INTRODUCTION

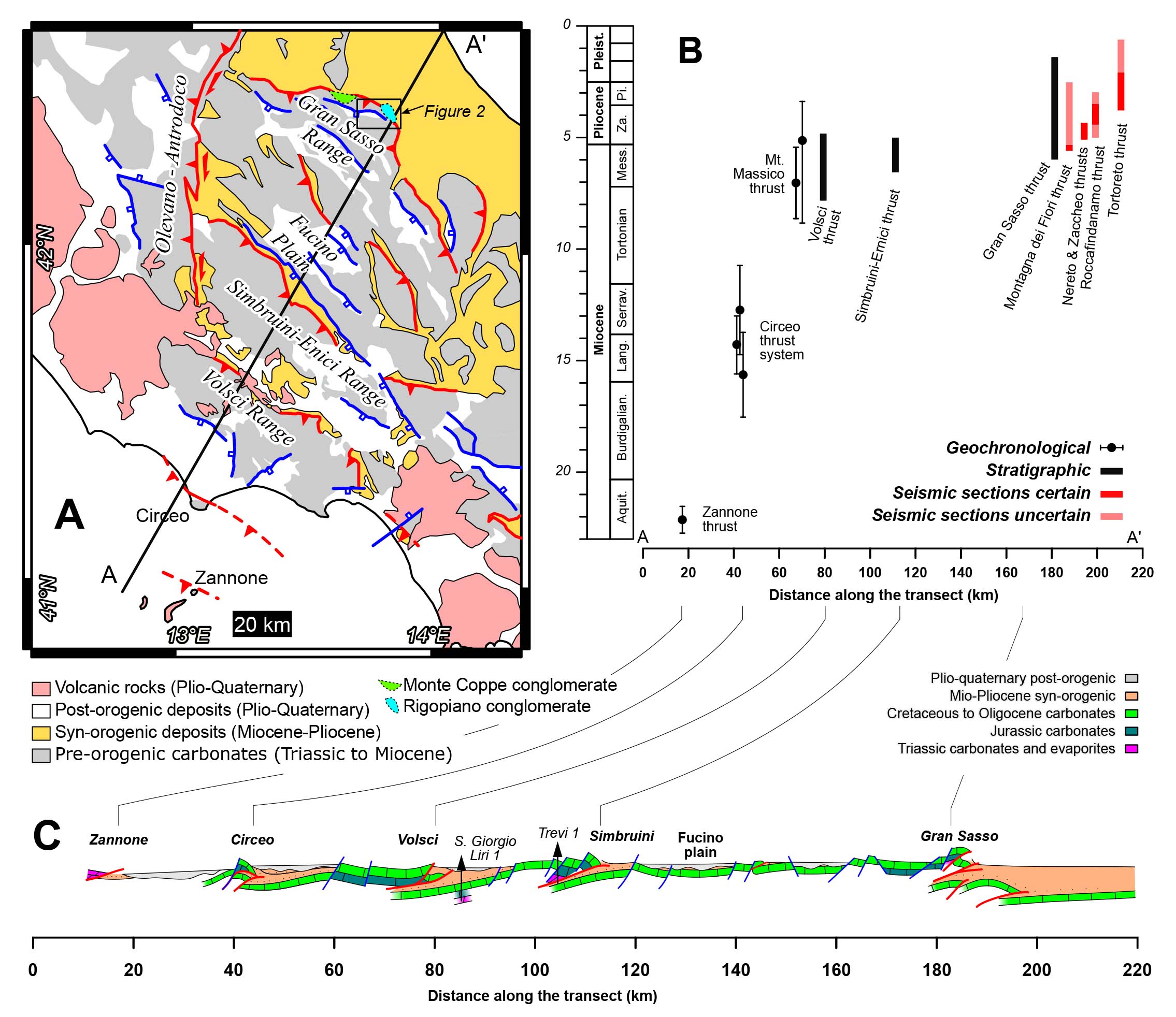

The NE-verging thrust system of the central Apennines consists of five major thrusts developed in a piggy-back sequence: the Zannone, Circeo, Volsci, Simbruini-Ernici, and Gran Sasso thrusts (Fig. 1). The latter forms the mountain front of the central Apennines, and it is defined by a ~100 km long salient, whose central part, the Gran Sasso range, stands out by up to 2000 meters above the adjacent foothills. The range is underlain by the NE-verging Gran Sasso thrust system, and it is bounded to the SW by a set of S- to SW-dipping post-thrusting extensional faults (Fig. 2). Triassic dolostones are the oldest exposed rocks in the hanging wall of the thrust system, whereas Messinian siliciclastic deposits extensively crop out in its footwall (e.g., Ghisetti & Vezzani, 1986; Satolli et al., 2005; Servizio Geologico d’Italia, 2010; Cardello & Doglioni, 2015), making the Gran Sasso thrust one of the exposed thrusts with the largest stratigraphic separation in the Apennines.

- A) Geological scheme of the central Apennines, highlighting the Gran Sasso syn-kinematic conglomerate units. B) SW-NE-trending transect with the ages of major thrusts plotted against the distance along the transect. The dating methods are indicated, and the ages are sourced as follows: Zannone thrust from Curzi et al. (2020); Circeo thrust system from Tavani et al. (2023); Massico Mt. thrust from Smeraglia et al. (2019); Volsci thrust from Cardello et al. (2021); Simbruini-Ernici and Marsica thrusts from Cavinato & De Celles (1999), Fabbri et al. (2023) and Smeraglia et al. (2024); Gran Sasso thrust from this study; and other ages are from Artoni (2007). C) Simplified geological scheme across the central Apennines, with the vertical scale approximately matching the horizontal scale (some depths are exaggerated for clarity). The deep geometry of the Simbruini thrust sheet is constrained by the Trevi 1 well. The deep geometry of the Vosci thrust honours the occurrence of a lateral ramp at the SE termination of the thrust sheet, putting in contact Mesozoic carbonates and Miocene siliciclastic deposits (Figure 8 in Tavani et al., 2021).

