INTRODUCTION

The history of geothermal exploration in Italy and use of geothermal fluids is largely dominated by the studies around the natural manifestations of Tuscany (central Italy), in the region that is today known as the Larderello geothermal area (Fig. 1), located in the inner northern Apennines, a former collisional belt (Cretaceous-Early Miocene), now experiencing extensional tectonics (Miocene-Present). Extension is eastward migrating (Molli, 2008; Barchi, 2010), and, since Late Miocene, it has been associated with eastward migrating magmatism (Serri et al., 1993). This latter determined widespread hydrothermal mineralisation, as it is the case of Tuscany (Tanelli, 1983), giving presently rise to active geothermal systems (e.g., Larderello) and thermal springs (Minissale, 2004; Dini et al., 2005), that are located in a regional context where the average heat flux is of about 120 mWm-2 (Della Vedova et al., 2001; Pauselli et al., 2019).

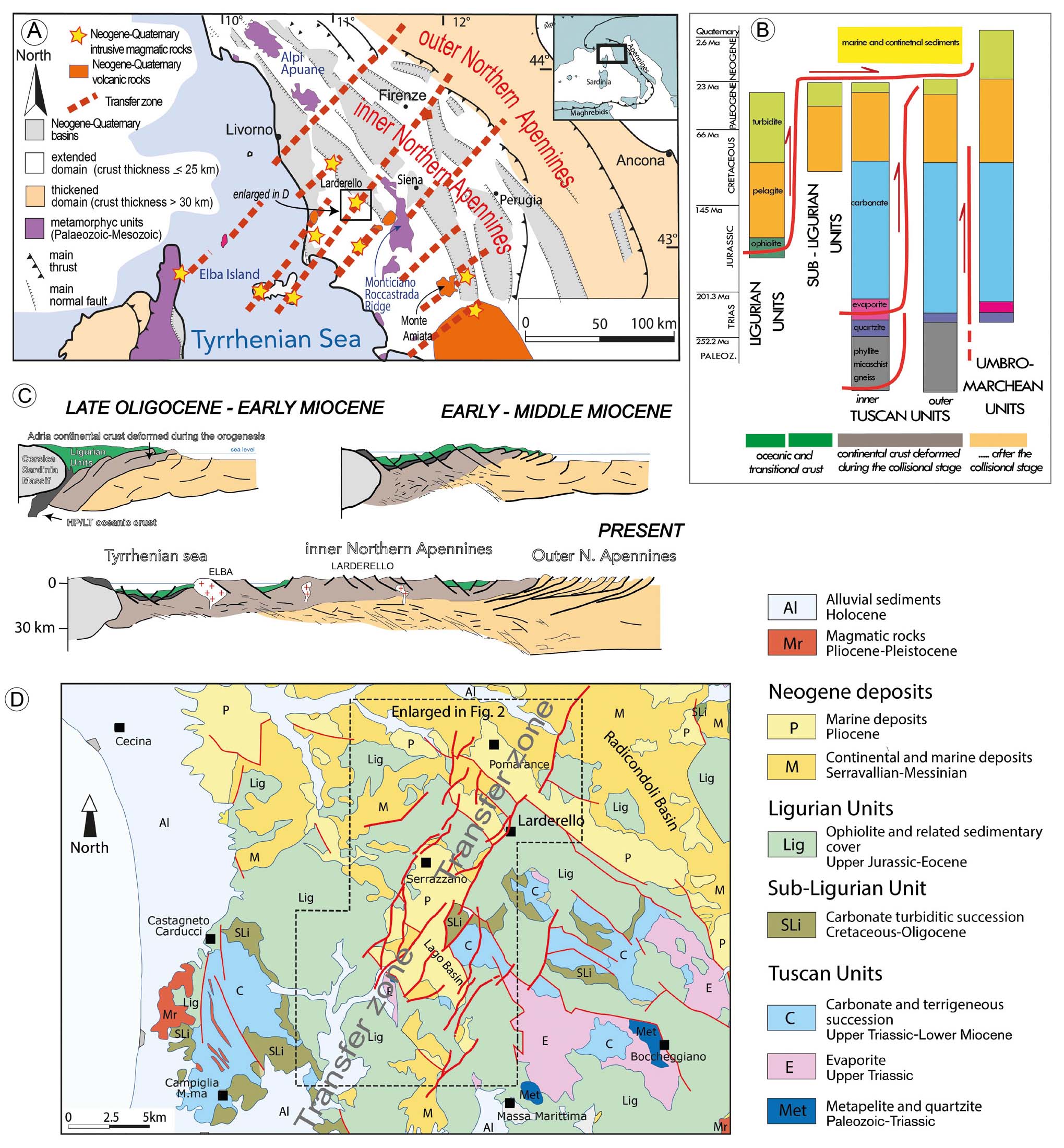

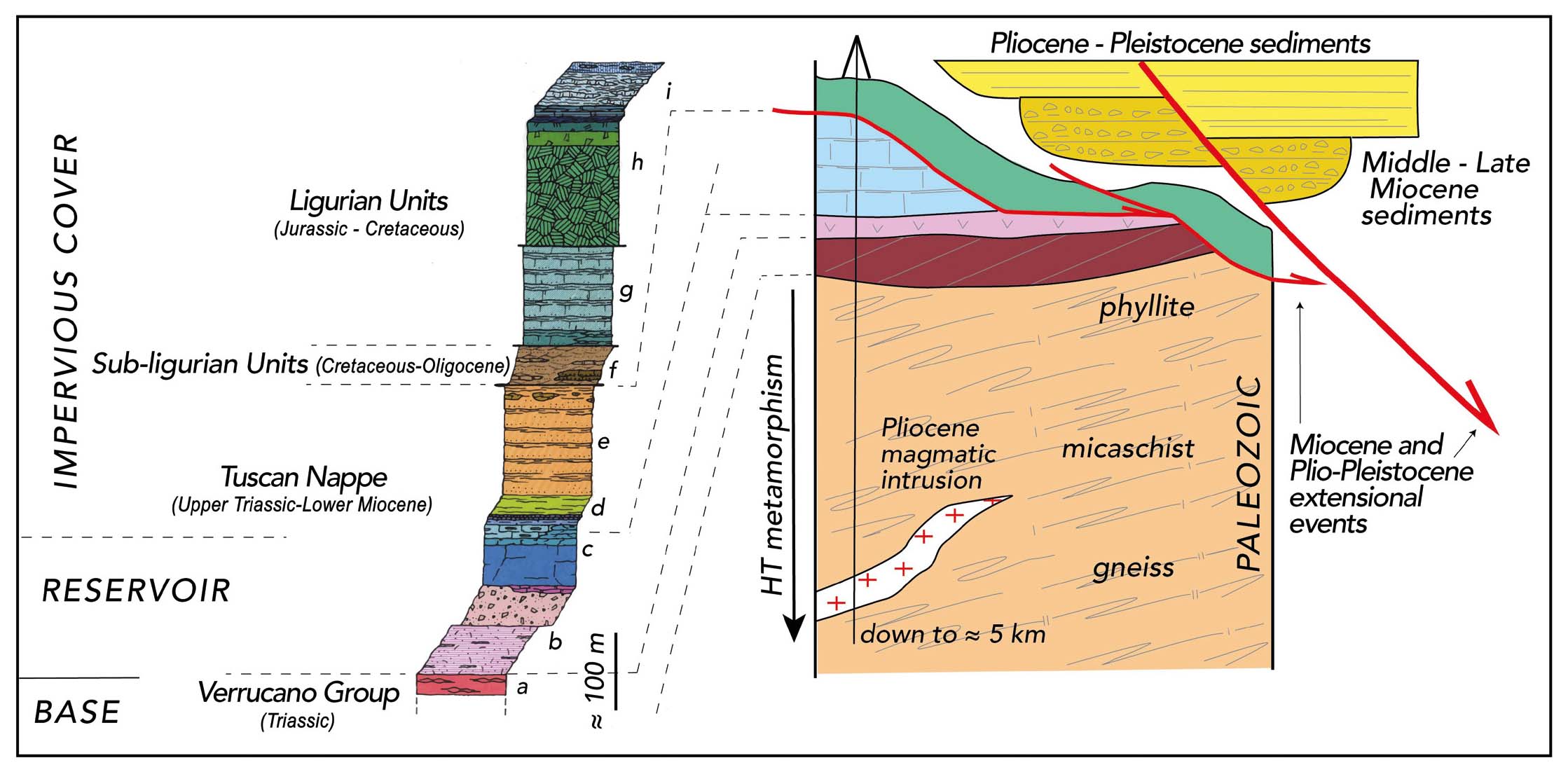

- Structural sketches and geological cross sections illustrating the Northern Apennines evolution. A - structural sketch map illustrating the relationships between the main Pliocene-Pleistocene basins and transfer zones in the inner Northern Apennines, characterised by a 22-24 km thick crust while the outer Apennines by a 35-40 km thick crust (Di Stefano et al., 2011); B - relationship between the different tectono-stratigraphic units of inner northern Apennines and related palaeogeographic domains: These are: (i) the Ligurian Units, composed by remnants of Jurassic oceanic crust, and a Jurassic–Cretaceous mainly clayey cover; (ii) the Subligurian Units made up of Cretaceous–Oligocene arenaceous and calcareous turbidite, related to transitional crust. Ligurian and Subligurian Units were thrust eastwards over the Tuscan Domain during Late Oligocene–Early Miocene times; (iii) the Tuscan Nappe including sedimentary rocks ranging from Upper Triassic evaporite to Jurassic–Cretaceous carbonate and Cretaceous–Lower Miocene marine clastic sediments. During Early Miocene, the Tuscan Nappe, already involved in duplex structures, detached along the Late Triassic evaporite level to thrust over the outer Tuscan Domain and the inner part of the Umbrian–Marchean Domain; (iv) the outer Tuscan Domain gave rise to a metamorphic unit consisting of green-schist metamorphic rocks deriving from a Triassic–Oligocene sedimentary succession, similar to the one characterising the inner Tuscan Domain. The substratum of the Tuscan Domain is composed, from the top, of Triassic quartzite and phyllite (Verrucano Group Auctt.) and Palaeozoic phyllite. At deeper levels, borehole logs describe micaschist and gneiss; (v) Umbro–Marchean Domain consists of continental-margin deposits ranging from Triassic to Upper Miocene; this Domain represents the outer zone of the Northern Apennines, where a fold-and-thrust belt developed during Neogene. C - Schematic geological cross-sections showing the collisional and post-collisional evolution in the northern Apennines. During Miocene, extension determined the lateral segmentation of the stacked tectonic units through low-angle normal faults. This process led the Ligurian Units, the highest units in the orogenic tectonic pile, to overlie the Upper Triassic evaporite and/or the Paleozoic phyllite. From Early Pliocene to Present, high angle normal faults dissected all the previous structures, giving rise to tectonic depressions where Pliocene continental to marine sediments deposited. Younging eastwards magmatism accompanied extension since Middle Miocene, From the Middle Pliocene, southern Tuscany has been affected by surface uplift (after Liotta et al., 2021, modified); D - detail of the study area and its surroundings. The investigated area is indicated by a square and enlarged in Fig. 2 (after Liotta & Brogi, 2020, modified).

The emplacement of magmatic bodies, volcanism and geothermal manifestations have been controlled by NE-trending transfer zones (Dini et al., 2008; Liotta et al., 2015), coeval with the NW-trending normal faults (Fig. 1A). The transfer zone passing through the Larderello area (Figs. 1D-3) includes a Mio-Pliocene basin, interpreted as a pull-apart basin (Liotta & Brogi, 2020) named as the Lago Basin (Lazzarotto, 1967), where the current geothermal production is particularly significant (Gola et al., 2017).

