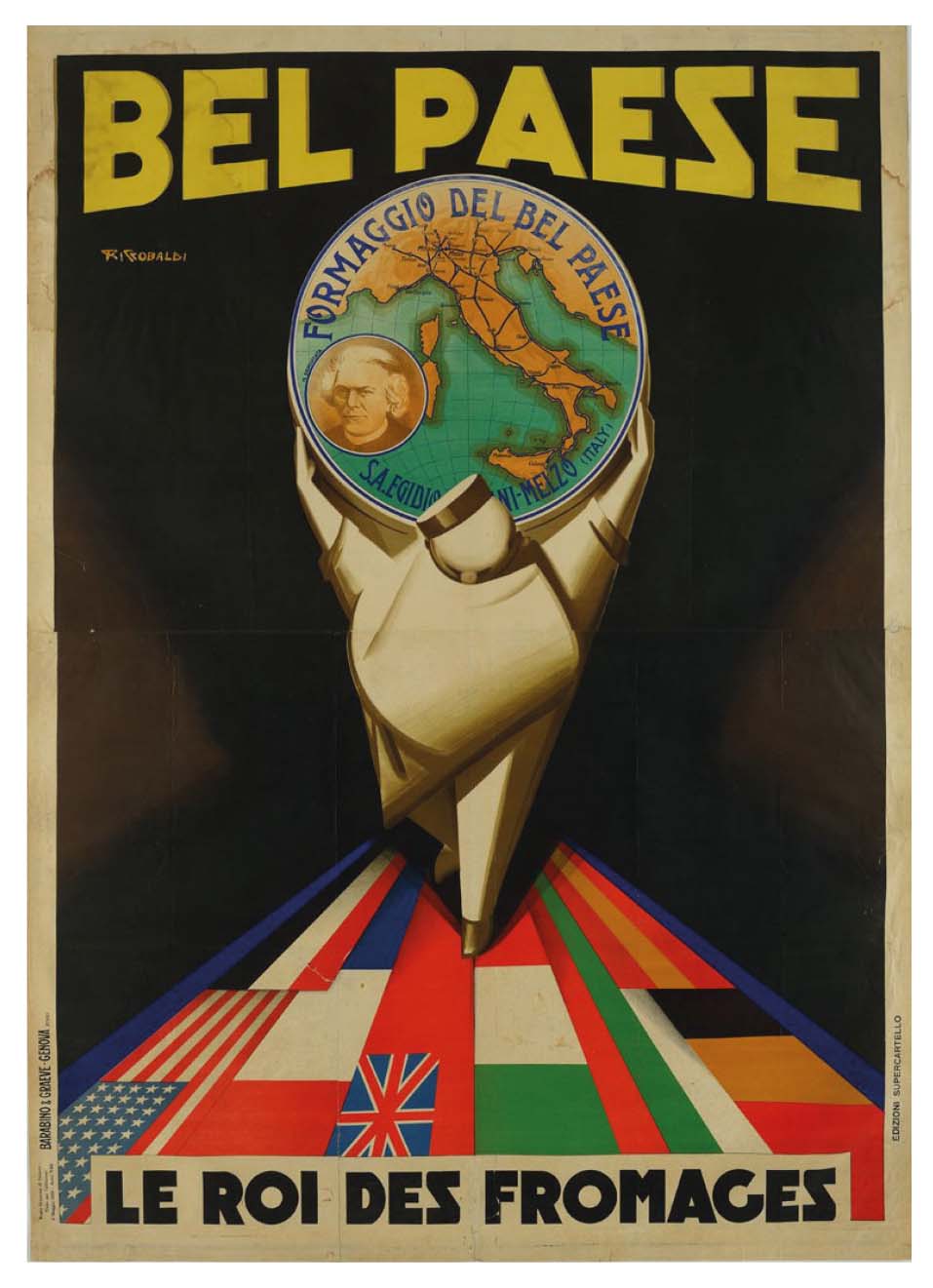

In 1906 Stoppani’s widespread recognition led to the naming of one of the first luxury and renowned Italian industrial cheeses, Bel Paese, after his celebrated book. The cheese packaging prominently features Stoppani’s portrait, and its marketing campaigns throughout the 20th century, featuring artwork by renowned illustrators like Giuseppe Riccobaldi Del Bava (Fig. 12), R.F. Quillio, Raymond Savignac, and Alain Gauthier, further solidified its connection to Stoppani’s legacy.