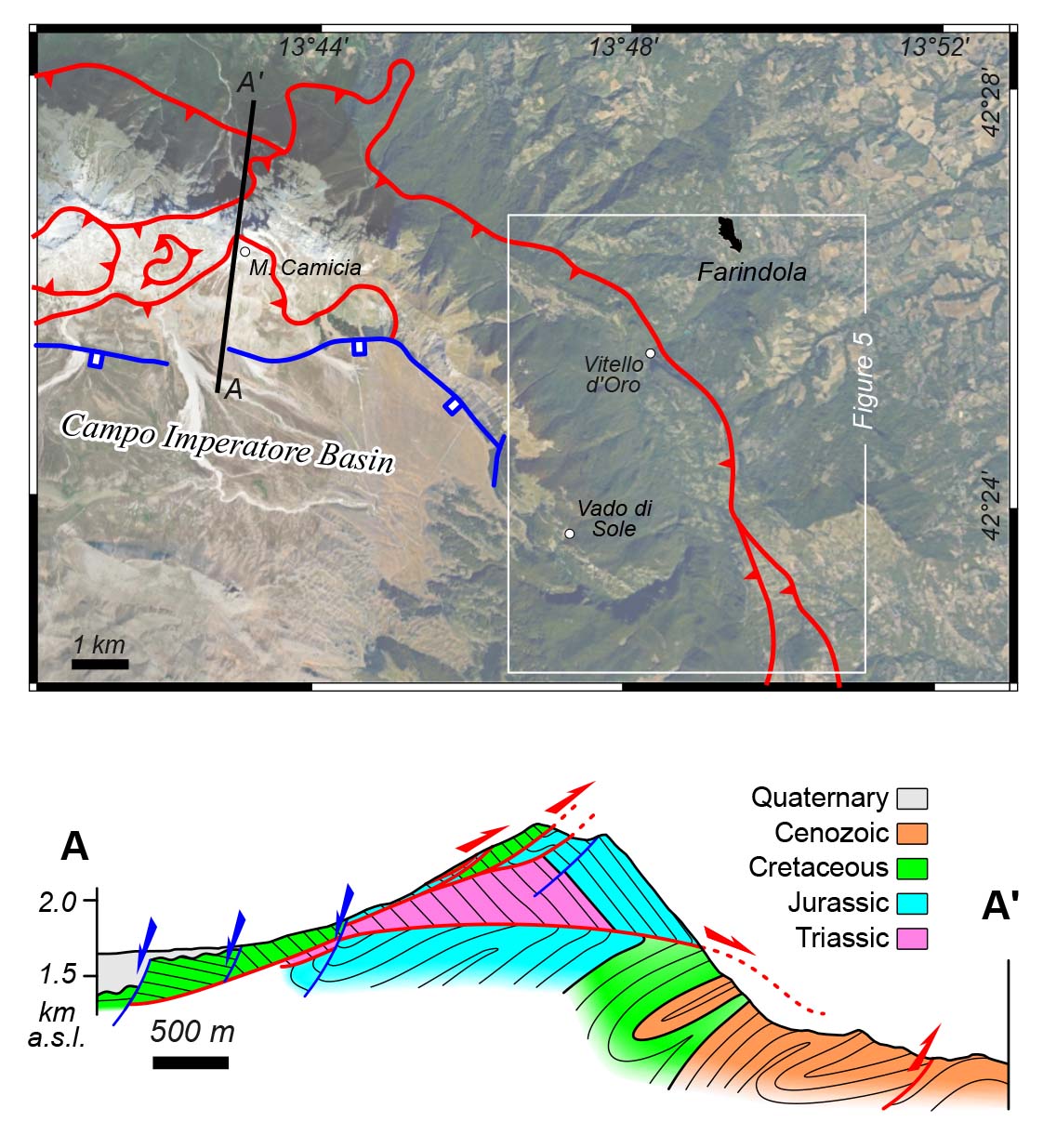

- Google maps orthophoto of the Gran Sasso ridge near Farindola (with main faults indicated) and geological cross-section across the thrust system (after Lucca et al. 2019).

Numerous crustal-scale reconstructions of the Gran Sasso thrust system exist, proposing shortening values spanning from ~ 5 km (e.g., Tozer et al., 2002) up to more than 30 km (e.g., Ghisetti et al., 1993a; Cosentino et al., 2010). The proposed short lifespan of the Gran Sasso thrust, with two thrusting events separated by a quiescent period in less than 2 Myr (e.g., Ghisetti & Vezzani, 1991; Patacca et al., 1992; Cosentino et al., 2010), raises concerns about far-traveled solutions: tens of kilometers in less than two million years would imply shortening rates of cms/yr, which are unusually high for thrust-related structures (e.g., Lacombe & Beaudoin, 2024). However, the uncertainty associated with the age of the Gran Sasso thrusting is high. Despite the onset of thrusting being considered late Messinian by many authors (e.g., Cavinato & De Celles, 1999), the foredeep deposits in the footwall of the thrust show evidence of the occurrence of a submarine ridge in the Gran Sasso area already during the early Messinian (Milli et al., 2007). The end of thrusting is constrained by the ages of two wedge-top units, the Monte Coppe and Rigopiano conglomerates (Ghisetti et al., 1993b), and by the oldest post-kinematic unit, the Arapietra synthem (Servizio Geologico d’Italia, 2010). Nevertheless, the age attribution of these units is rather speculative and/or debated. The rocks of the Arapietra synthem are barren of fossils, and the attribution to the Early Pleistocene is speculative (Servizio Geologico d’Italia, 2010). Concerning the wedge-top units, the Rigopiano and Monte Coppe conglomerates were proposed to form different stratigraphic units with different ages (e.g., Ghisetti et al., 1993b). The age of the Monte Coppe conglomerate is debated: Messinian according to some authors (e.g., Ghisetti et al., 1993b); late Messinian to Early Pliocene according to others (e.g., Cosentino et al., 2010). The Rigopiano conglomerate unit is generally attributed to the Early Pliocene based on its fossil content (e.g., Centamore et al., 1992). Notably, this Lower Pliocene attribution is particularly unclear, being rooted in a personal communication from Dr. M. Manfredini, as cited by Adamoli et al. (1983), which remains unverifiable today. Others (e.g., Vezzani & Ghisetti, 1996) support the same age, basing their assessment on the Early Pliocene age of a pelitic and sandy unit that, according to their interpretation, overlie the Rigopiano conglomerate. However, this interpretation is debated: Bigi et al. (1995) consider the above-mentioned pelitic unit a body interfingered with the conglomerates, whereas Servizio Geologico d’Italia (2005) acknowledge its presence only in limited patches. The few mapped contacts between this unit and the conglomerates allow for conflicting stratigraphic relationships, which we address in this work using modern high-resolution digital elevation models that were not available during the earlier cited surveys.

Based on the age of either the Rigopiano or Monte Coppe conglomerates, the Gran Sasso thrusting during the Early Pliocene is considered an out-of-sequence event after which the thrust activity ceased (e.g., Cavinato & De Celles, 1999). However, it remains unproven whether the wedge-top sediments feature the syn- to post-kinematic boundary, and the hypothesised quiescence is still speculative. To date, the only robust pinpoint for the cessation of thrusting comes from the age of post-thrusting extensional structures in the Gran Sasso range (i.e., switch from compression to extension), which date back to the Late Pleistocene (e.g., Galardini & Galli, 2000). In summary, considering all uncertainties, two possible end-member scenarios can outline the longevity of the Gran Sasso thrust. In the first scenario, thrusting was relatively brief, occurring between the late Messinian and Early Pliocene, making large displacements unlikely, as pointed out by Tozer et al. (2002). Alternatively, thrusting may have extended from early Messinian to the Pleistocene, allowing for displacements of up to a few tens of kilometers. Since the Gran Sasso represents the main thrust of the central Apennines, reducing the uncertainties on its age and duration is crucial for understanding the evolution of the chain, at least in its central portion. To achieve this, we focused on the syn-kinematic Rigopiano conglomerate unit exposed near Farindola village (Fig. 2), which provides the growth stratal record of the Gran Sasso thrust activity. Field surveying aided by a virtual outcrop model (e.g., Basilici et al., 2023), and the application of diverse bio-stratigraphic dating techniques, allowed us to assess the age of these conglomerates and test whether they feature or not the syn- to post-kinematic transition.

GEOLOGICAL SETTING

The central Apennines form a Cenozoic NE-verging thrust and fold belt affected by five major thrusts (Fig. 1). From SW to NE, they are: Zannone, Circeo, Volsci, Simbruini, and Gran Sasso thrusts (e.g., Ghisetti et al., 1993a). These are NE-verging and approximately NW-SE-striking. An exception to this trend is provided by the N-S striking Olevano-Antrodoco thrust, an inherited Jurassic normal fault reactivated as a right-lateral transpressive structure during the Apenninic orogeny (Castellarin et al., 1978). Thrusting in the central Apennines migrated from SW to NE (e.g., Cavinato & De Celles, 1999; Patacca et al., 2008; Cosentino et al., 2010; Tavani et al., 2023) and the Gran Sasso range is the outermost and the youngest of the major thrusts of the central Apennines (Fig. 1). In its footwall, the more external thrust-related anticlines are well-imaged in seismic sections. The integration of seismic lines and explorative wells constrains the onset of thrusting and folding for these structures at the Plio-Pleistocene interval (Artoni, 2007).