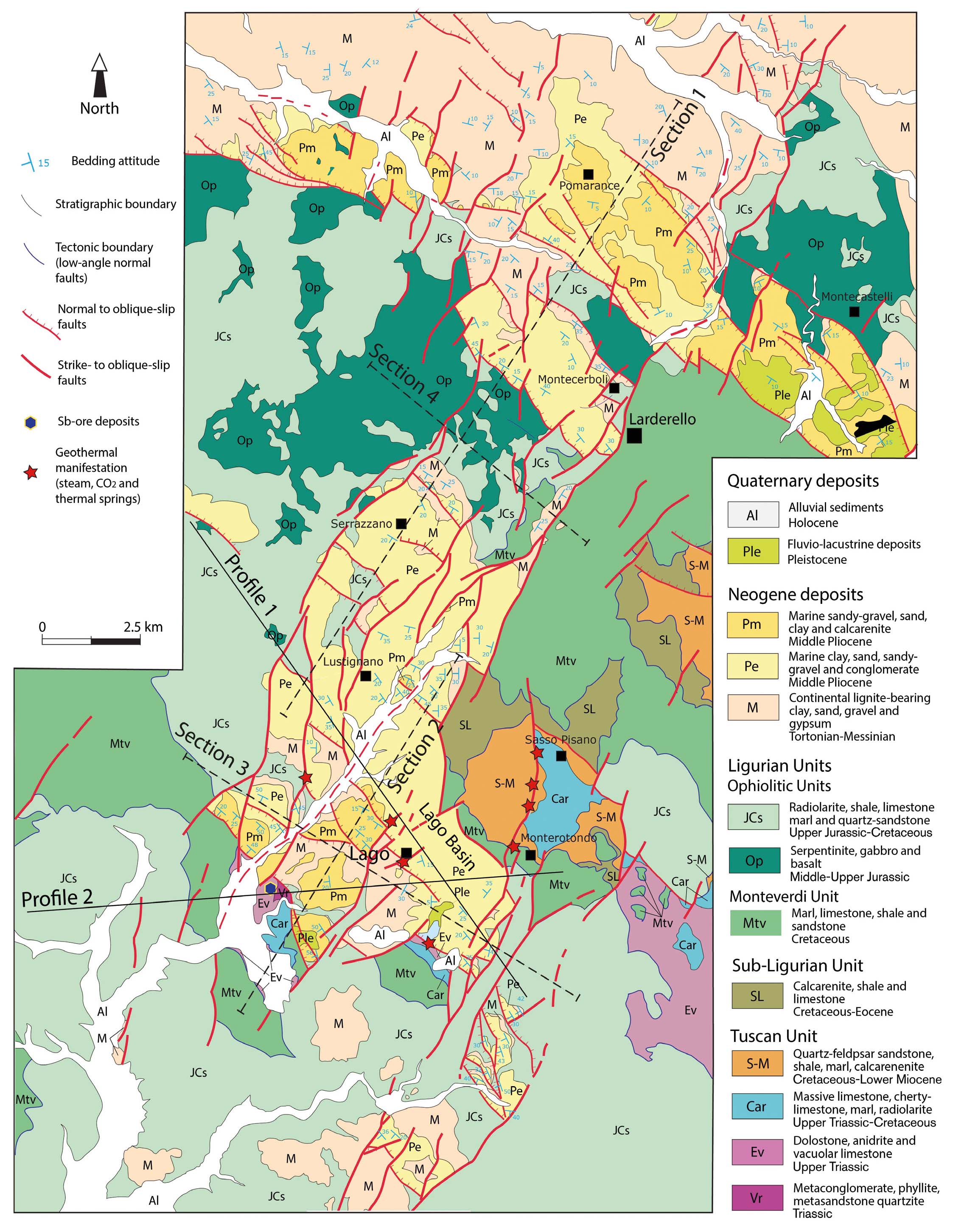

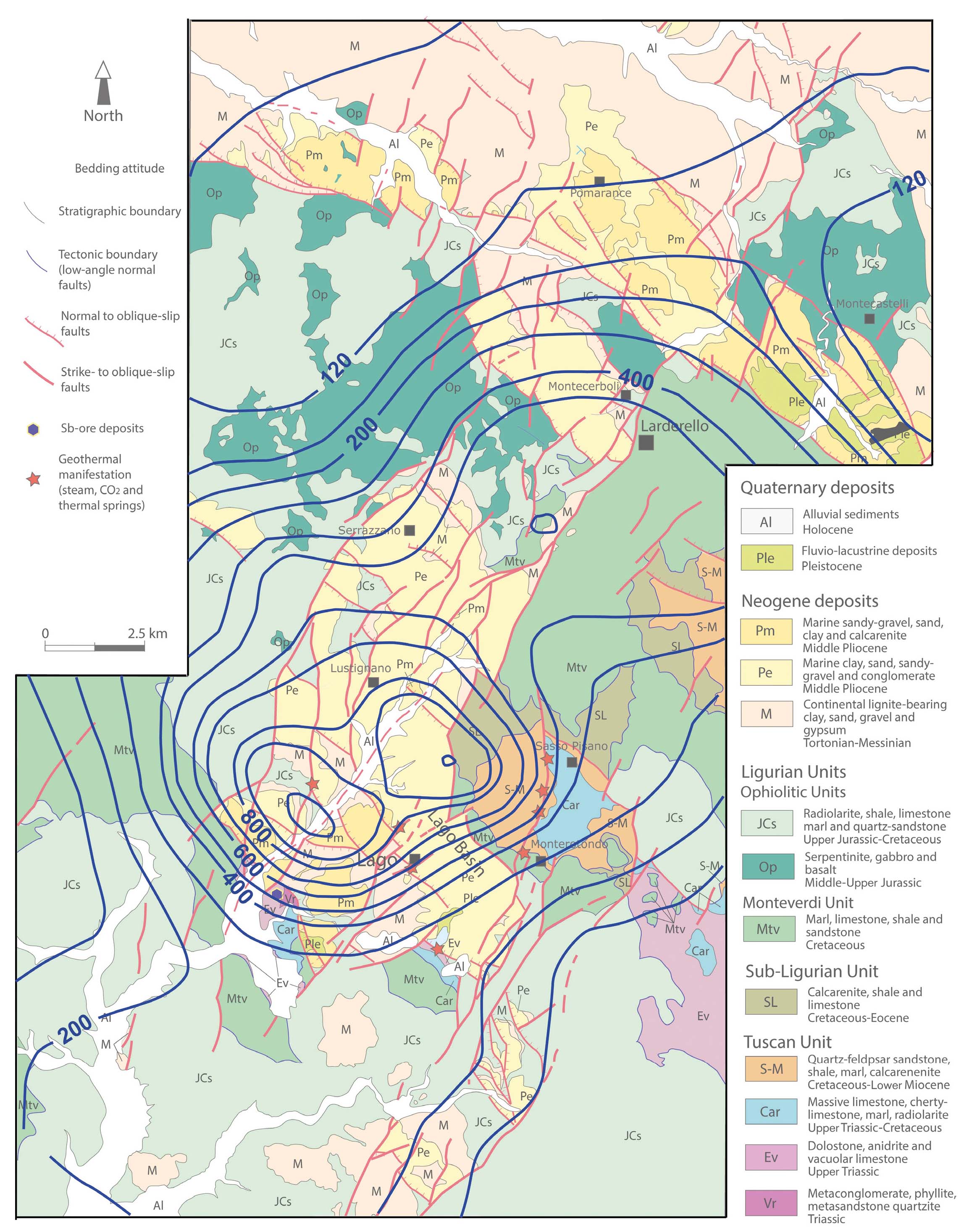

- Geological map of the Larderello and Lago areas with the traces of the geological cross sections and MT-profiles, as shown in Fig. 3 and 10, respectively (after Liotta & Brogi, 2020, modified).

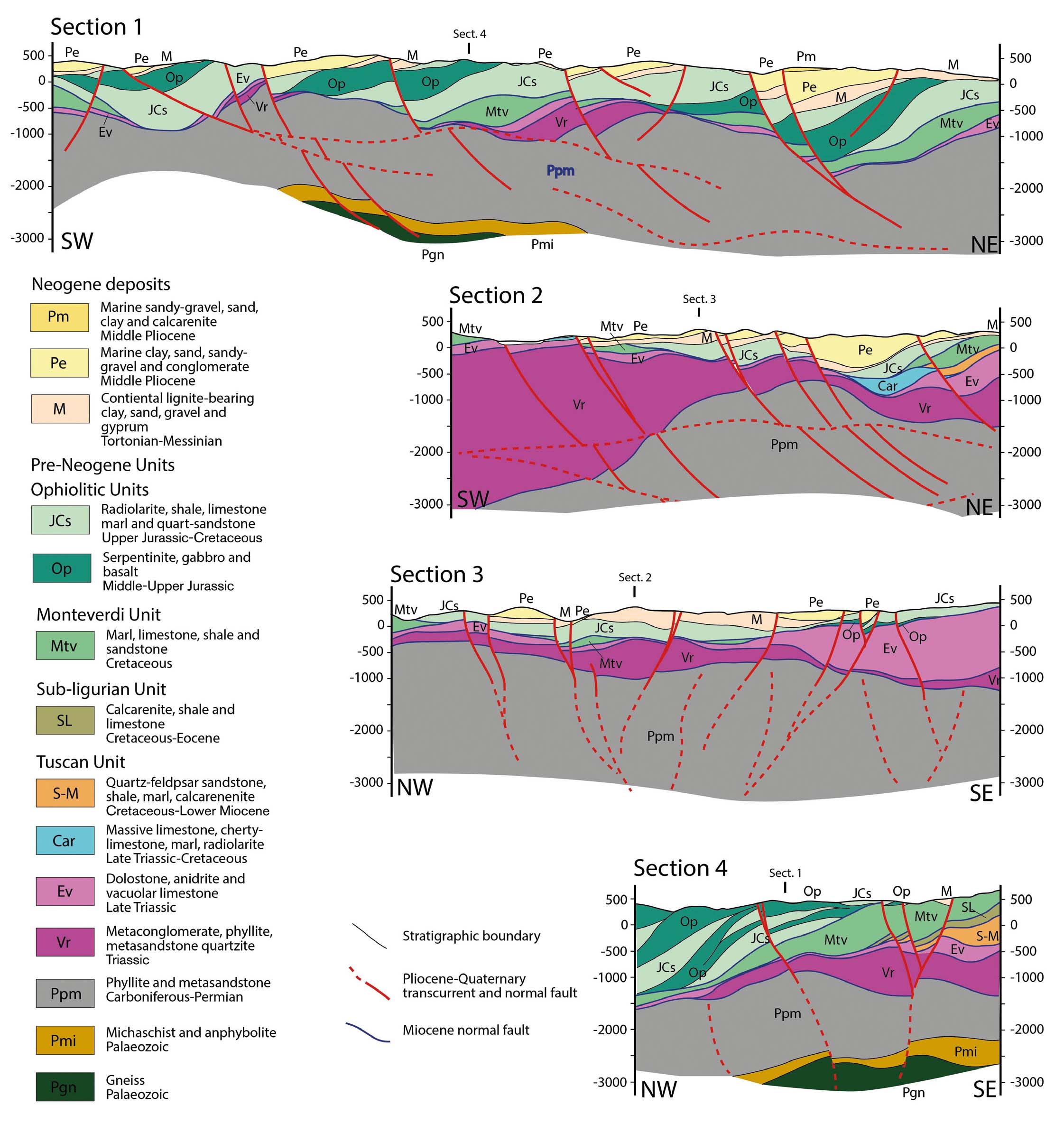

- Geological cross sections through the Larderello and Lago areas. See Figure 2 for their traces (after Liotta & Brogi, 2020, modified).

What is referred to as Geothermal derives from the heat released from Earth interior toward the Earth surface. The total terrestrial natural heat release is estimated in the order of 44.2 x 1012 W per time unit, considering a global mean heat flux of 87 mWm-2 (Pollack et al., 1993).

The crucial point is, therefore, to extract this resource and transport it to the surface. In this process, a vector is necessary and water is the natural medium for its chemical and physical properties. Moreover, water is able to infiltrate the ground and interact with rocks and deep fluids to become a hot and mineralised geothermal fluid, before emerging in natural springs or being tapped by geothermal wells. In this simple conceptual path, the work of the man is to intercept the geothermal fluids reservoir, providing methodologies for exploration and sustainable use of this natural and renewable resource. In this text, we summarise the progress through a historical journey in the Larderello area, that is the birthplace, in 1904, of the use of geothermal fluids to produce electricity.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF GEOTHERMAL USE

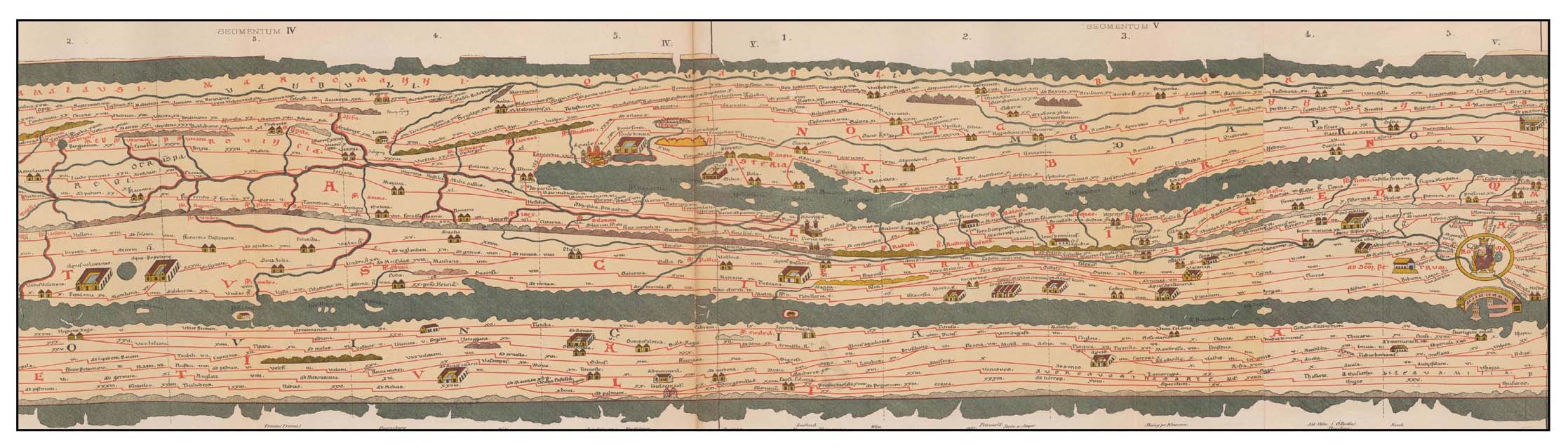

Human beings are known to be attracted by natural hot springs since the Iron Age (XII-IX centuries BC), at least, by building settlements and places of worship near to the thermal areas. During the X century BC, human beings also implemented the use of hydrothermal deposits to produce potters, colorants and mortars (Cataldi, 2005). In Europe, Greeks, Etruscans, and, eventually, Romans introduced the use of thermal baths to promote healthy and social centres since the VIII century BC. This new approach spread throughout the Roman Empire (from Germany to Great Britain, France, Turkey, Hungary and Northern Africa), making the towns with thermal springs attractive and suitable as market centres. For Roman society, thermal localities were so significant to be in road maps, as documented by the Tabula Peutingeriana (Fig. 4), a rolled hand map for the Roman travellers (Levi & Levi, 1967).