- A stylized delivery boy walks on a carpet of flags carrying on his shoulder a wheel of Bel Paese, “the king of cheeses”. The round cheese label displays a map of the main Italian railways of the early 20th century and the classic portrait of Stoppani normally used in the frontispiece of his best seller. Advertising poster by Giuseppe Riccobaldi Del Bava, before 1930. Public domain, https://catalogo.beniculturali.it/detail/HistoricOrArtisticProperty/0500674613.

BEYOND “IL BEL PAESE”: STOPPANI’S BROADER SCIENTIFIC CONTRIBUTIONS

While Il Bel Paese remains Stoppani’s most renowned work, it overshadows other significant contributions to scientific thought. Acqua ed Aria ossia la purezza del mare e dell’atmosfera fin dai primordi del mondo animato (Stoppani, 1882) exemplifies the seamless integration of Stoppani’s scientific and philosophical perspectives, reflecting the themes explored in his lectures at the Salone dei Giardini Pubblici in Milan, organised by Emilio Cornalia in 1873 (Zanoni, 2014).

In Acqua ed Aria, Stoppani delves into the intricate relationship between water and air, examining them from both geological and ecological perspectives. He emphasises their crucial roles in maintaining the delicate balance of life on Earth, introducing a proto-ecological concept of the “economy of nature” – a cyclical system that continuously replenishes itself, preventing a back turn into primordial chaos (Zanoni, 2010).

Stoppani’s reflections on humanity’s place within the natural world offer intriguing insights. While he asserts “the Earth without humanity has no meaning”, highlighting the significance of human presence, he also acknowledges humanity’s potential for deep environmental alterations, labeling it “the thief of the world” in L’uomo e il suo impero sulla Terra (Stoppani, 1873c). This poignant observation foreshadows many of the concerns of modern conservation biology and sustainability concepts.

STOPPANI’S LATE CAREER: RECONCILING FAITH AND SCIENCE

Following the journey documented in Da Milano a Damasco. Ricordo di una carovana milanese nel 1874 (From Milan to Damascus. Memories of a Milanese expedition in 1874; Stoppani, 1888), he returned to his academic pursuits. In this travelogue, he illustrates various aspects of an unfortunate journey to the Holy Land through the Near East, carried out together with a party of eight priests and a nobleman, all from Milan. In Damascus, Stoppani broke his leg in an accident while riding a horse (only by chance it did not prove fatal, and he managed to survive), and remained there for over a month, before taking a daring journey back to Italy, without visiting Jerusalem. Written in a colloquial language very close to that used in Il Bel Paese, he portraits the landscape, with a keen eye to geology, physical geography, history, climate, and in some passages, religion, underlining the complex issues of daily coexistence with other faiths (Muslims, Jews, Orthodox, Protestant churches, etc.). It is the travelogue of a Western man of the 19th century, who was a mature scientist, but also a Catholic priest, albeit from the less conservative wing of the clergy.

The 1870’s was a decade full of considerable intellectual and theological turbulence for Stoppani (Cornelio, 1898; Zanoni, 2014). He faced mounting pressure from conservative Catholic parties who sought to reignite the Rosminian controversy. This controversy had been temporarily reconciled by Pope Pius IX’s Dimittantur, a decree issued by the Congregazione dell’Indice in July 1854, which formally exonerated the works of Antonio Rosmini from accusations of heresy and error.