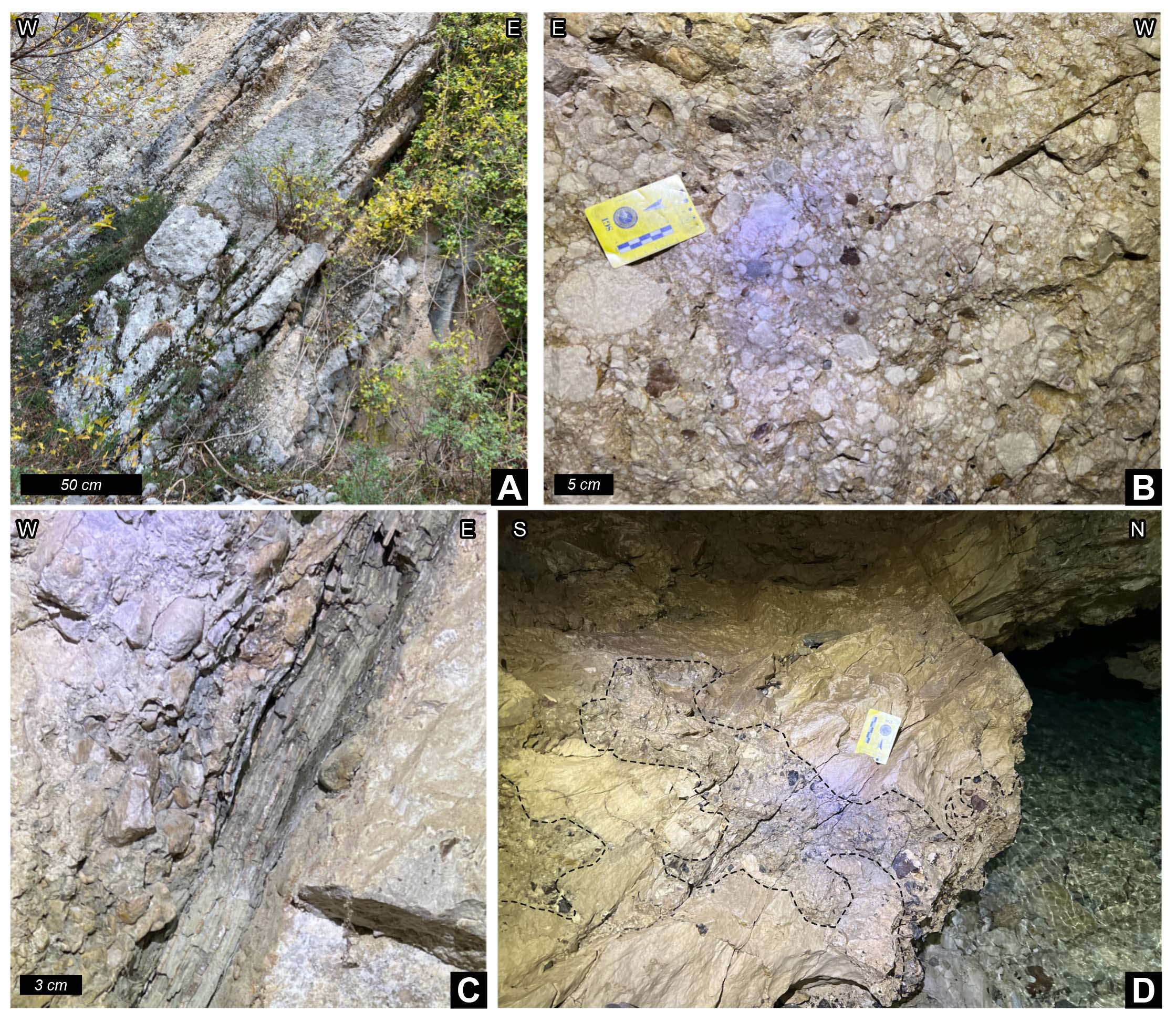

The Gran Sasso range forms a southwest-ward concave salient whose shape is related to both syn-thrusting vertical axis rotations and the occurrence of inherited N-S and E-W striking oblique structures (e.g., Satolli et al., 2005). The vertical axis rotation pattern documented by Satolli et al. (2005) provides evidence for the overall synchronous activity of the entire thrust system from west to east. In a first approximation, the range constitutes the frontal limb of a thrust-related anticline, where Triassic to Cenozoic pre-orogenic carbonates are exposed. This frontal limb is bounded to the southwest by post-thrusting SW-dipping extensional faults and to the northeast by the Gran Sasso thrust (Fig. 2). Both the hanging wall and footwall of the thrust are dissected by splay faults (e.g., Servizio Geologico d’Italia, 2010; Lucca et al., 2019). The Rigopiano conglomerate unit crops out on the eastern side of the range, and it is composed of decimeter- to few meter-thick beds (Fig. 3A) made by carbonate clasts with diameters ranging from centimeters to decimeters (Fig. 3B). Conglomerate beds are alternated with rare cm-thick layers of marls, clays, and varved clays (Fig. 3C), and unconformably rest on top of the underlying units (Fig. 3D).

- Rigopiano conglomerate unit. (A) Outcrop showing W-dipping tens of cm thick conglomerate beds. (B) Details of cm-sized rounded carbonate clasts. (C) Cm-thick W-dipping varve clay. (D) Photos showing patches of the Rigopiano conglomerate (highlighted by dashed lines) unconformably resting on top of south-dipping strata of the Monte Fiore calcarenites in the western portion of the hydraulic tunnel.

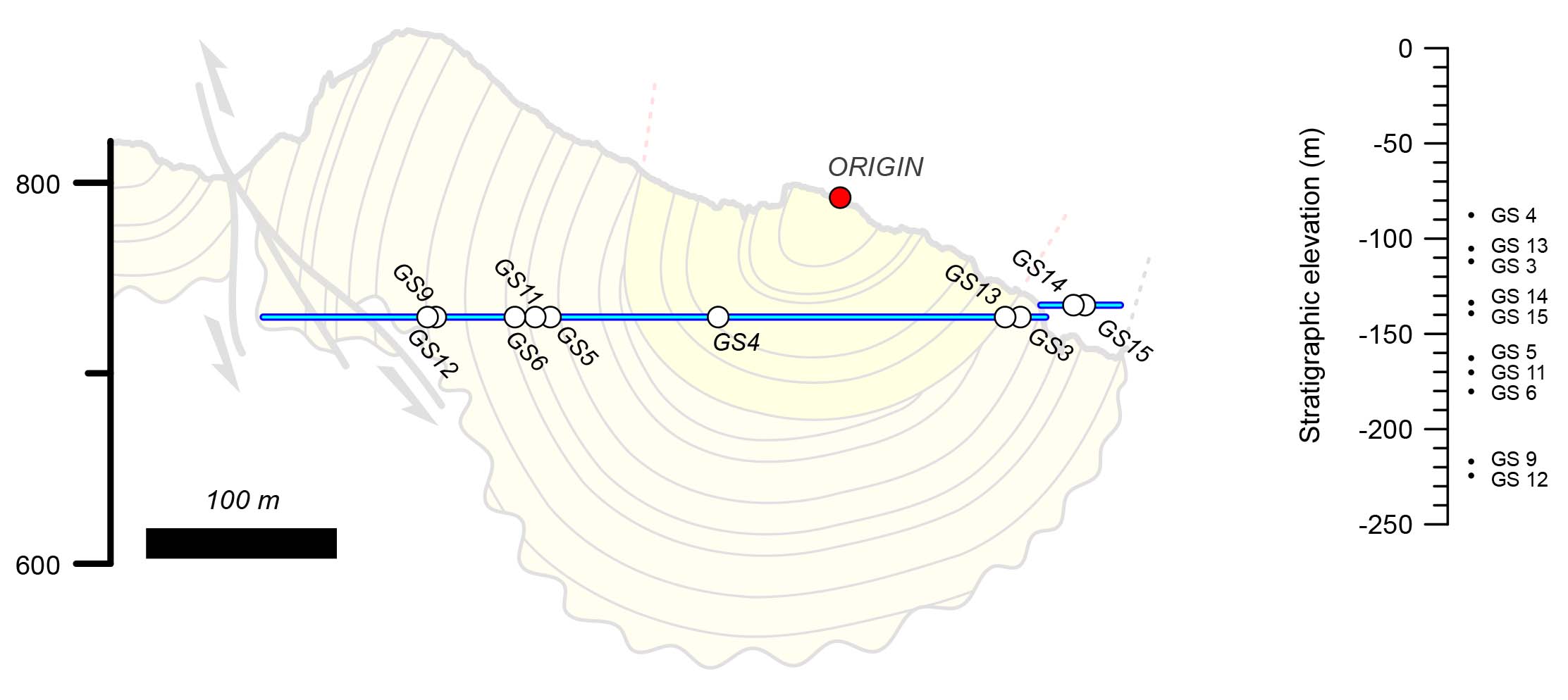

Our work focuses on the area near the Farindola village (Fig. 2), along the N-S striking segment of the Gran Sasso thrust, named Mt. Picca thrust by Ghisetti and Vezzani (1997). There, the Rigopiano conglomerate is deformed by a set of tight folds, one of which is crossed by two drainage tunnels. Using the data and methods illustrated in Figure 4, we produce the geological maps of Figures 5 and 6 and two geological cross-sections, which serve to accurately locate the samples used for biostratigraphic dating.