- Portion of the Tabula Peutingeriana as it is exposed at the Vienna Hofbibliothek. On the right end (South), Rome; on the left end (North), the geothermal lake that was existing close to the future Larderello village, is reported. The figure displays a portion of the medieval reproduction of the IV century map, showing the main road network of the Roman Empire, from Great Britain to Germany, Africa, Greece and western Asia.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, during the Middle Ages, the use of thermal baths was drastically reduced for political and religious reasons, remaining confined to a few aristocratic families and hosting houses for pilgrims traveling to Rome (Redi, 2005), although between 1300 and 1500, a renewed interest arose for therapeutical uses, after precursor studies to classify the medical properties of each known thermal spring (Zuccolin, 2005).

The first industrial use of geothermal fluids in Italy developed during the beginning of the XIX century, after the preliminary observations carried out by Targioni Tozzetti (1752) and the subsequent chemical analyses by Hoefer (1778) and Mascagni (1779) on the occurrence of Boron in the natural hot springs of the Lagoni, close to the area that we refer to as Larderello (Figs. 1 and 2). Following Burgassi (2005), during the year 1812, a French Society, having François Jacques de Larderel as a partner, activated the industrial production of Boron, obtained after the evaporation of the thermal waters by firewood. However, due to the intense exploitation of the surrounding forest, this procedure became unsustainable after a few years, and the company crashed. François Jacques de Larderel took over the entire corporation and introduced innovative concepts, such as covering the natural emissions with a brick dome construction, thus creating a low-pressure environment which triggered the separation between steam and boron-reach waters. Directly from this construction, steam and boron-rich waters were then separately channelled to the boiler and to the base, respectively, to enhance the precipitation of boric acid, thus enhancing its production and, with it, the Larderel Company’s income.

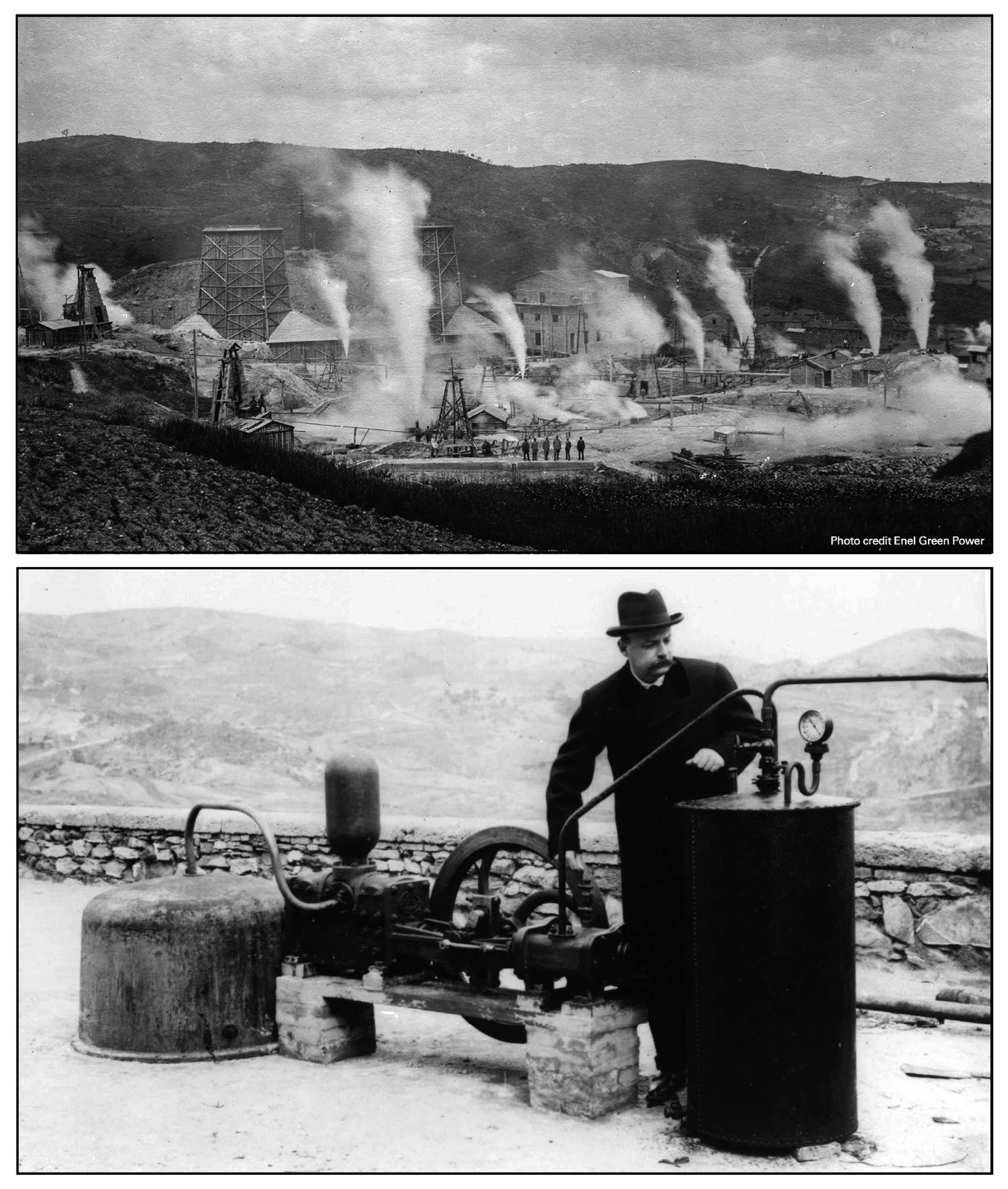

Since the beginning, industrial geothermal activity has been closely connected to Science advancements: an up-to-date chemical laboratory was set up, and several scientists accompanied the exploration and exploitation of fluids, sharing the industrial goals. At the same time, since 1828, several boreholes were drilled close to the natural emissions: a few metres deep, in their initial stages, up to about 200 m depth, in 1856 (Fig. 5). Borehole stimulation, specific drill rods and chisels, and new techniques for casing and cementing were also tested during this period of experimentation. By the end of the XIX century, boreholes reached 300 m depth, and a standard procedure for drilling in geothermal areas was defined (Burgassi, 2005). In this context, specialised workers and scientists, already accustomed to considering the steam a source of energy, were culturally and technically ready to walk in the path of electricity production, overtaking in a few years the technical difficulties of connecting the geothermal fluids to a mechanical engine. In 1904 the first five light bulbs of history were lit by a generator consisting of a dynamo rotating under the pressure of the geothermal steam (Fig. 5). In 1913 the first 250 kW geo-thermo-electric unit operated.

- Historical photos showing (to the top) the construction of the first Larderello power plant (source: https://www.enelgreenpower.com/media/photo/2020/03/larderello/tuscany-history) and (to the bottom) the Prince Ginori Conti, in 1904, next to the first turbine, to produce electric energy from geothermal fluids (source: https://www.unionegeotermica.it/storia-della-geotermia/).

Having now electricity, the production of chemical substances also increased, permitting the production of new boron-derived chemical products. The handling of geothermal steam also improved: since 1910, almost all the industrial laboratories and edifices have been heated by geothermal energy. The electricity production progressively increased, replacing the boron production that declined until being stopped during 1950’s.

Having reached a capacity of 126.8 MWe, in 1943 the power plant was bombed and destroyed during WWII. Only a 23 kWe turbine for didactic purposes survived. The modern Larderello electricity production re-started from here, and the Società Larderello built up geothermal power plants in the Larderello and, since the early ‘60s, in the Mount Amiata regions, maintaining the activity until 1962, when the electricity production was transferred to ENEL (National Electricity Board), which has been ever since managing geothermal exploration, wells drilling and power plants’ construction, operation and maintenance.

UNDERSTANDING THE RESOURCE: FROM THE BEGINNING TO THE END OF THE 1970’S

The first studies on the Larderello geothermal system were devoted to the fluids’ nature and chemical composition. During the 1830-40 time span, a scientific debate on the origin of the geothermal reservoir advanced, although in terms of market competition. Is the geothermal reservoir restricted to the Larderello geothermal spring areas? Or is it broader, deeper, and diffused beyond the Larderello surroundings?

This second view, supported by Gazzeri (1841), implied that even in the areas where no natural manifestations were present, deeper boreholes might be fruitful. Nevertheless, until 1860, the Science input to industry remained static since the production and related income continued to be satisfactory using the already known methods.

Input to renovation occurred in the 1870’s, when new Borax was introduced in the market from California and competition increased. This event led to new investments to implement the already existing Larderello chemical laboratory. In this new frame, several scientists (e.g., Paolo Savi, Leopoldo Pilla, Giovanni Capellini, Bernardino Lotti, Fausto Sestini, Ferdinando Raynaut, Sebastiano De Luca) prepared the floor for the discovery and the study of Argon, Helium, and Radon in the geothermal fluids (Nasini, 1930).

While the analysis of the geochemical fluid characteristics was conducted daily, the issue on the origin and location of geothermal fluids arose at Pisa University: P. Savi and L. Pilla, (both professors of Mineralogy and Geology although in different periods) contrasted to explain the Larderello fumaroles as local expressions, or as similar to what is observed in vicinity of volcanoes, as in the Campania region, respectively (Corsi, 2001). This issue was then suspended by the prematurely Pilla’s passing away, to be renewed years later by G. Capellini (La Spezia, 1833 – Bologna, 1922), who appreciated Pilla’s approach (Corsi, 2001).

As reported by Cataldi & Burgassi (2005), an innovative interpretation was advanced by Stoppani (1875) who proposed the origin of the geothermal fluids as linked to a cooling magma at depth and the tectonic control of the thermal springs, being these aligned following a clear NW-SE direction. Similarly, Lotti (Massa Marittima, 1847 - Roma, 1933) supposed the recent origin (post-Eocene/Miocene) of Tuscan magmas, in contrast with the dominant hypothesis of his period (Marinelli, 1985).

A significant increase in the knowledge of the geological processes governing geothermal resources occurred after WWII and the nationalisation of electricity production. ENEL itself trained and hired throughout the years a valid and qualified staff of researchers who studied several aspects of geothermal topics and power generation, also relying on a vast set of facilities at the Larderello laboratories as well as on drilling rigs and logging tools.

Simultaneously, and often in close collaboration with ENEL and academic personnel, the National Research Council of Italy (CNR) set up a geothermal research unit in Pisa (Tongiorgi, 1973). This unit started its activity in 1963 as Centro Studi Geotermici (Centre for Geothermal Studies) and was consolidated and expanded as a research Institute in 1970, named as: Istituto Internazionale Ricerche Geotermiche – IIRG (International Institute for Geothermal Research). Both the Centre and then the IIRG were promoted by their first Director, the late Prof. Ezio Tongiorgi (Milano 1912 - Pisa 1987), who held the Chair of Nuclear Geology at the Department of Earth Sciences of Pisa University. Throughout the years, the activity of IIRG, which in 2002 merged with another CNR Institute (IGGI – Institute of Geochronology and Isotope Geochemistry) to become a larger Institute (IGG, Institute of Geosciences and Earth Resources), embraced various aspects of geothermal exploration, including geochemistry, geology, geophysics, petrography, reservoir engineering, and hydrogeology.