In the 1880’s, influenced by his interactions with renowned scientists such as Eduard Suess (Stoppani met Suess personally in 1866-67), he embarked on a period of intellectual exploration, integrating his early studies in religious philosophy with apologetic and exegetical research. Although he was not influenced by the mobilist revolution theorised by Suess (Dal Piaz & Dal Piaz, 1982) and remained closely linked to fissist models, this period culminated in the publication of several articles exploring the intricate relationship between science and faith, and examining the interplay between the modern world and the Catholic Church. Notably, he penned Il Dogma e le scienze positive (Stoppani, 1884), a significant essay that delved into these complex issues (Bruni, 1886).

HIS FINAL WORK: EXEMERON

The pontificate of Pope Leo XIII ushered in a period of renewed engagement between the Catholic Church and contemporary society. This intellectual climate provided a fertile ground for Stoppani’s continued intellectual pursuits. He dedicated himself to drafting his late work, Exemeron, subtitled “New essay of an exegesis of the history of Creation according to reason and faith”, a profound commentary on Genesis 1 narrative (hence Exemeron, six days). “I have already stated elsewhere that the geological and cosmological studies, in which I have already spent the greater part of my life, I have not directed only to the acquisition of natural truths, from which human science draws all its nourishment, indeed its being; but I have also turned them with love to the conquest of supernatural truth, and specifically to the understanding of certain points of Sacred Scripture, which seemed to me at first to really need to acquire light from profane studies” (Stoppani, 1893).

In Exemeron, Stoppani expressed his deep concern about the prevailing trend among some apologists to adopt a concordist approach to reconciling faith and science. He argued that such attempts to force an artificial harmony between religious doctrine and scientific findings were ultimately misguided and potentially detrimental to both. Instead, he advocated for a more nuanced and nuanced approach that recognised the distinct domains of faith and reason.

Beyond his scholarly pursuits, Stoppani devoted considerable effort to promoting scientific literacy among clergy and laymen alike. He believed that a deeper understanding of scientific principles was essential for fostering a more informed and engaged dialogue between faith and reason in the modern world.