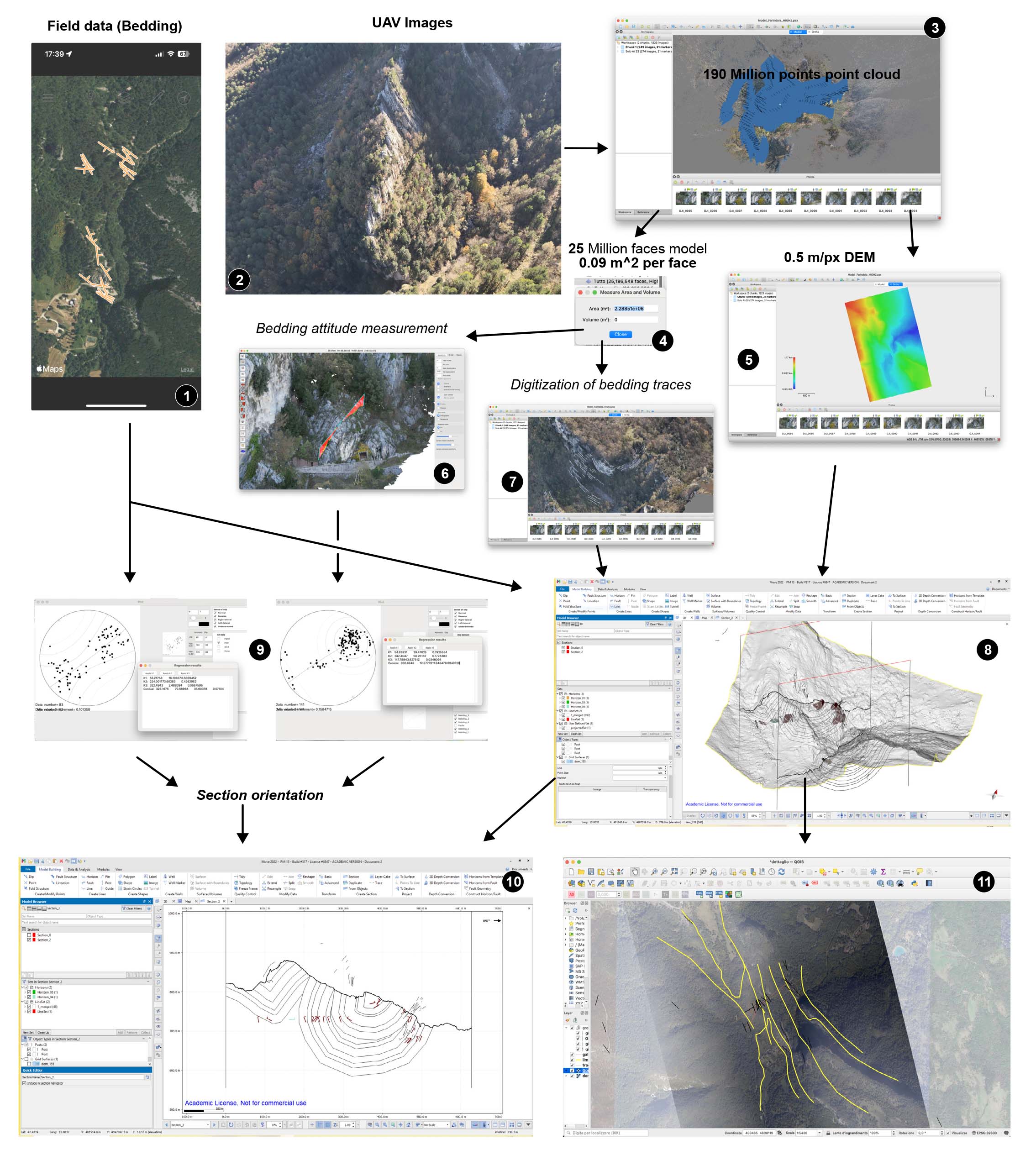

- Scheme illustrating the workflow used to build the geological cross sections and the geological map of Figure 6, with black circles indicating each step mentioned in the methods section (see text for details).

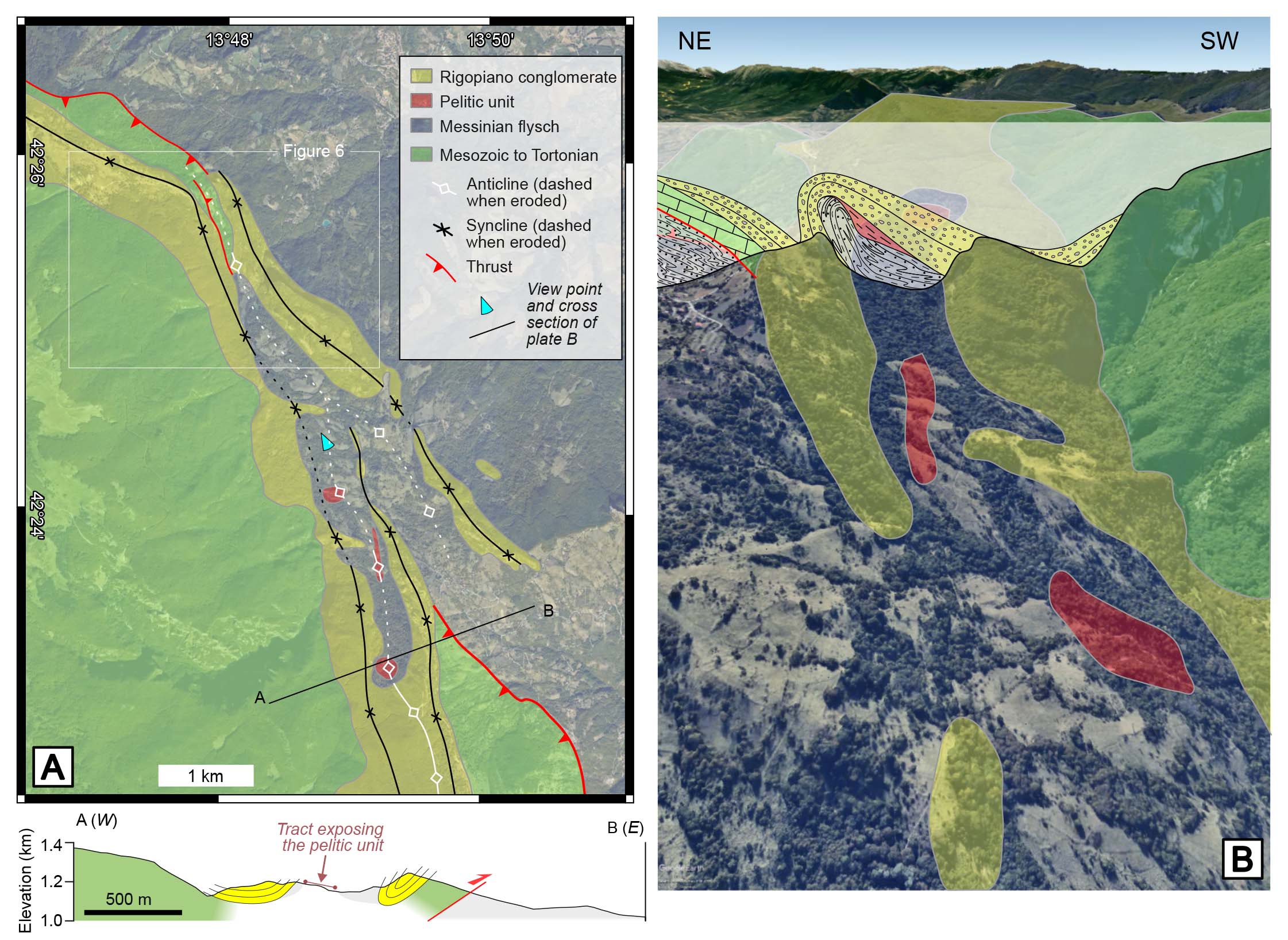

- (A) Simplified geological map of the Farindola area (after Bigi et al., 1995; Servizio Geologico D’Italia, 2005), with (B) interpreted view in Google Earth. The cross-section in B shows the reconstructed units above the topography. (C) Uninterpreted cross-section (trace in A) showing that the tract exposing the pelitic unit lies between two synclines cored by the Rigopiano conglomerate and is therefore stratigraphically underlying it.