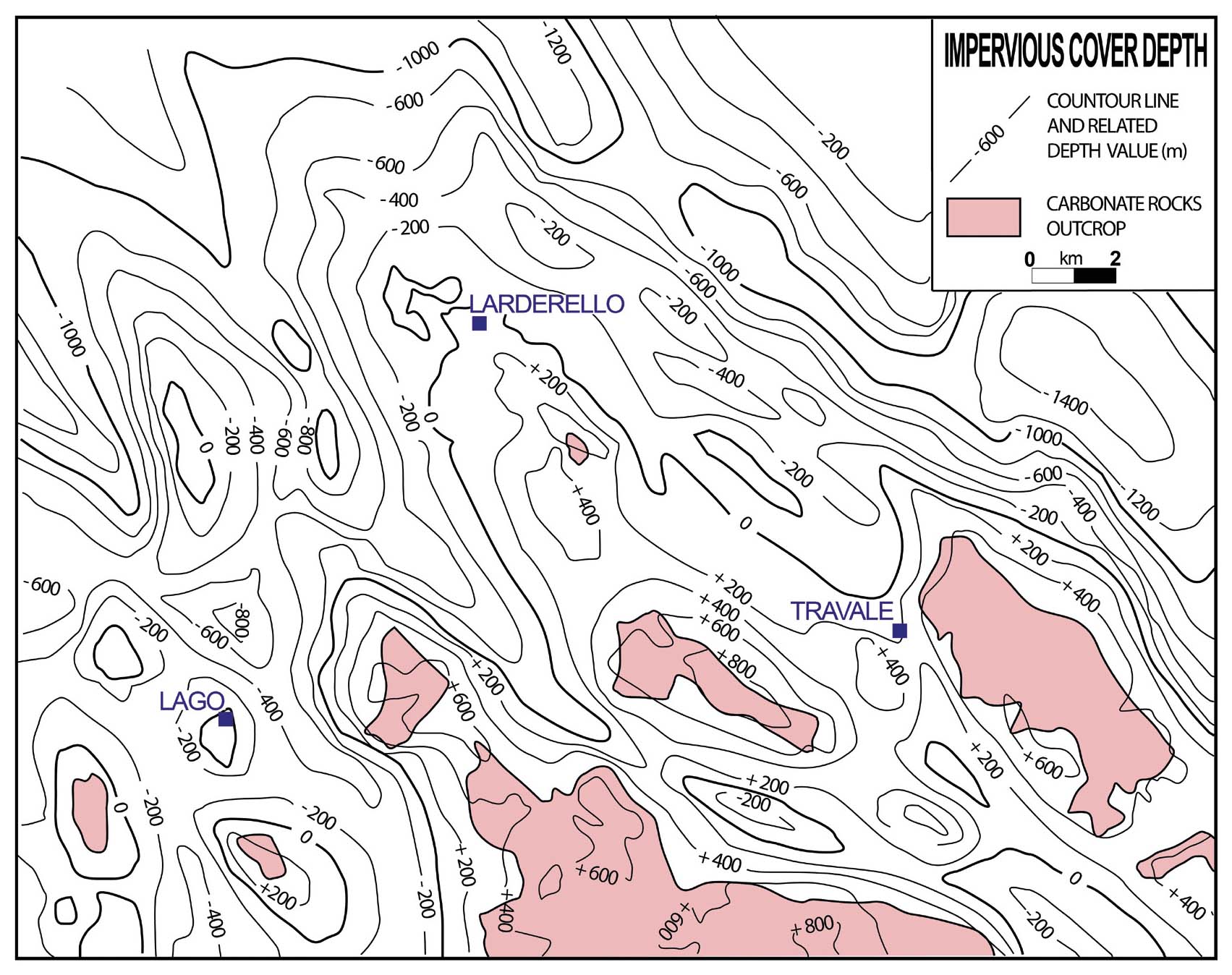

By CNR’s impulse, a new geological survey of the geothermal area was carried out, resulting in the pivotal papers and geological maps provided by Mazzanti (1966), Lazzarotto (1967), Lazzarotto & Mazzanti (1978), where the first integration between borehole and fieldwork data was enhanced. By these studies, the tectonic pile and sedimentary succession of the area were clearly defined, in terms of geometry and palaeontological datings, thus better characterising the composition and geological evolution of the impervious cover and reservoir, which, at that time, was only known in the Calcare Cavernoso, a tectonic breccia deriving from the deformation of the Upper Triassic evaporite and in the overlying Jurassic carbonate rocks, located at the base of the sedimentary cover (Fig. 6). A synthesis of the reservoir geometry was given by Gianelli et al. (1978) and Minissale (1991), by mapping the base of the impervious cover, mainly corresponding to the roof of the Calcare Cavernoso (Fig. 7), and ranging in depth between 200 m and 800 m b.g.l. A similar approach was proposed for the Monte Amiata Geothermal area, where Calamai et al. (1970) provided new maps concerning the geothermal gradient distribution, geology and hydrogeology of the area.

- The rock succession in the Larderello area: left: stratigraphic column (after Lazzarotto, 1967), illustrating the succession of the Ligurian, Sub-Ligurian and Tuscan units: from the bottom: a - quartzite and phyllite belonging to the Verrucano Group, Auctt. (Triassic); b - Calcare Cavernoso, made up of a tectonic breccia deriving from dolostone and anhydrite (Upper Triassic) and corresponding to the so-called “first reservoir”; c - Jurassic carbonate sequence; d - Cretaceous-Oligocene marl; e - upper Oligocene-Lower Miocene sandstone; f - calcarenite, shale and limestone (Cretaceous-Oligocene); g - marl, limestone and shale (Cretaceous); h - serpentine, gabbro, basalt and radiolarite, Jurassic; i - shale, limestone, marl, sandstone (Cretaceous). Right: schematic column representing the structural relation among the geological bodies in the Larderello area (after Bellani et al., 2004, modified)

- Depth of the impervious cover in the Larderello area and surroundings (after Minissale, 1991, redrawn).

Simultaneously, studies on the fluid properties continued, better defining the characteristics of the hydrothermal fluid hosted in the reservoir, as derived by the interaction with the Triassic anhydrite level (D’Amore & Squarci, 1979). These studies evidenced that the reservoir fluid is a super-heated dry steam, of about 150-250 °C and pressure up to 20 bar, as later indicated by Minissale (1991) and Romagnoli et al. (2010). The fluid contains a small percentage of ammonia and boric acid (D’Amore et al., 1977). The content of Tritium (Celati et al., 1973; D’Amore et al., 1983) further suggested that the contribution of meteoric water (Panichi et al., 1974) is through a long circuit (Calore et al., 1982).

UNTIL TODAY

During the last years of 1970’s, the geothermal production showed a decline. This evidence, together with the oil crisis of those years, gave a new impulse to the exploration of new areas (e.g., Travale area, to the SE of Larderello) and deeper reservoirs. The latter were finally reached in the fractured crystalline basement in both the Larderello and the Amiata areas (Fig.1). The Larderello deep reservoir is characterised by super-heated dry steam with a pressure up to 70 bar and temperature of 300–350 °C (Barelli et al., 1995; Romagnoli et al., 2010). Apart from differences deriving by local conditions (Scandiffio et al., 1995; Gherardi et al., 2005), the deep fluids show similarities, even through the geological time (Magro et al., 2003), to the ones already known in the shallow reservoir (Bertini et al., 2006, with references), now referred to as the first reservoir.

Almost in the same period, condensed and cooled geothermal fluids started to be re-injected in the marginal parts of the geothermal area, from where the meteoric water was already supposed to inflow into the geothermal system. Re-injection was aimed at recovering the heat from the rocks, which was still present after the extensive exploitation of the natural geothermal fluids hosted in the Calcare Cavernoso reservoir (Cappetti et al., 1995). The success of this procedure encouraged its implementation, resulting in a key factor for maintaining the pressure constant in the geothermal system, up to the Present time. As a result of re-injection, enlargement of the drilled area and deep reservoir contribution, fluid production increased in the Larderello field to reach about 3700 t/h (Arias et al., 2010; Barelli et al., 2010; Romagnoli et al., 2010).

Deep boreholes, down to about 5 km, displayed the nature of the basement rocks, affected by HT-metamorphism, of increasing metamorphic degree to depth, suggesting a progressive approach to a cooling magmatic body (Castellucci et al., 1983; Puxeddu et al., 1984; Cavarretta & Puxeddu 1990; Elter & Pandeli, 1990; Bertini et al., 1991; Pandeli et al., 1994; Musumeci et al., 2002; Boyce et al., 2003), located at depths not yet reached by boreholes (Gianelli et al., 1997a, and references therein).

This is consistent with the low-gravity anomaly in the area, suggesting a partially molten crust at mid-crustal levels (Gianelli et al., 1997a), that is matching with the results of inversion of teleseismic earthquake analyses (Foley et al., 1992; Batini et al., 1995), modelling (Rochira et al., 2018), the thickness of the crust and lithosphere, estimated in about 22 and 40 km, respectively (Calcagnile and Panza, 1981; Locardi & Nicolich, 1992; Di Stefano et al., 2011) and heat flux (Fig. 8), up to 1000 mWm-2 (Mongelli et al., 1998; Della Vedova et al., 2001).

- Heat flow distribution (contour lines in mWm-2, after Bellani & Gherardi, 2013) in the Lago and Larderello areas. The base map is described in Fig. 2.