THE LEGACY OF ANTONIO STOPPANI

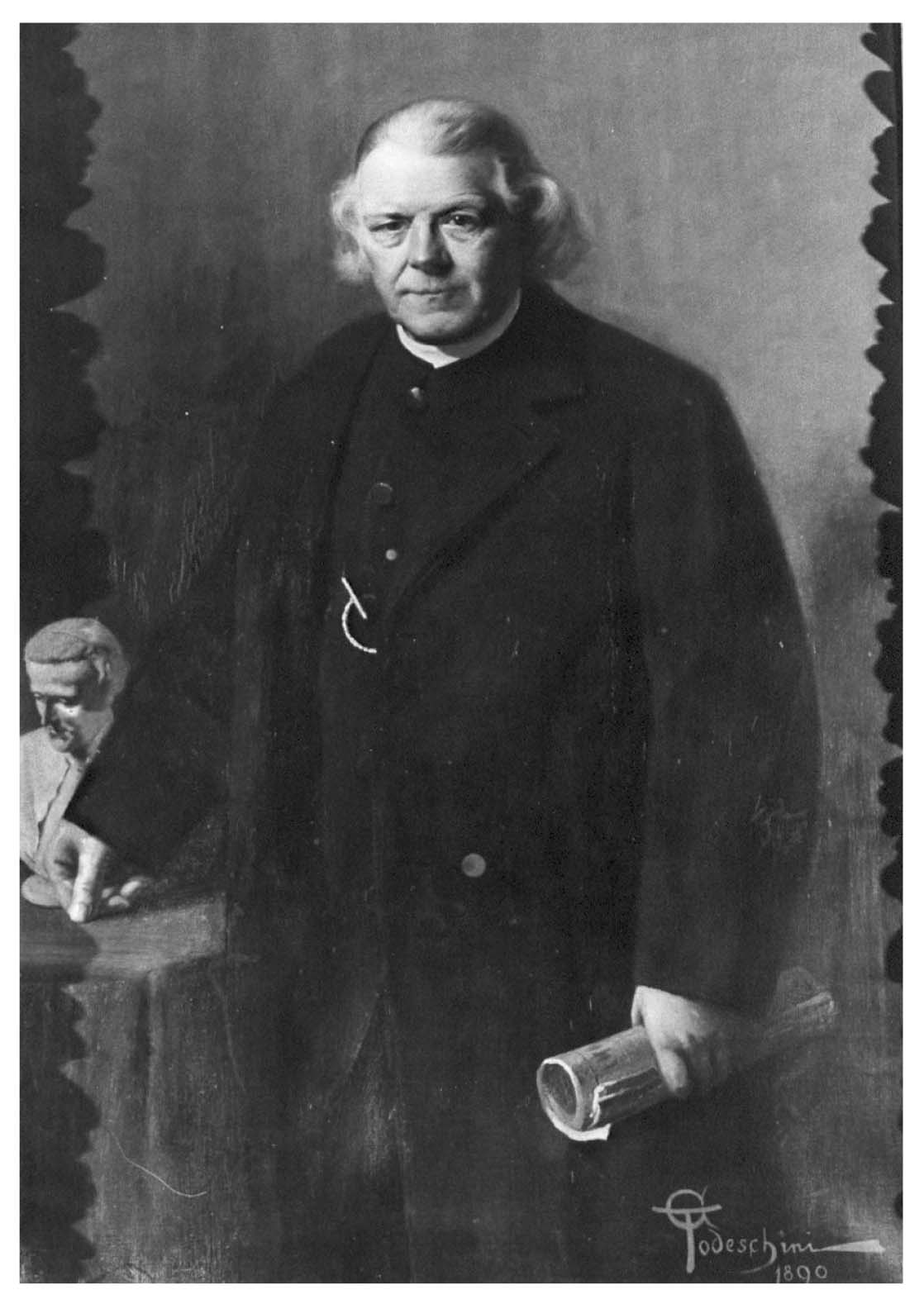

Antonio Stoppani’s death in Lecco on January 1, 1891, marked the end of an extraordinary life dedicated to disseminating the advancing scientific knowledge and fostering a deeper understanding of the natural world (Fig. 13).

- Portrait of Antonio Stoppani painted by the nephew Giovanni Battista Todeschini one year before his death. Stoppani wears a black cassock with a watch chain on his chest; he holds a newspaper in his left hand and leans his right hand on a table on which is a sculpture of Antonio Rosmini (Musei Civici di Lecco, https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/opere-arte/schede/G1050-00204/).

Beyond his groundbreaking contributions to geology and palaeontology, Stoppani emerged as a prominent figure in science communication and as an outstanding and prolific writer. He recognised the vital role of disseminating scientific knowledge to the broader public, believing that scientific understanding was crucial for building a modern and informed society. His efforts to make complex scientific concepts accessible to a wider audience through engaging narratives and accessible language set a precedent for science communication in Italy (Redondi, 2012; Pantaloni et al., 2024).

Significantly, Stoppani’s writings, using his own term era antropozoica, anticipated the modern concept of the Anthropocene by more than a century. He astutely observed and documented the profound and far-reaching impacts of human activities on the planet’s ecosystems. His insights into the interconnectedness of human actions and environmental consequences provide valuable historical context for contemporary discussions on environmental sustainability and the future of the Anthropocene era.

Stoppani’s enduring legacy lies in his ambitious attempt to elevate Italian geology to a leading position on the international scientific stage. Through his multidisciplinary and encyclopedic approach, and his rejection of narrow specialisation - evident in the breadth of his work - he stands out as a scientist of considerable national significance. However, despite his efforts, he was unable to fully achieve this goal. Unlike his contemporaries, such as Darwin and Lyell, who embodied the depth of specialised knowledge driving the scientific advancements of the time, Stoppani’s generalist approach, though admirable, lacked the focused expertise necessary to place him at the forefront of the rapidly evolving scientific landscape.

In addition, his later work reflects his commitment to reconciling science and faith, exploring the intricate relationship between these two domains. While he made a genuine effort to bridge the divide, his lack of deep specialisation may have hindered his ability to address the complexities of this challenge in a way that resonated widely. Nonetheless, his intellectual breadth and his pursuit of harmony between science and spirituality remain a testament to his vision and continue to inspire within Italian culture and beyond.