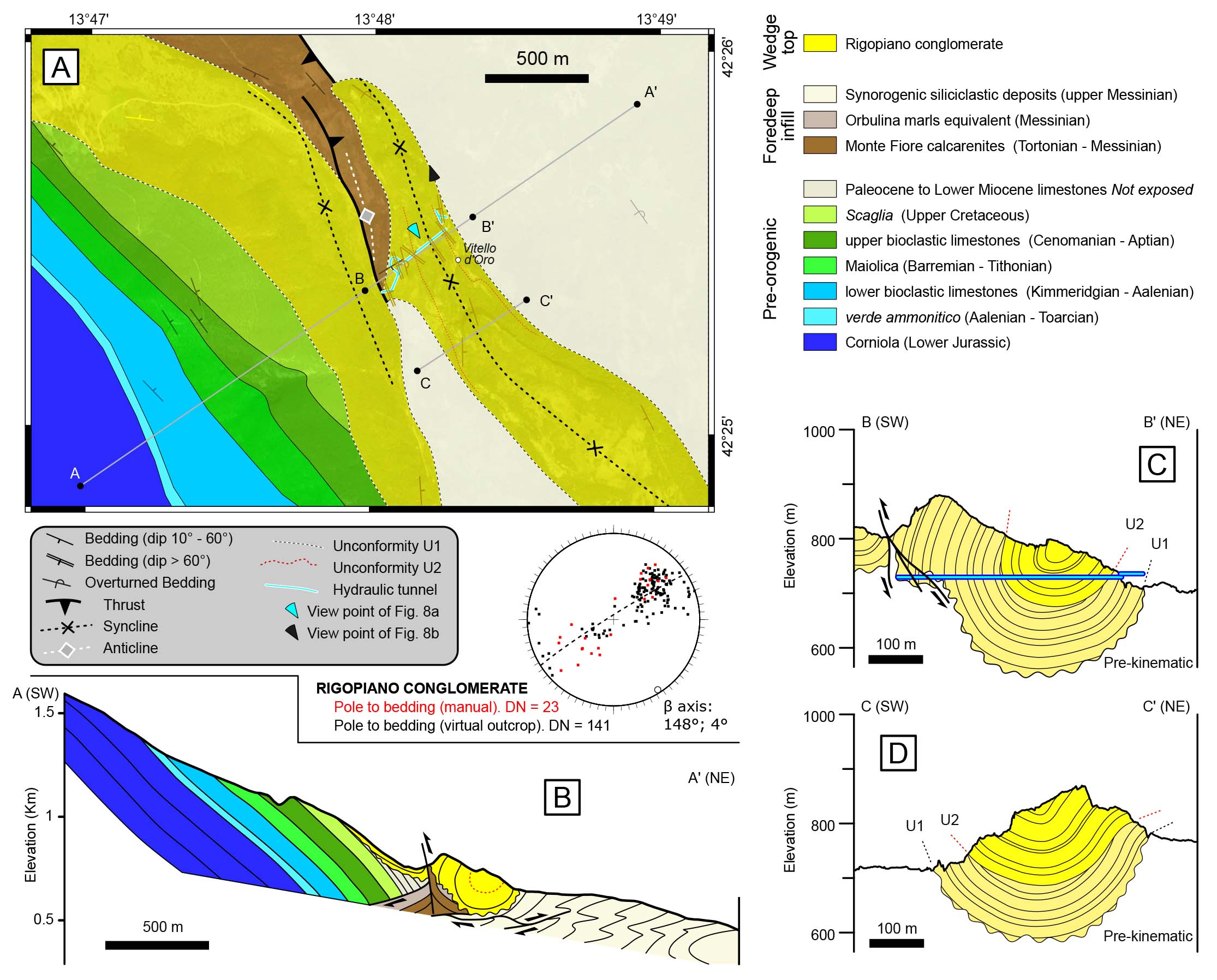

- (A) Geological map of the study area (partly adapted from Bigi et al., 1995), with stereoplot of manually- and digitally-measured (i.e., VOM-measured) bedding data, and β axis of digitally measured bedding. Bedding symbols are colored according to the corresponding unit. (B) Cross section across the study area. (C) and (D) detailed cross sections across the frontal syncline.

DATA AND METHODS

Geological surveying

The first step of our study involved remapping the synclines and anticlines in the Farindola area. To achieve this, we integrated our field surveys with previously published geological maps (Bigi et al., 1995; Vezzani & Ghisetti, 1996; Servizio Geologico d’Italia, 2005), along with the high-resolution DEM (<5 m) recently available on Google Earth. We then focused on the area around the Vitello d’Oro waterfall (Fig. 2), where we applied a multi-disciplinary approach to construct a detailed geological map and cross sections. This approach combined traditional field data collection and analysis with remotely sensed data (Fig. 4). We collected field data (bedding and faults) using the FieldMove application on multiplatform devices, together with a classical compass for rapid quality checks (Step 1 in Fig. 4). We have georeferenced the collected FieldMove data in terms of latitude and longitude but not elevation. We collected a second set of bedding data within a approximately 0.5 km sub-horizontal tunnel (the larger of the two tunnels). There, we measured the distance from the entrance with a tape, and then, knowing the attitude of the tunnel trace, we transformed it into latitude and longitude. For this second set of data, we have set the elevation to that of the tunnel’s entrance.

We have collected a total of 947 georeferenced photos (Step 2 in Fig. 4) using two drones (a DJI Air 2S and a DJI Mavic 3T) and subsequently processed using the SfM-MVS technique (Step 3 in Fig. 4) (e.g., James & Robson, 2012). The processing led to the creation of a georeferenced textured 3D mesh model of 25M triangles over a surface of 2.28x106 m² (Step 4 in Fig. 4) (a low-resolution model of the study area is available for viewing at https://skfb.ly/oVzyp), and a DEM with a resolution downscaled to 0.5 meters per pixel (Step 5 in Fig. 4) to be later imported into 3DMove. Georeferencing through drone image geotags (EXIF data for external georeferencing) is a common practice that typically results in positional errors of a few meters. These errors are generally negligible when camera positions are spaced over several hundreds of meters, preserving the overall scaling and orientation to the geographic north (Corradetti et al., 2022), thus not affecting the internal geometry of the model or the quality of the extracted data (Menegoni et al., 2019). We have used the 3D textured mesh to extract bedding orientation data from inaccessible areas using the OpenPlot software (Step 6 in Fig. 4) (Tavani et al., 2024), while we have digitised 3D bedding traces also in Metashape (Step 7 in Fig. 4). We have imported the Digital Elevation Model (DEM), the field-collected bedding data, and the digitised traces into 3DMove software (Step 8 in Fig. 4). We have draped data collected at the surface over the DEM to align elevations. We have obtained the cylindricity direction - or β axis of the π best-fit plane - from the bedding orientation data (Step 9 in Fig. 4) (e.g., Cawood et al., 2022) and eventually we have used it to define the proper direction of the cross-section planes in the 3DMove (Step 10 in Fig. 4). Here, we have projected all data within 260 m distance from each cross-section perpendicularly and we have used them for the construction of two geological sections. Finally, in 3DMove, we have traced geological boundaries and have exported them into QGIS (Step 11 in Fig. 4).