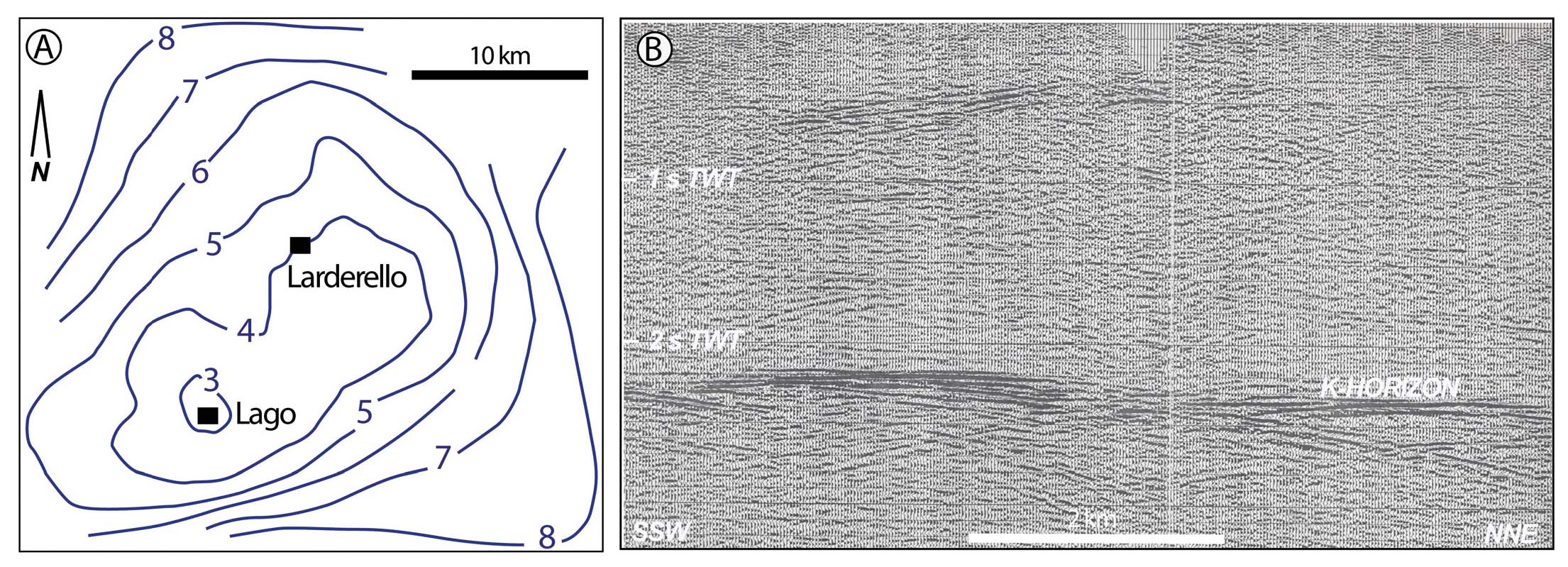

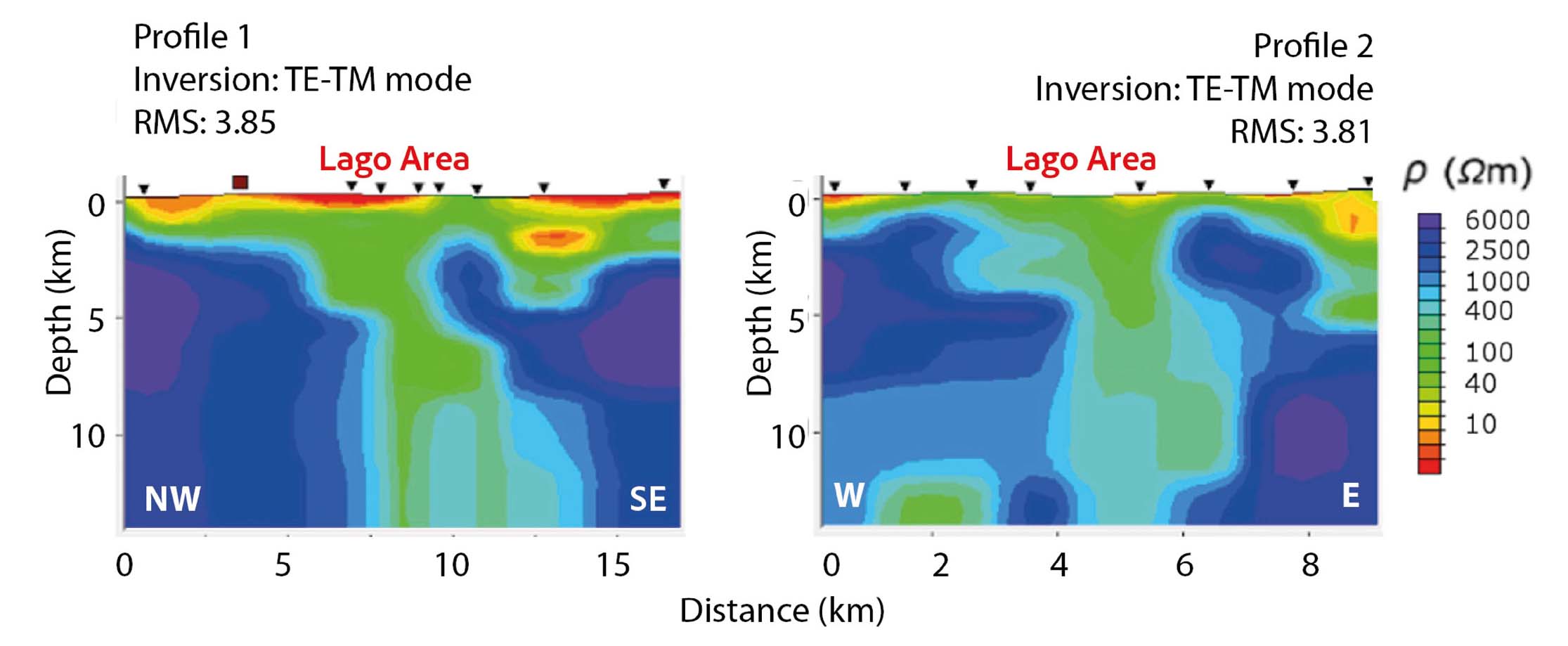

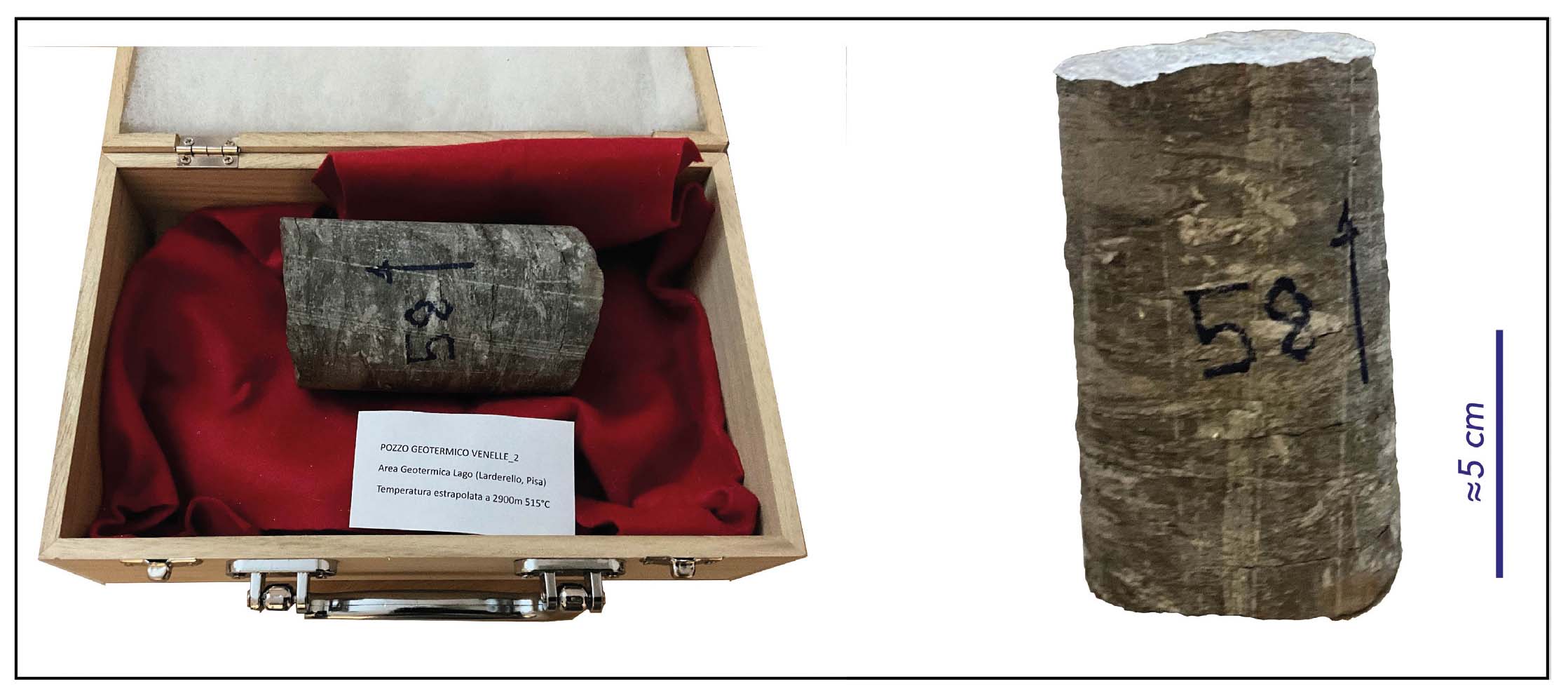

Exploration and exploitation of the basement resources is, however, a long process, which brought to acquire reflection seismic lines. The first reflection seismic line (LAR 1), was acquired in the early 1970s, in the surroundings of Larderello village, and already displayed a mid-crustal bright reflector, affecting the basement rocks. This reflector, named K-horizon (Batini et al., 1978), was later imaged in the following acquisitions, ranging in depth between 3 and 7 km (Fig. 9), thus resulting as a possible target of exploration and argument of scientific debate. This implements the concept of a relatively shallow (about 6-8 km depth; Foley et al., 1992; Batini et al., 1995) magmatic source in the Lago area. A similar conclusion was then reached by magneto-telluric (MT) studies (Fig. 10) that highlighted a low resistivity channel particularly matching with the Lago area (De Angelis et al., 1998; Manzella, 2004; Rizzo et al., 2022), where the heat flux is significantly high (Fig. 8). All these convergent data constituted the background of the DESCRAMBLE project (https://www.descramble-h2020.eu) that brought to drill in the superhot system, where temperature likely exceeds 500 °C at about 3 km depth (Fig. 11), to find the possibility to have supercritical geothermal resources (Bertani et al., 2018).

- Left: K-horizon depth, as estimated after Cameli et al. (1998); right: example of the bright mid-crustal reflector (unmigrated seismic section), named as K-horizon, delimiting at the top the typical seismic facies with lozenge shape reflectors (after Cameli et al., 1993, modified).

- 2D MT profiles in the Lago basin area, showing low resistivity values (green colors) down to the depth of over 10 km in the Lago area (after Rizzo et al., 2022, modified). The traces of the MT profiles are displayed in Fig. 2.

- Micaschist sampled in the deep borehole Venelle (Lago area) at depth of 2900 m b.g.l., and estimated temperature of 515 °C. It was donated by ENEL Green Power Ldt. to the Department of Earth Sciences of Pisa University, November 29, 2023.

THE GEOTHERMAL SYSTEM

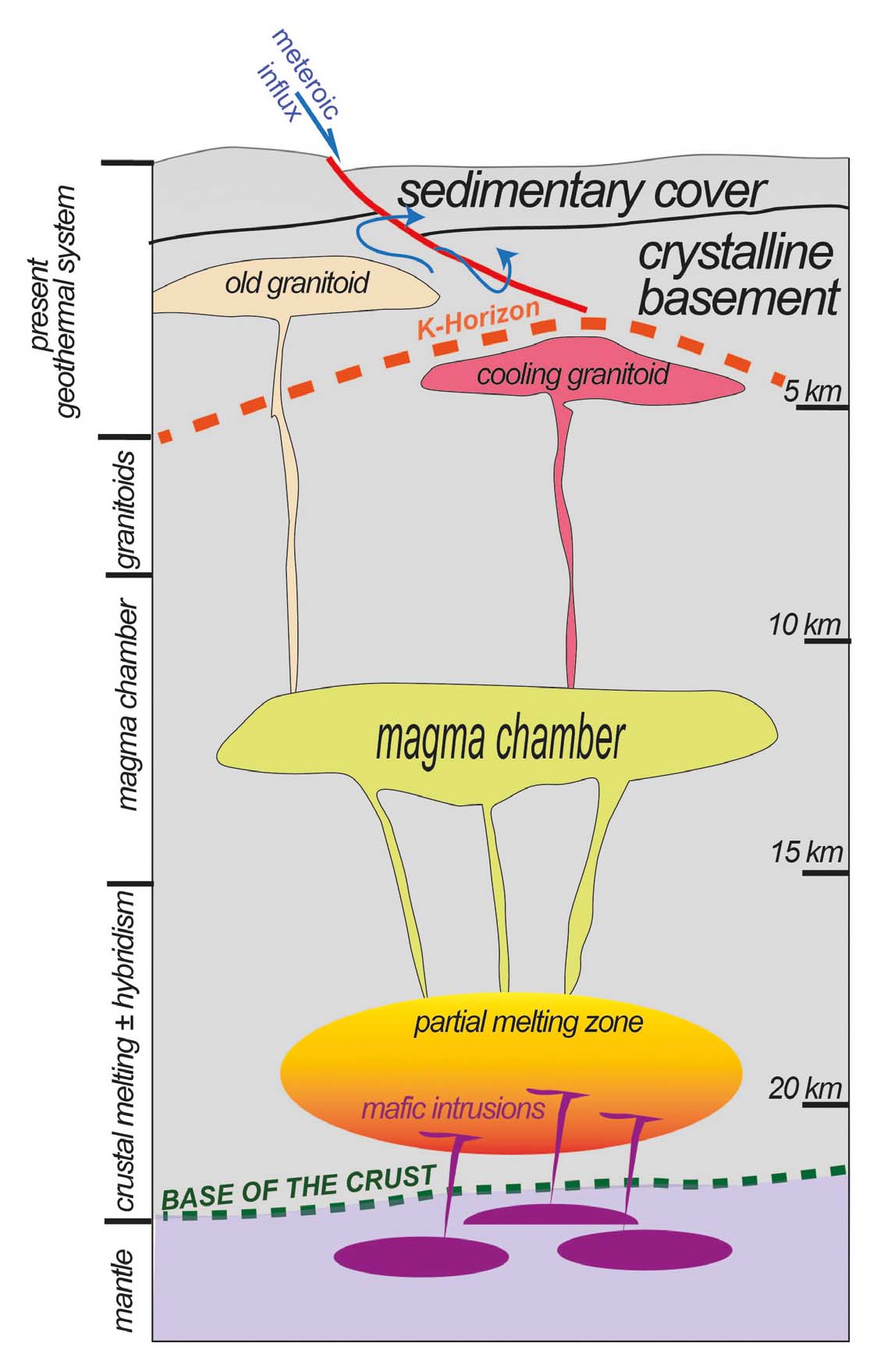

Together with these progresses, the study of the geological evolution of the Larderello geothermal system has been developing, focusing on the three main issues of such a system, i.e., the heat source, fluids and structures. Regarding the nature of the heat source, i.e. the cooling magma, the main documentation derives from the study of the analogue, now cropping out, Tuscan granites and from the boreholes which encountered magmatic bodies at depth (depth range 3–5 km), in the geothermal area (Del Moro et al., 1982; Villa et al., 1987; Villa & Puxeddu, 1994; Villa et al., 1997; Gianelli et al., 1997a; Carella et al., 2000; Gianelli & Laurenzi, 2001; Villa et al., 2001; Gianelli & Ruggieri, 2002; Laurenzi, 2003; Villa et al., 2006). By this double approach, Dini et al. (2005) recognised multiple injections of mainly acidic peralluminous magmatism affecting the present geothermal area, since the Pliocene. Furthermore, they inferred distinct crustal sources at different depths, from which the magma partitioning favoured the long-lived activity of the geothermal system, up to Present time (Fig. 12).