Biostratigraphic dating

We sampled ten clay (inter-) layers from the Rigopiano conglomerate for bio-stratigraphic analysis (Table 1). We have collected samples inside the two tunnels, and we have determined their position in the stratigraphic succession with a resolution of less than a few meters. Specifically, we have used six layers for palynological analysis; we have used nine layers for foraminifera and ostracods analysis; and nine for calcareous nannoplankton analysis.

| Layer | Pollen analisys | Foraminifera & Ostracods | Calcareous nannofossils | Aspect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollen | Non-pollen | ||||

| GS 3 | Pinus and Betula | Arcella vulgaris Ehrenberg | BARREN | REWORKED Oligo-Miocene | Non varved |

| GS 4 | Pinus and Tsuga with rare Ulmus and Carpinus | BARREN | REWORKED Oligo-Miocene | Non varved | |

| GS 5 | BARREN | REWORKED | REWORKED Oligo-Miocene | Non varved | |

| GS 6 | BARREN | Non varved | |||

| GS 9 | BARREN | BARREN | REWORKED Oligo-Miocene | Non varved | |

| GS 11 | BARREN | BARREN | REWORKED Oligo-Miocene | Non varved | |

| GS 12 | BARREN | REWORKED Oligo-Miocene | Non varved | ||

| GS 13 | BARREN | BARREN | Varved | ||

| GS 14 | BARREN | Helicosphaera sellii | Non varved | ||

| GS 15 | BARREN | REWORKED Oligo-Miocene | Non varved | ||

For pollen extraction, we have treated sediments with chemical and physical procedures (for details, see Di Lorenzo et al., 2023); we have mounted slides in glycerin and we have analysed them under a light microscope at 500X and 1000X magnification.

For foraminifera and ostracods analysis, we have disaggregated the samples in hydrogen peroxide solution (5%), sieved with a 0.63 mm mesh sieve and dried. We have observed five grams of each dried, sieved sample under the stereomicroscope (14–150) to handpick and identify the microfossils.

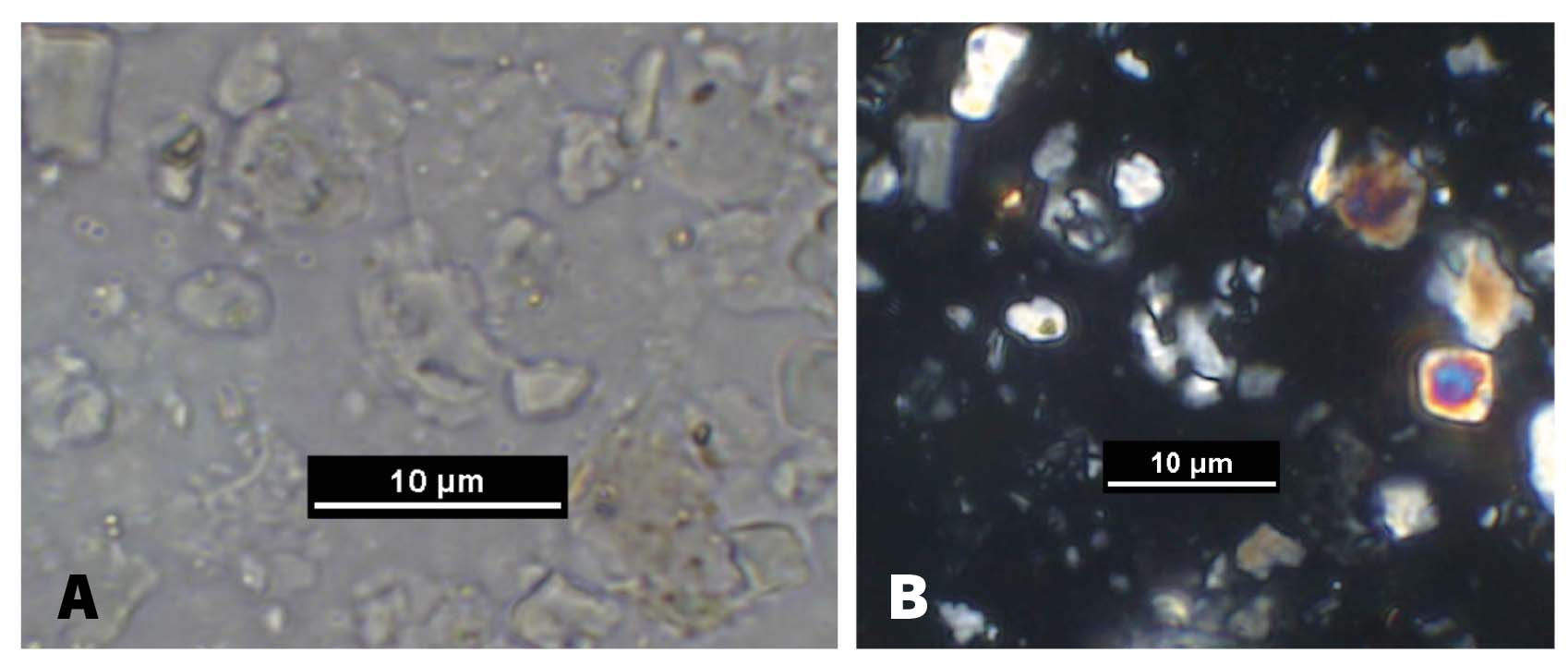

We have prepared the calcareous nannoplankton samples as standard smear slides (Bown & Young, 1998) and we have analysed them with a polarised light microscope at x1000 magnification. We have evaluated the abundance of in situ taxa and reworked taxa by semi-quantitative analyses. We have identified calcareous nannofossil taxa biozones following the taxonomic concepts and biozonal scheme recently proposed by Di Stefano et al. (2023).

RESULTS

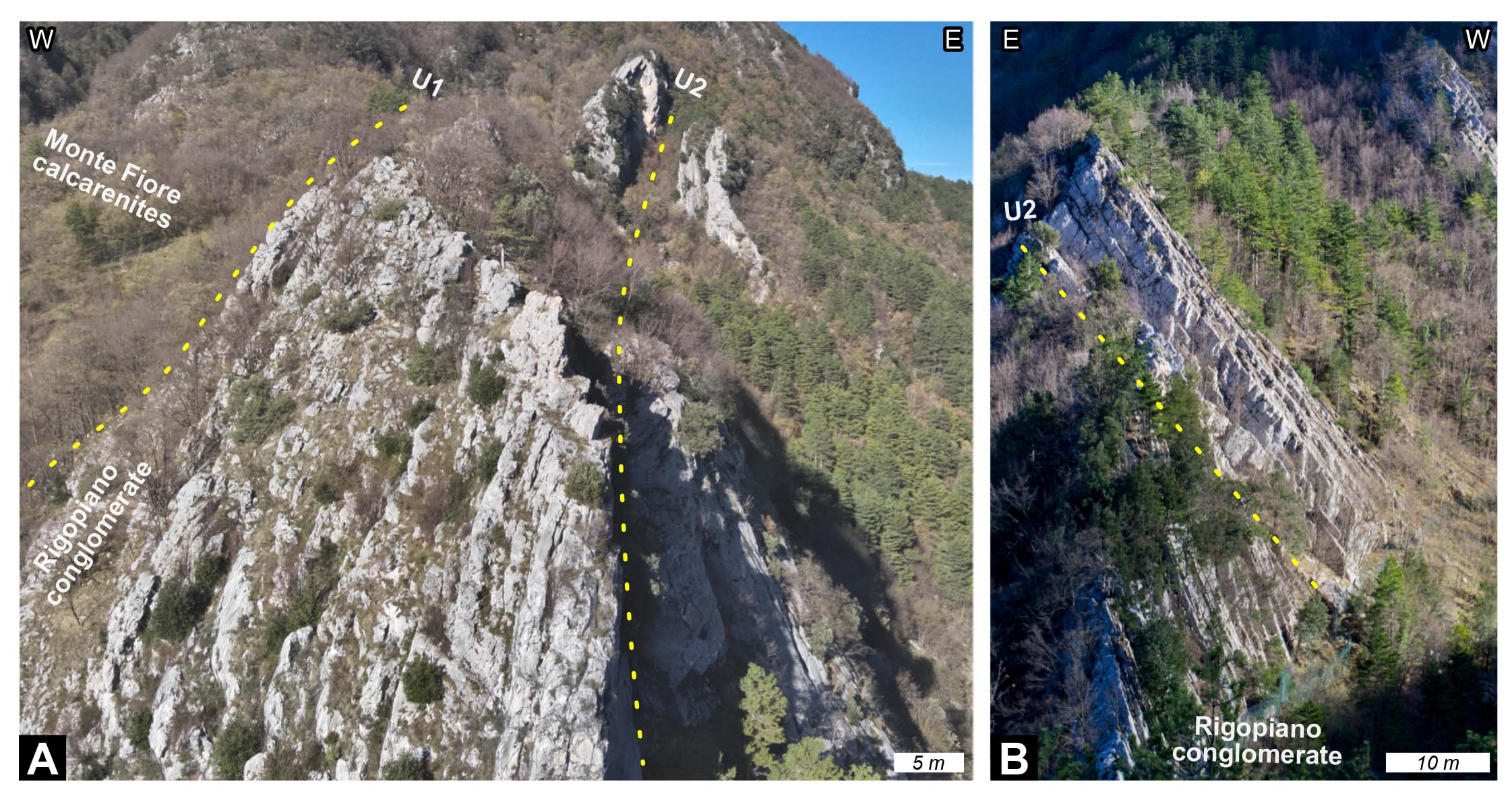

The study area consists of a NE-dipping homocline of Jurassic to Paleocene pre-orogenic strata, thrust on top of a slice of Lower Miocene carbonates and hemipelagites, which is in turn thrust on top of the overturned Messinian siliciclastic rocks. These two recognised thrusts form part of the Gran Sasso thrust system, unconformably covered by the Rigopiano conglomerate (Figs. 5, 6). In detail, the Rigopiano conglomerate in the Farindola area is deformed by a system of NNW-SSE trending folds (Fig. 5), and it is primarily preserved within the cores of synclines, whereas the cores of anticlines expose both pre-thrust units and patches of a pelitic unit dated to the Early Pliocene by Vezzani & Ghisetti (1996) (displayed in brown in Figure 5). Although these authors suggest that this pelitic unit is stratigraphically above the Rigopiano conglomerate, the structural architecture shown in Figure 5 clearly demonstrates that in the study area the Lower Pliocene pelitic unit is older than the Rigopiano conglomerate. In the Vitello D’Oro waterfall area, the Rigopiano conglomerate is deformed into two synclines separated by a tight faulted anticline, cored by Miocene carbonates and hemipelagites to the NW and by the Messinian siliciclastic rocks to the SE. The frontal (i.e., north-eastern) syncline laterally evolves from tight to the NW (Fig. 6C) to open to the SE (Fig. 6D). In the NW section (Fig. 6C), strata of the inner (i.e., south-western) limb are overturned. This limb there is affected by a system of backthrusts, which are found in the western tract of the longest tunnel (Fig. 7), and that, in our view, connect with the low-displacement (i.e., a few tens of meters) backthrust cropping out at the surface (Fig. 6A). Notably, this backthrust should be regarded as an accommodation structure developed within the core of the tight anticline in between the two synclines during folding. Because of the backthrust, the anticline is almost obscured in the section shown in Figure 6C. In the same western part of the tunnel, the discordant contact between the Rigopiano conglomerate and the underlying Monte Fiore calcarenites is observed (Fig. 3D), and the SE-dipping bedding in Figure 6A refers to the Monte Fiore calcarenites. Two unconformity surfaces with opposite angles (i.e., one wedging toward the west and the other toward the east) crop out on the opposite limbs of the frontal syncline (Figs. 6, 8). Following the digitised traces on the Virtual Outcrop Model and the collected bedding data, as illustrated in the methods section, these two surfaces can be joined into a unique one (labeled U2 in Figure 6), depicting a growth unconformity that developed coevally with the growth of the syncline. The lower part of the Rigopiano conglomerate is discordant onto the substratum, while the upper part is partly discordant onto the lower one. We project the position of the samples collected in the drainage tunnels onto the cross section of Figure 6C and compute their stratigraphic elevation with respect to the uppermost exposed layer (Fig. 9).

- Photos of WSW-verging thrust cropping out in the western tract of the drainage tunnel (with overturned W-dipping strata), with plot of faults measured there.

- Photos of the unconformity (indicated by the yellow dotted line) between the pre-kinematic Monte Fiore calcarenites and the Rigopiano conglomerate (U1) and within the Rigopiano conglomerate (U2) on the western (A) and eastern (B) limbs of the frontal syncline. The bedding is steeply- dipping above U2 and in B, overturned between U1 and U2 in A.

- Location of samples within the hydraulic tunnels and corresponding stratigraphic elevation.