- Conceptual sketch on the origin and magma transfer through the crust of the Larderello geothermal area (after Dini et al. 2022, modified)

In the frame of the geothermal evolution, fluid inclusions were pivotal to reconstruct the past fluid flow condition (i.e. before the present-day steam-dominated state) and the hydrological evolution of the system (Belkin et al., 1985; Valori et al., 1992; Petrucci et al., 1993; Cathelineau et al., 1994; Gianelli et al., 1997b; Ruggieri & Gianelli, 1999; Ruggieri et al., 1999; Ruggieri & Gianelli, 2001; Boyce et al., 2003; Dallai et al., 2005; Boiron et al., 2007). The results of fluid inclusion analyses in calcite veins from relatively shallow depth samples (<1.2 km) drilled within the sedimentary cover close to the contact of the shallow reservoir show range of salinity from 1.7 to 22.2 wt.% NaCl eq., homogenisation temperatures from 224 to 296 °C and the occurrence of boiling process (Gianelli et al., 1997b). These fluid inclusions likely record the past features of the upper part of the shallow reservoir, characterised by boiling and the contemporaneous circulation and mixing of meteoric waters and saline fluids possibly derived from evaporite layers of the Mesozoic carbonates or Neogene and mobilised during geothermal activity.

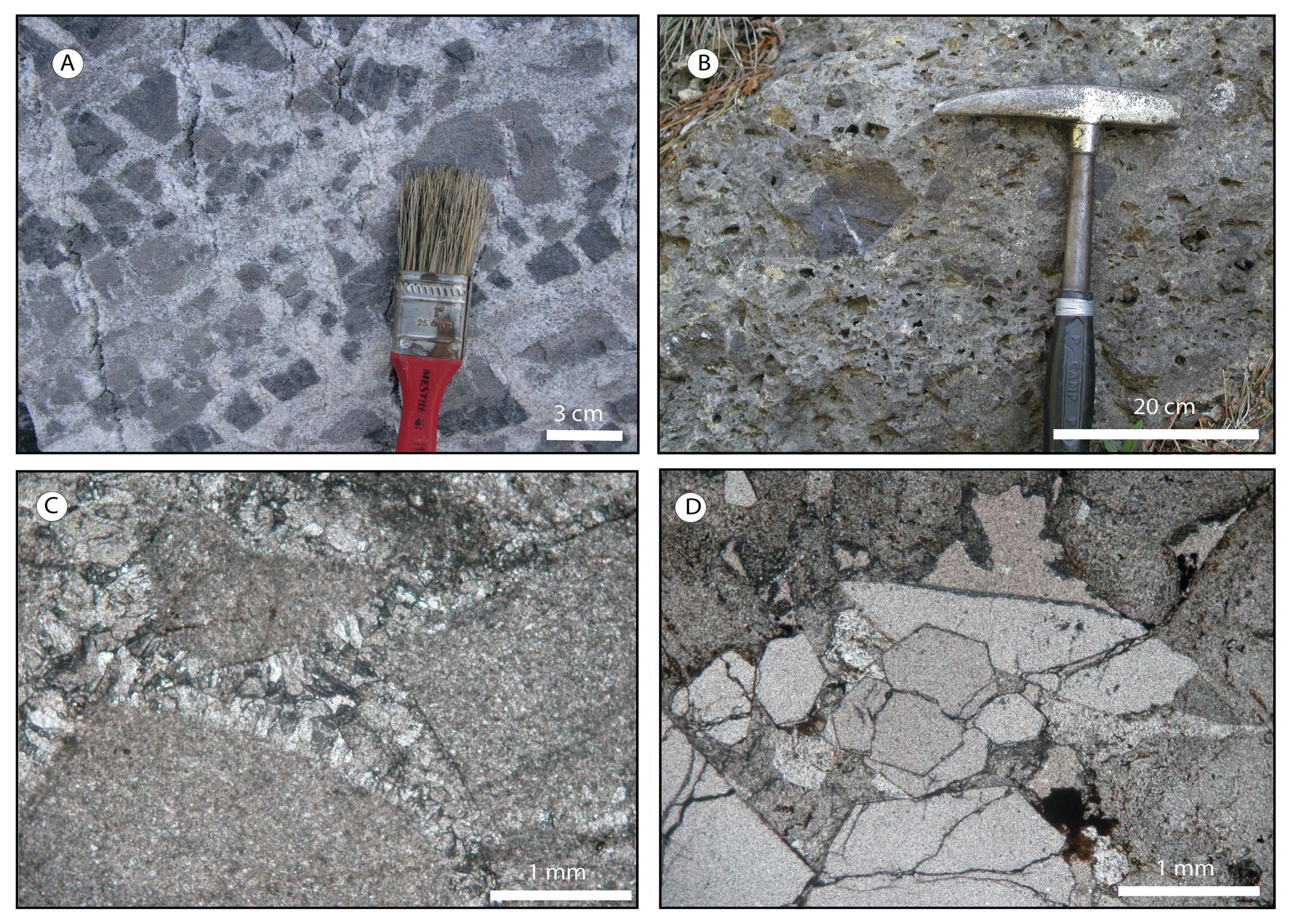

Circulation into the upper reservoir is influenced by the cataclastic texture of the Upper Triassic anhydrite hosting rock, since it played the role of a main detachment level during the collisional and subsequent extensional stage of inner Northern Apennines, thus resulting in a regional tectonic breccia constituted by dolostone elements embedded in a calcium-sulphate matrix (Fig. 13). Moreover, fluid inclusions from a hydraulic breccia indicated that the upflow of hot pressurised fluid at relatively shallow depth triggered brecciation and contributed to the permeability of the reservoir (Ruggieri & Gianelli, 1999).

- Outcrop and thin section photos of the cataclasite developed within the Upper Triassic evaporite level. A - Clasts of dolostone embedded in gypsum, derived from hydration of anhydrite; B - when gypsum is dissolved, a breccia composed of dolostone clasts within a calcareous matrix and cement is displayed; C - thin section showing the cataclasite with carbonate clasts and calcite cement; D - hydrothermal quartz substituting the cement (after Liotta et al., 2010, modified).

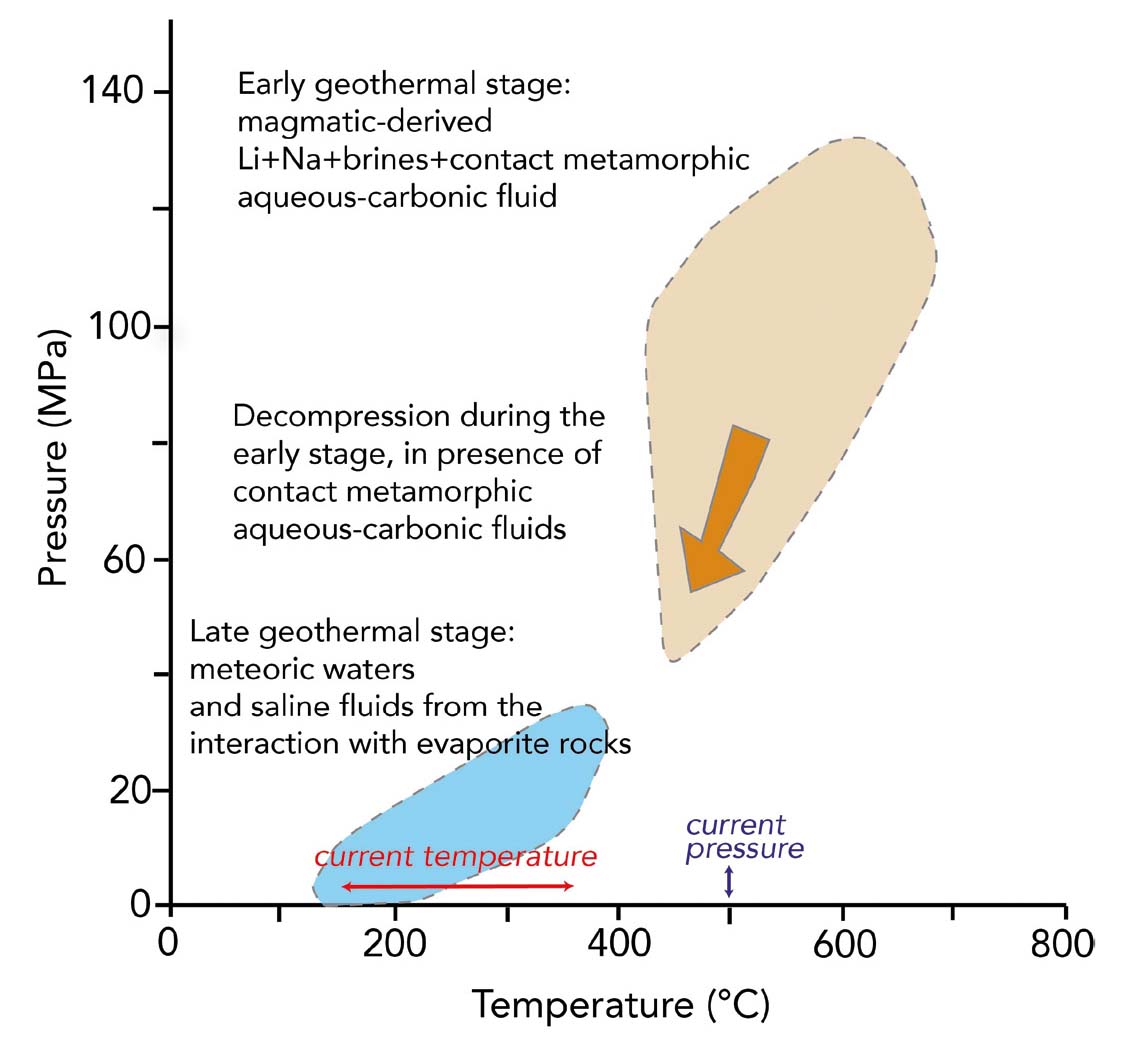

At deeper structural levels (>2.5 km), fluid inclusions from borehole samples of granitoids and contact-metamorphic mineral assemblages record two stages of geothermal circulation. The early stage, documented by several generations of fluid inclusions, was characterised by the nearly concomitant circulation and interaction of Li-Na-bearing brines of magmatic origin and aqueous-carbonic fluids, resulting from the heating of Paleozoic rocks during the HT-metamorphic event (Valori et al., 1992; Cathelineau et al., 1994; Ruggieri & Gianelli, 2001; Boiron at al., 2007). This process developed at temperatures of 420–690 °C, initially under lithostatic pressures of approximately 90–130 MPa, and subsequently at sub-lithostatic pressure, as recorded by aqueous-carbonic fluid inclusions (Fig. 14). These early fluid inclusions were interpreted to be trapped within a palaeo K-horizon, and now occur above the present K-horizon because of rock uplift and/or cooling of the system (Boiron et al., 2007).

- P-T diagram illustrating the evolution of the geothermal fluids in the Larderello area (after Gianelli & Ruggieri, 2002, modified).

The second stage of geothermal circulation at deep level developed when the system decompressed at hydrostatic values and the temperature decreased below 400 °C (Fig. 14). Fluid inclusions of this stage record circulation of fluids with variable salinities and are interpreted as meteoric-derived fluids. These changed composition, salinity and temperature during their fluid path by processes of water–rock interaction (particularly with the evaporite), fluid boiling, mixing and cooling processes (Valori et al., 1992; Gianelli et al., 1997b; Ruggieri & Gianelli, 1999; Ruggieri et al. 1999; Boyce et al. 2003). Finally, the geothermal system evolved toward the present-day conditions, characterised by vapor-static pressure and temperature of about 150–350 °C (Fig. 14).