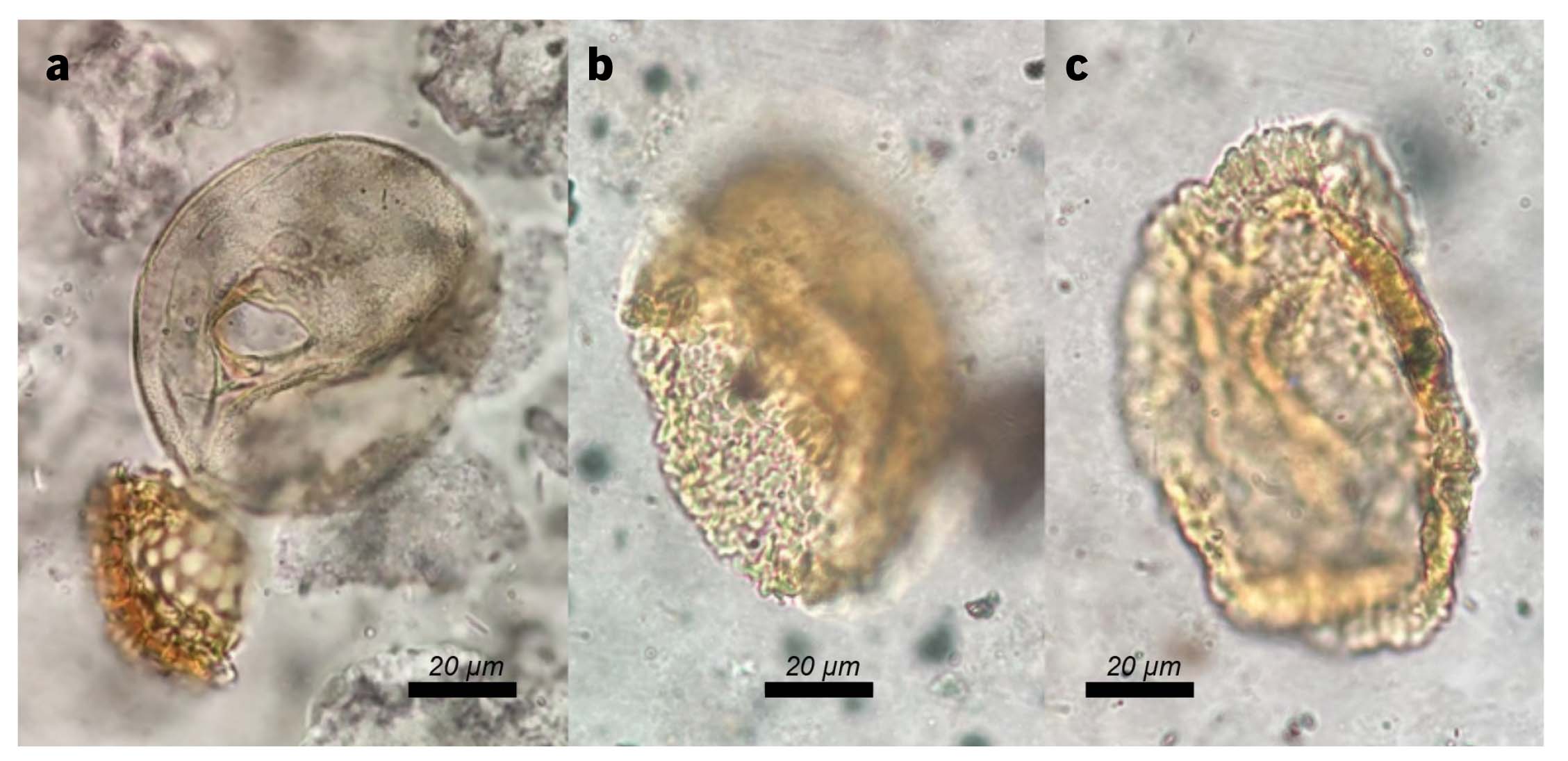

The samples collected for foraminifera and ostracods analysis were all barren. Samples from four out of six layers were barren in palynomorphs. In the sample from layer GS3, several specimens of the thecamoeba Arcella vulgaris Ehrenberg (Siemensma, 2019) were found (Fig. 10a), together with a few pollen grains of Pinus and Betula and some reworked dinoflagellate cysts. Highly altered but recognizable pollen are present in the sample from layer GS4. Tsuga is the main tree taxon (Fig. 10b-c) next to Pinus and rare Ulmus and Carpinus. In the same sample, some herbaceous plants, including Asteraceae and Poaceae, are also observed, along with the significant presence of reworked dinoflagellate cysts. Calcareous nannoplankton samples from layer GS6 were barren, containing only inorganic microcrystals and organic matter. Samples from the other seven layers (GS3, GS4, GS5, GS9, GS11, GS12, GS15) consist exclusively of a mélange of common to rare Cretaceous and Oligo-Miocene reworked taxa and abundant inorganic microcrystals. The only sample that allowed a chrono-stratigraphic attribution is from layer GS14. The basic structure of this sample is comparable to the previous ones, with common to rare Cretaceous and Oligo-Miocene reworked taxa and abundant inorganic microcrystals, but it is distinguished by the presence of rare Helicosphaera sellii (Fig. 11) (First Common Occurrence 4.62 Ma – Last Occurrence 1.26 Ma). From the point of view of calcareous nannoplankton, the sedimentary environment is comparable to a basin characterised by extremely shallow bathymetry and abundant continental runoff (Bonomo et al., 2016).

- Examples of pollen and non-pollen palynomorphs. (A) Arcella vulgaris Ehrenberg from sample in layer GS3; B-C) two Tsuga specimens from sample in layer GS4.

- Helicosphaera sellii in sample from layer GS14. (A) cross and (B) parallel nicols.

DISCUSSION

The Rigopiano conglomerate unit unconformably overlies strata folded during the activity of the Gran Sasso thrust, but it is also tightly folded and features a growth unconformity (U2 in Figure 6; Fig. 8), coherent with its syn-kinematic character. However, the Rigopiano conglomerate does not include the syn- to post-kinematic transition, so it can be interpreted as a late thrusting unit, but the cessation of the Gran Sasso thrust activity postdates its deposition.

The geological map in Figure 5 provides a clue on the age of the Rigopiano conglomerate. The pelitic and sandy unit, which Vezzani & Ghisetti (1996) date to the Early Pliocene based on the presence of “a considerable number of benthic foraminifera, along with echinoid spines and lamellibranch remains,” crops out evidently in the core of anticlines flanking synclines cored by the Rigopiano conglomerate.

Biostratigraphic analyses provided key insights into both the depositional environment and the age of the Rigopiano conglomerate. The depositional environment is interpreted as continental to shallow marine, based on the following evidence: (i) the presence of the thecamoeba Arcella vulgaris Ehrenberg (Fig. 10a), indicative of stagnant freshwaters or wet soils; (ii) the occurrence of varved clay layers, pointing to a continental lacustrine environment (Fig. 3C); (iii) the preferences of Helicosphaera genus to the environments influenced by riverine discharge (low salinity and high terrigenous input) (e.g., Dimiza & Triantaphyllou, 2014). Our findings contrast with earlier literature reports of Pliocene marine planktic fossils in the Rigopiano conglomerate. To address this discrepancy, we have critically reviewed the existing literature to evaluate whether these marine planktic forms could be re-sedimented. However, the original samples are unavailable, and no reliable photographic documentation exists. In the absence of verifiable data, we conclude that the Rigopiano conglomerate represents a continental to shallow-marine deposit. This conclusion is further supported by geochemical analyses from Lucca et al. (2019) in the Monte Camicia area (Fig. 2), located 5 km to the northwest, in the hanging wall of the Gran Sasso thrust, which document the transition from marine to subaerial conditions during the late stage of the development of the Gran Sasso thrust system.

Regarding the age, the most recent and significant element, found in sample GS4, is Tsuga (Fig. 10c-d), a mountain tree extinct from Europe, nowadays thriving in temperate zones of North America, China, Japan, and the Himalayas. It is a micro-mesothermic conifer, demanding cool temperatures and high atmospheric humidity (at least 1000 mm/year, annual temperatures 0-12°; Thompson et al., 1999), which was widespread in the mountain belt of the Apennines during Pliocene and Early Pleistocene time (e.g., Bertini, 2010; Fusco, 2010; Russo Ermolli & Bertini, 2014; Bertini & Combourieu-Nebout, 2023). Its last remarkable expansion is recorded shortly before the Jaramillo subchron in northern Italy (Muttoni et al., 2003; Ravazzi et al., 2005) or during the Jaramillo in central Italy (Bertini, 2000). Since then, its presence became more and more sporadic, the last occurrence being recorded during MIS 13 in Molise (Orain et al., 2013). Based on: (i) the significant presence of Tsuga in sample GS4 and (ii) the absence in all the analysed samples, including GS4, of other typical subtropical taxa recorded in the Pliocene, such as Taxodium, Cathaya and Cedrus (Bertini, 2000, 2001, 2010), the upper portion of the Rigopiano conglomerate (where sample GS4 is located, Fig. 9) can likely be constrained to the very Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene. Nannoplankton analysis agrees with this conclusion, as indicated by the occurrence, in sample GS14 (stratigraphically positioned 20-30 meters below sample GS4), of rare Helicosphaera sellii specimens well comparable to Pliocene morphotype (Fig. 11 - large central openings and coccolith size > 10 μm) (First Common Occurrence 4.62 Ma – Last Occurrence 1.26 Ma).

In summary, considering that the Rigopiano conglomerate is clearly a late thrusting unit not including the syn- to post-kinematic transition, the cessation of the Gran Sasso thrust activity can be dated to the very Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene interval. According to available literature data, an early Messinian onset of thrusting in the Gran Sasso area (e.g., Bigi et al., 2009) can be constrained by the existence of a ridge, in our scenario of tectonic origin, during the deposition of the lower Messinian portion of the siliciclastic deposits, which acted as a barrier to turbidite flows from the north (Milli et al., 2007). Owing to these ages (onset in early Messinian and cessation in Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene times), the duration of thrusting is thus between 4 and 5 Myr (instead of 2 Myr hypothesised in the past). However, even with these values, a displacement above 30 km (e.g., Ghisetti et al., 1993a; Cosentino et al., 2010) remains problematic. Based on our new age constraints, such a displacement would imply a slip rate of 7–9 mm/yr for the Gran Sasso thrust, substantially higher than the 0.5–4 mm/yr slip rates calculated for the Apennine thrusts (e.g., Gunderson et al., 2013; Maesano et al., 2013; Carboni et al., 2019; Panara et al., 2021) and the long-term slip rates documented in other thrust belts (e.g., 3.5 mm/yr in the Southern Alps, Livio et al., 2009; 2 mm/yr in the Pyrenees, Burbank et al., 1992; 2 mm/yr in the Qilian Shan, Hetzel et al., 2019).

CONCLUSIONS

We have reassessed the age, depositional setting, and structural significance of the latest growth strata of the Gran Sasso thrust, i.e., the Rigopiano conglomerate. These growth strata were deposited in Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene time, in a continental to shallow marine environment during the growth of the Gran Sasso range. Our study represents a significant advancement in the understanding of the Gran Sasso thrust age and, by extension, the thrust system of the central Apennines. The revised Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene age assigned to the Rigopiano conglomerate suggests that activity along the Gran Sasso thrust persisted much longer than previously thought, challenging the concept of out-of-sequence thrusting in the central Apennines.