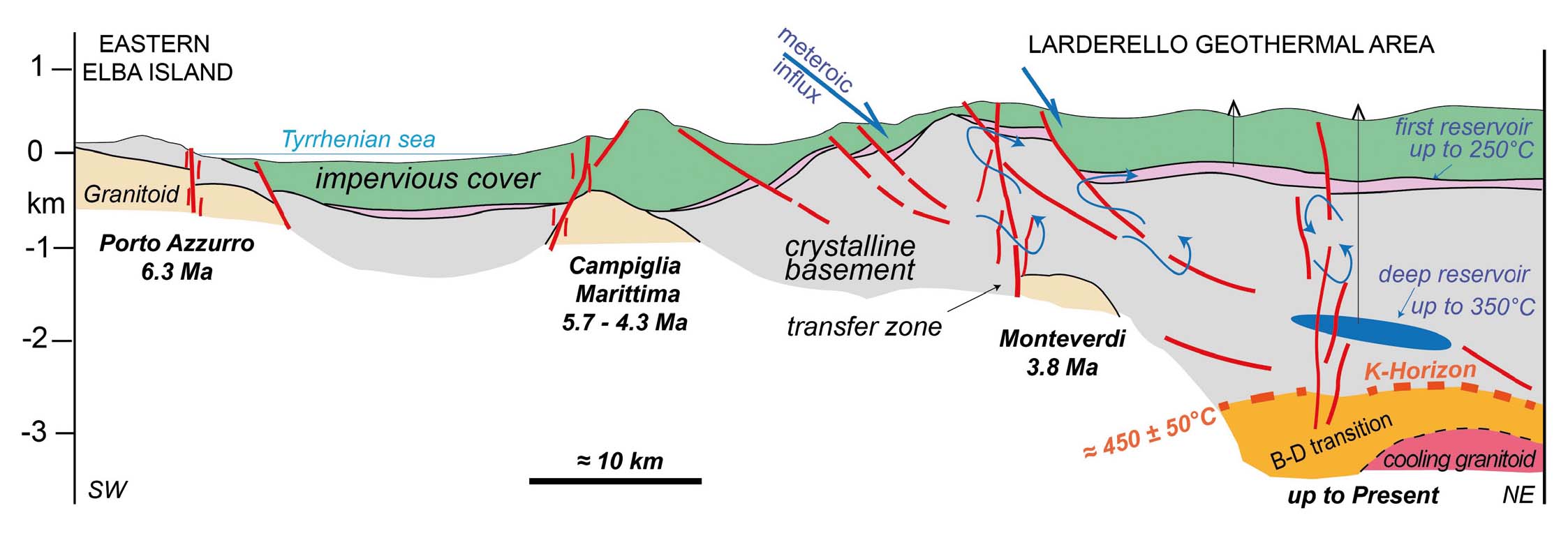

In the frame of the eastward migration of magmatism and extension, the contribution of a deep hydrothermal fluid (Celati et al., 1991) of supposed magmatic origin (D’Amore & Bolognesi, 1994) is strictly connected to brittle deformation (Fig. 15), the latter ensuring permeability and hydraulic conductivity, that is mostly determined by NNE trending sub-vertical fractures (Batini et al., 2002), associated with regional scale fault systems, i.e. transfer zones (Liotta & Brogi, 2020). A similar framework is also offered by studying the geothermal evolution of Eastern Elba Island, believed to be an analogue, i.e. fossil geothermal system, of the Larderello area, since it developed during the Messinian in the same geodynamic context (Dini et al., 2008; Liotta et al., 2015; Zucchi et al., 2017; Spiess et al., 2021; Liotta et al., 2021; Spiess et al., 2022; Zucchi et al., 2022; Zucchi et al., 2024).

- Structural sketch on the present setting of the Larderello geothermal system in the frame of the eastward migration of magmatism, exhumation, uplift and extensional tectonics, this latter represented by normal and transfer faults favoring circulation of fluids (after Dini et al., 2022, modified). Cooling ages, from: Spiess et al. (2021), Borsi et al. (1967) and Villa et al. (1987).

Based on thermal and structural data, Bellani et al. (2004), showed that the main NW-trending extensional shear zones are also permeable sectors, favourable for the down-flow and up-flow of meteoric and hydrothermal fluids, respectively (Taussi et al., 2022; Granieri et al., 2023; Taussi et al., 2023).

The occurrence of SW-NE trending faults in the Larderello area, was already defined by the precursor work of Lazzarotto (1967) who recognised this fault system associated to the regional NW-SE trending faults, both representing the dominant structural features of the Larderello area (Fig. 1), as later documented by new borehole, fieldwork and geophysical data (Batini et al., 1978; Bartolini et al., 1982; Batini et al., 1983; Bertini et al., 1991; Cameli et al., 1993; Baldi et al., 1994; Bertini et al., 2006).

Kinematics of the NE- and NW-trending structures was recently investigated by Liotta & Brogi (2020) who explained the NE-structures as strike to oblique-slip faults, associated with the regional transfer zone of which the NW-trending normal faults can be part, contributing to determine the Pliocene Lago Basin. NE-structures also played the role of normal faults, when re-activated.

Given the dominant kinematics characterising transfer faults, these can result as the most favourable sector to promote fluid circulation (Corti et al., 2005; Dini et al., 2008), being able to create vertical permeability (Faulkner & Armitage, 2013, with references therein). A further feature favouring vertical permeability and its maintenance through time, is the intersection with other active structures (Curewitz & Karson, 1997), i.e. the associated normal faults, in the Larderello case.

The coexistence of strike- to oblique-slip and normal movements is also supported by the analysis of the present seismicity (Batini et al., 1985; Montone et al., 1999; Montone et al., 2004; Albarello et al., 2005) to which no-double couple microearthquakes are associated, thus envisaging a fluid pressure contribution in the local seismicity (Console & Rosini, 1998; Kravanja et al., 2000), in the frame of the local stress field defined by a NE-oriented Shmin (Mariucci et al., 1999).

Analyses of palaeo-stress by inversion of kinematic data from fault surfaces indicate that the present stress field can be considered active at least since the Zanclean (Liotta & Brogi, 2020). Furthermore, the interplay between uplift, induced by the heat flux, and extensional tectonics, can also explain the reactivation of the NE-trending faults as normal faults, when uplift is dominant, thus describing the double couple extensional focal mechanisms with NE-trending nodal plane (Console & Rosini, 1998), although parallel to the transfer fault system (Liotta & Brogi, 2020).

DISCUSSION

The close cooperation between industry and research centres brought to a better understanding of the Larderello crustal deep structure and its tectonic evolution. In this view, it is worth underlining the numerous spin-off of scientific collaboration: (i) the creation of the renowned international scientific journal Geothermics that started its activity in 1970, and was a format property of CNR-IIRG until 2008 (the Journal is still currently published under the property of Elsevier); (ii) the training activity, held in Pisa and organised by CNR-IIRG under UNESCO auspices as the: “International Post-graduate course in Geothermics” from 1970 to 1984, with the aim to prepare professionals from developing countries and coordinators of future geothermal projects. It became the “International School of Geothermics” and ran for 9-months with yearly courses (Dickson & Fanelli, 1990). A precursor of this teaching activity was the first course on geothermal issues held by G. Marinelli in cooperation with CNR researchers and ENEL specialists, during 1970. Between 1970 and 1992, approximately 300 geothermal students from about 70 countries were trained, and lessons in Pisa were given by the best available geothermal experts worldwide. From 1992 to 2002, the activity of the School continued with short courses on specific topics held in various countries; (iii) the Inventory of National Geothermal Resources (1994), where all the available data from thousands of wells (hydrocarbon, geothermal, water) and thermal springs where gathered and classified, resulting in the Banca Nazionale Dati Geotermici – BNDG (National Geothermal Database, Barbier et al., 2000), a computer database with a complete dataset from more than 2700 wells and 500 thermal springs. The database has since been updated both in terms of content and management tools becoming the “Geothopica” information platform (https://geothopica.igg.cnr.it/index.php/it/), with webGIS tool to access and visualise multiple types of datasets, and a series of documents of reference for the geothermal sector (Trumpy & Manzella, 2017).

Regarding the deep structure of the Larderello area, many studies were carried out to investigate the nature of the K-horizon. Batini et al. (1978) discussed different hypotheses but, due to the reflections below the K-horizon, doubted that it could be the top of a granite related to the geothermal anomaly. Puxeddu (1984) suggested that the K-horizon could correspond to the top of the Hercynian basement, consisting of metamorphic rocks and granites similar to those outcropping in Sardinia. Batini et al. (1983) and Batini et al. (1985) proposed that the K-horizon was corresponding to a level of fractured rocks, saturated with hydrothermal fluids and minerals. Such a condition could cause a strong contrast in acoustic impedance which may explain its high amplitude. Similarly, Gianelli et al. (1988) suggested that the K-horizon in the Monte Amiata geothermal field could be related to a level characterised by hydrothermal, thermo-metamorphic minerals and fluids, located in the fractured zone just above the top of an igneous body.

Considering the supposed temperature at the K-horizon depth of about 450±50 °C and the distribution of the local earthquakes, Cameli et al. (1993; 1998) and Liotta & Ranalli (1999), explained this reflector as the top level of the rheological brittle-ductile boundary, activated as a shear zone with trapped fluids (Cameli et al., 1993; Liotta & Ranalli, 1999; Vanorio et al., 2004), in the frame of the extensional tectonics affecting the area (Bellani et al., 2004) or as the consequence of α–β transition of quartz (Marini & Manzella, 2005). K-horizon was therefore interpreted as a possible, future, geothermal target since its discovery and where fluids in supercritical conditions might be hosted (Bertani et al., 2018) or a favourable site for “hot dry rock” projects to produce fluids at supercritical conditions (Boiron et al., 2007).

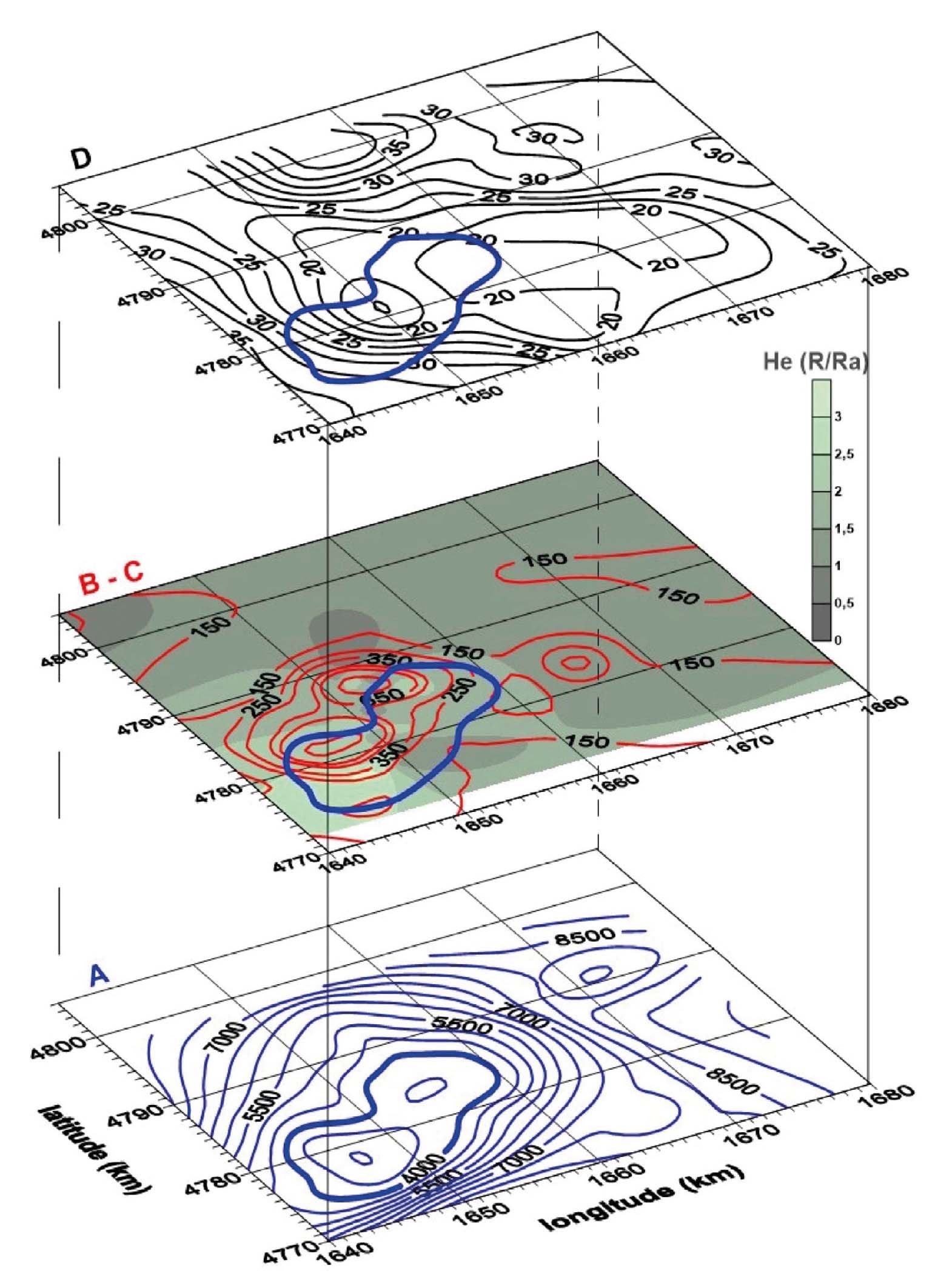

Moreover, the depth of the K-horizon shows a clear relation with the geochemical (distribution of the He isotopes expressed as R/Ra) and geophysical (surface heat-flow and Bouguer gravity anomaly) parameters (Fig. 16), thus underlining the necessity to explain these convergent data in the same context and the validity of considering the K-horizon as a peculiar target (Magro et al., 2003; Bellani et al., 2005).

- Regional comparison among: A - K-Horizon seismic reflector isobaths in m, b.g.l.; B - He isotopic Ratio R/Ra; C - surface heat flow in mWm-2, red contour lines; D - Bouguer gravity anomaly in mGal, for Larderello and neighbouring areas (after Bellani et al., 2005).

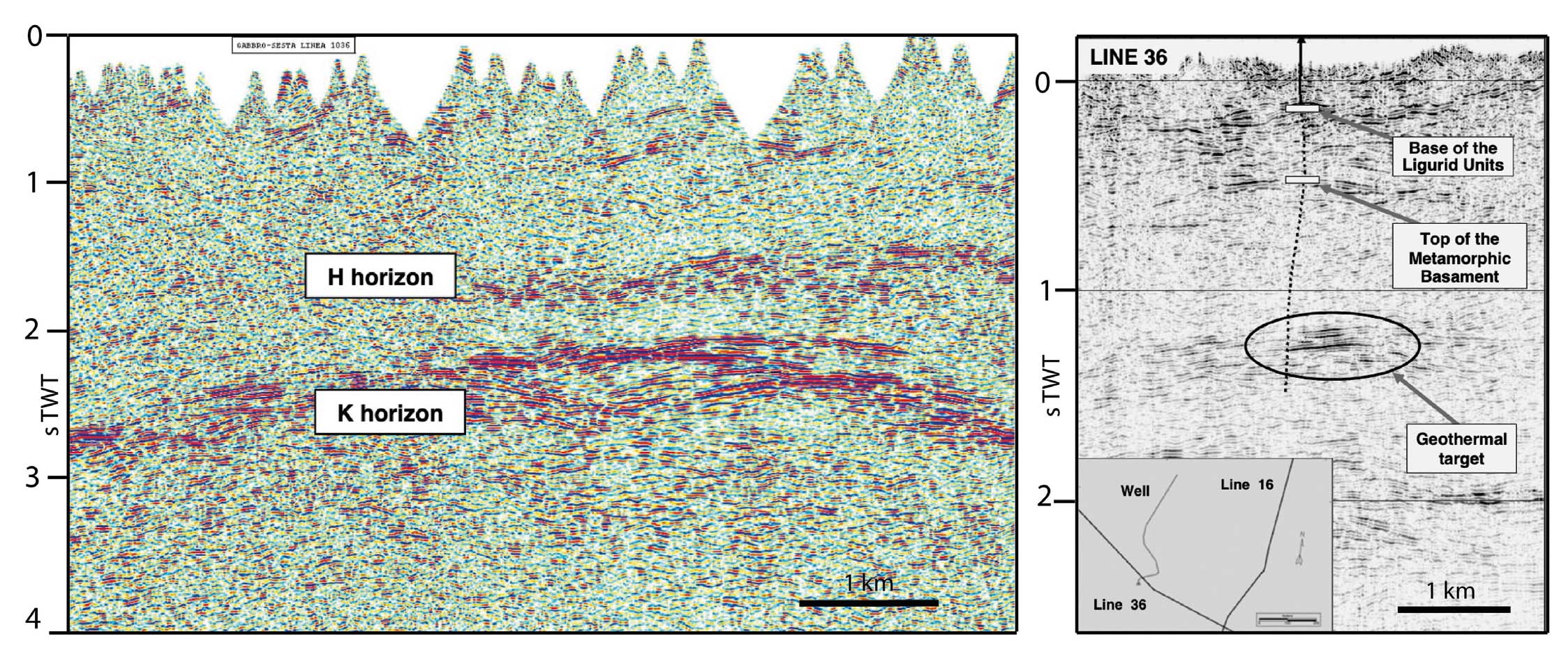

However, current exploitation is addressed to a minor reflector, referred to as H-horizon (Bertani et al., 2005), still affecting the basement rocks above the K-horizon (Fig. 17), and mostly imaged in about NNW-SSE oriented reflection seismic lines. The H-horizon, when reached by boreholes, mainly resulted productive with fluids of meteoric origin (Bertini et al., 2006; Casini et al., 2010). Brogi et al. (2003) interpreted the H-horizon as imaged by the intersection between the plane of the seismic section and the NE-dipping extensional brittle shear-zones, these latter flattening at the brittle ductile transition.

- Examples of the H-horizon (geothermal target) and its depth relation with the K-horizon, as imaged by reflection seismic lines (after Cappetti et al., 2005, modified).

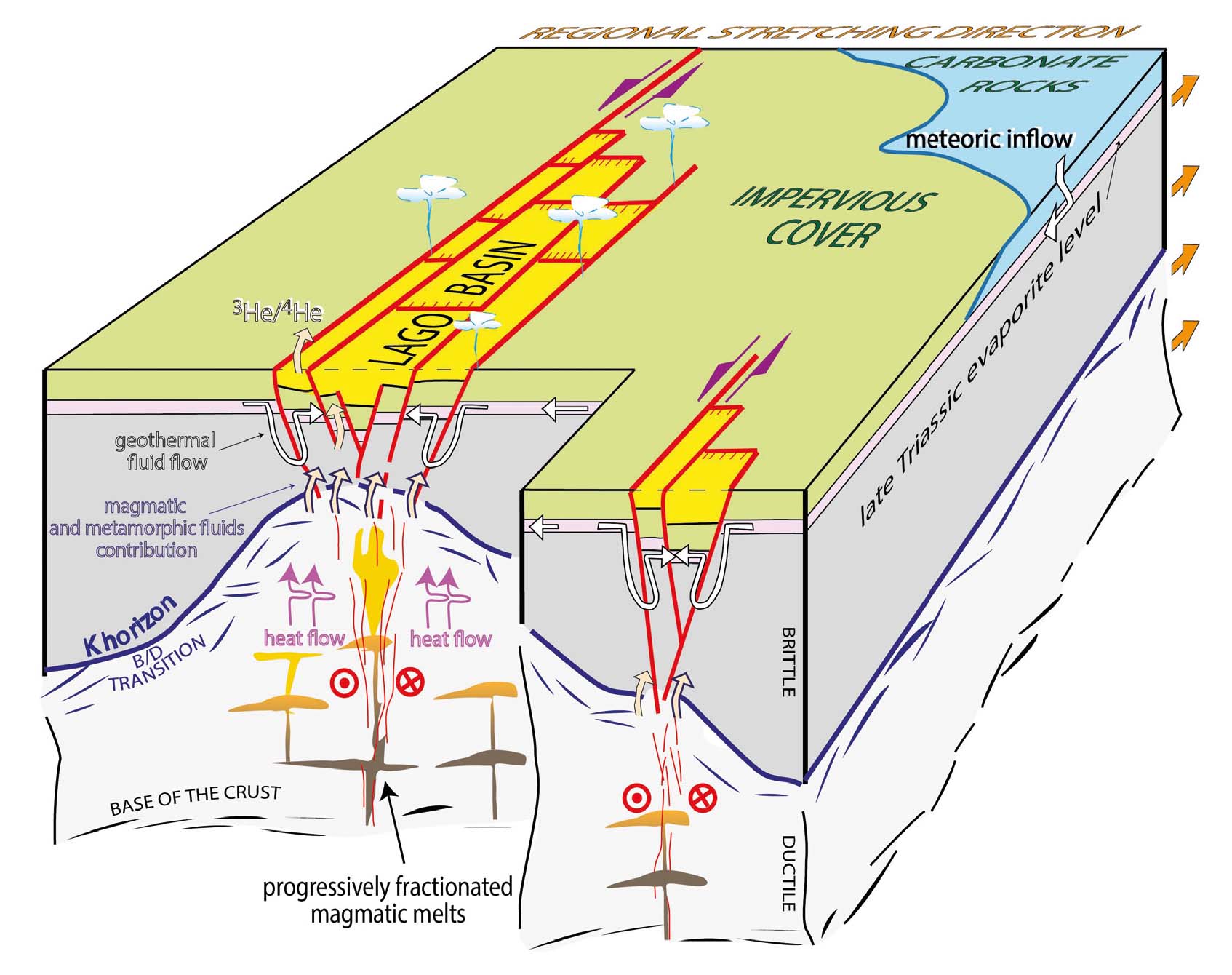

The interplay among HT-metamorphism, the role of transfer and normal faults and circulation of meteoric waters as the main source for the hydrothermal resources, brought to describe a conceptual model (Fig. 18) where the fluid flow is driven by regional shear zones, to which the Calcare Cavernoso is hydraulically connected (Liotta et al., 2010; Liotta & Brogi, 2020). This view implies a crustal relevance of the transfer zone, that is however suggested by the crustal reflection seismic line named CROP 18 (Brogi et al., 2005; Della Vedova et al., 2008), passing through the Lago area (Figs. 1 and 2). Here, from mid crustal level to depth, reflectors are concave-shaped, thus indicating an evident decrease of the seismic velocity (Doll et al., 1996; Stern & McBride, 1998), as it occurs when the seismic waves travel across a cooling magma (Della Vedova et al., 2008; Liotta & Brogi, 2020). Hence, it implies that the shear zone offered the best permeability conditions for emplacement of magmas, currently cooling (Dini et al., 2008; Gola et al., 2017).

- Geological sketch (not to scale) illustrating the tectonic context in which the Lago Basin is located. This is interpreted as a pull-apart basin developed within the transfer zone affecting the geothermal area (see also Figs. 1-3). The Lago Basin structural depression corresponds to that crustal sector where the transfer zone is more permeable, channelling deep geothermal fluids; it is envisaged that magmas intrude the shear zone determining the local heat flow increase (after Liotta & Brogi, 2020, modified).

The extensional tectonics framework, active since the Neogene (Trevisan, 1950; Marinelli, 1959; Serri et al., 1993; Carmignani et al., 1994; Westerman et al., 2004; Molli, 2008; Brogi & Liotta, 2008; Barchi, 2010; Liotta et al., 2015; Rossetti et al., 2015; Jolivet et al., 2021) is challenged by Authors who envisaged a Miocene-Pliocene continuous compressional evolution (Bonini et al., 1994; Bonini & Moratti, 1995; Moratti & Bonini, 1998), up to the Pleistocene (Finetti et al., 2001). The Neogene basins are therefore explained as thrust-top basins (Bonini et al., 1999; Finetti et al., 2001) while the normal faults affecting the whole Larderello area can be explained as thermal fractures, consequence of the emplacement into the crust of a still cooling pluton (Finetti, 2006), although the basement has been affecting by HT-metamorphism and high heat flux since the Messinian, at least (Dallmeyer & Liotta, 1998 with references therein).

This general compressional view was reconsidered by Bonini & Sani (2002), who suggested that the predominant compression was punctuated by short-lived extensional periods in the last 9 Ma. In this latter view, the Neogene basins are still interpreted as thrust-top basins related to the activity of out-of-sequence crustal thrusts, but normal faults are accepted to be developed during the tectonic evolution, particularly during Miocene, thinning the crust and lithosphere (Bonini et al., 2014). However, in the Bonini et al. (2014)’s hypothesis, shortening was again active between 7.5 and 3.5 Ma, when magmatism and crustal thrusts coevally developed, determining the exhumation of the Neogene granitoids of Tuscany (Musumeci et al., 2008; Musumeci & Vaselli, 2012; Sani et al., 2016). A tectonic scenario with extension and local compressional events, active since the Pleistocene, was finally proposed by Sani et al. (2016) and Montanari et al. (2017), including, in the latter extensional process, the magmatic bodies underneath the Larderello area. However, a continuous extensional framework is still considered the most suitable explanation to encompass the evolution of the geothermal area in the same context of the inner Northern Apennines and Thyrrenian Basin evolution (to go deeper in this specific issue, e.g., Lazzarotto, 1967; Lazzarotto & Mazzanti, 1978; Batini et al., 1978; Bertini et al., 1991; Baldi et al., 1994; Bertini et al., 2006; Dallmeyer & Liotta, 1998; Brogi et al., 2005; Brogi & Liotta, 2008; Spiess et al., 2021; 2022).

CONCLUSIONS

The Larderello geothermal area has represented and still constitutes a small but fantastic place where all the disciplines of Earth Sciences can be successfully applied to contribute to the understanding of the relationships between geothermal fluid flow and geological structures.

After a long journey in the progression of knowledge, such a relation appears today reasonably defined, at least in its general framework, and can be summarised as follows:

- In present-day reservoirs, fluids are dominantly meteoric and able to flow at significant depths, now reached down to the fractured basement, where their occurrence is mostly highlighted by seismic reflection lines.

- the transfer faults, NNE oriented, are the most favourable to promote vertical permeability and to host fluid flow. Furthermore, intersection between transfer and normal faults again represents an almost vertical permeable and favourable channels.

- the palaeo-fluids documented by fluid inclusions indicate a clear fluid evolution, from the magmatic/contact-metamorphic stage to the hydrothermal stage up to the current state. The first stage likely developed at the level of a palaeo-K-horizon. It implies the tectonic stability of the system, that is framed in the continuous Miocene to Present extensional context, characterised by exhumation and regional uplift.

- The current thermal anomaly is at least active since the Pliocene. This long-lived magma source can again find an explanation in the vertical permeability, promoting a continuous feeding of deep melt.

Nevertheless, scientific and technical open questions are still dominant, such as the possibility of defining and reaching the structural traps where fluids are supposed to be in supercritical conditions, as it is expected within and below the K-horizon depth.