INTRODUCTION

Triassic dinosaur and dinosauromorph footprints, have been the focus of ichnological research by numerous authors for a long time (Hitchcock, 1845, 1858; Lull, 1904, 1953; Huene, 1941; Peabody, 1948; Bock, 1952; Heller, 1952; Baird, 1957; Kuhn, 1958b; Haubold, 1967, 1971b, 1986, 1999; Demathieu 1970, 1989; Ellenberger, 1970, 1972; Demathieu & Gand, 1972; Olsen & Baird, 1986; Weems, 1987, 1993, 2018; Hunt et al., 1989, 2000; Gierliński & Ahlberg, 1994; Fraser & Olsen, 1996; Lockley et al., 1996, 2000, 2001, 2006a,b; Thulborn, 1998; Gatesy et al., 1999; Courel & Demathieu, 2000; Haubold & Klein, 2000, 2002; Ptaszyński, 2000; Olsen & Rainforth, 2001; Nicosia & Loi, 2003; Gand & Demathieu, 2005; Lucas & Sullivan, 2006; Marsicano, 2006; D’Orazi Porchetti et al., 2008; Lucas et al., 2010; Brusatte et al., 2011; Niedźwiedzki, 2011; Bernardi et al., 2013; Fichter & Kunz, 2013; Meyer et al., 2013; Niedźwiedzki et al., 2013; Xing et al., 2013; Lallensack et al., 2017; Zouheir et al., 2020; Romilio et al. 2021; see Klein & Lucas, 2021 and Lucas et al., 2025 for overview), ut still encompass some unsolved problems and open questions. These concern ichnotaxonomy as well as their relationship to different dinosaur groups, and, moreover, in some cases doubts remain of their true dinosaurian origin. In particular, mesaxonic tridactyl footprints from the Triassic have a uniform principal morphology and therefore are difficult to differentiate and determine at the ichnospecies level (see also Lockley, 1998, 2009). Often, they can only be assigned to a broader plexus. Their dinosaur attribution needs to keep in mind that the tridactyl pes of basal dinosauriform ancestors was well consolidated and subsequently did not undergo substantial evolutionary changes that potentially were preserved in the footprints. So, how to identify a theropod or ornithischian dinosaur track and distinguish it from that of a basal dinosauriform, for example a silesaurid? In advance we have to say that dinosaur diagnostic data are scarcely available from preserved tridactyl tracks or they are based on parts of the skeleton other than the pes. The situation is slightly better when looking at the Triassic sauropodomorph track record. Footprints are tetradactyl to pentadactyl with diagnostic features regarding posture, size and orientation of digits and claw traces. In the following we give an overview of selected dinosauriform-dinosaur footprints from the Triassic, interpreting trackmakers and outlining significant steps in the evolution of the locomotor apparatus.

FOOTPRINT RECORD

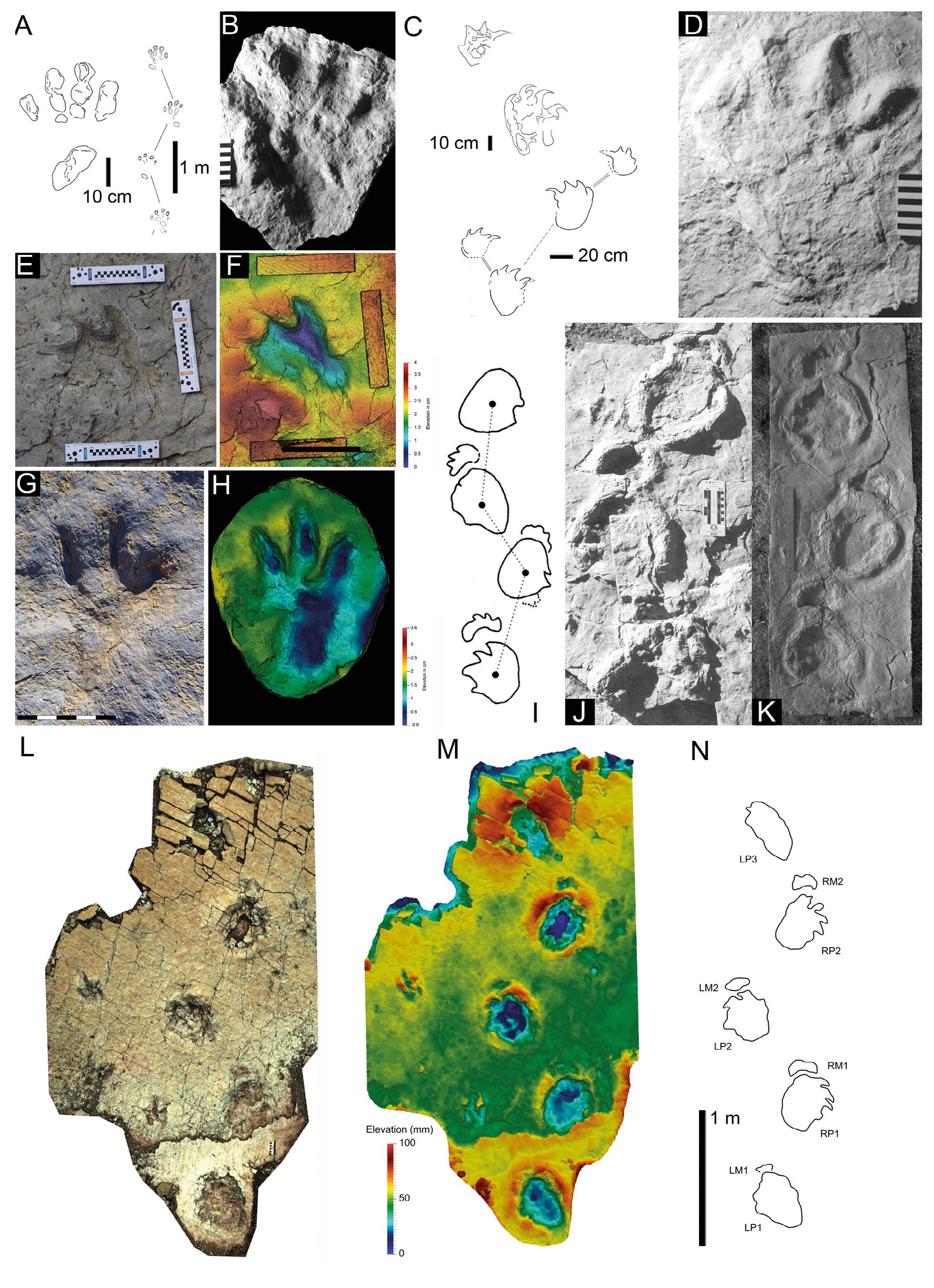

Rotodactylus Peabody 1948-tracking early dinosauromorphs

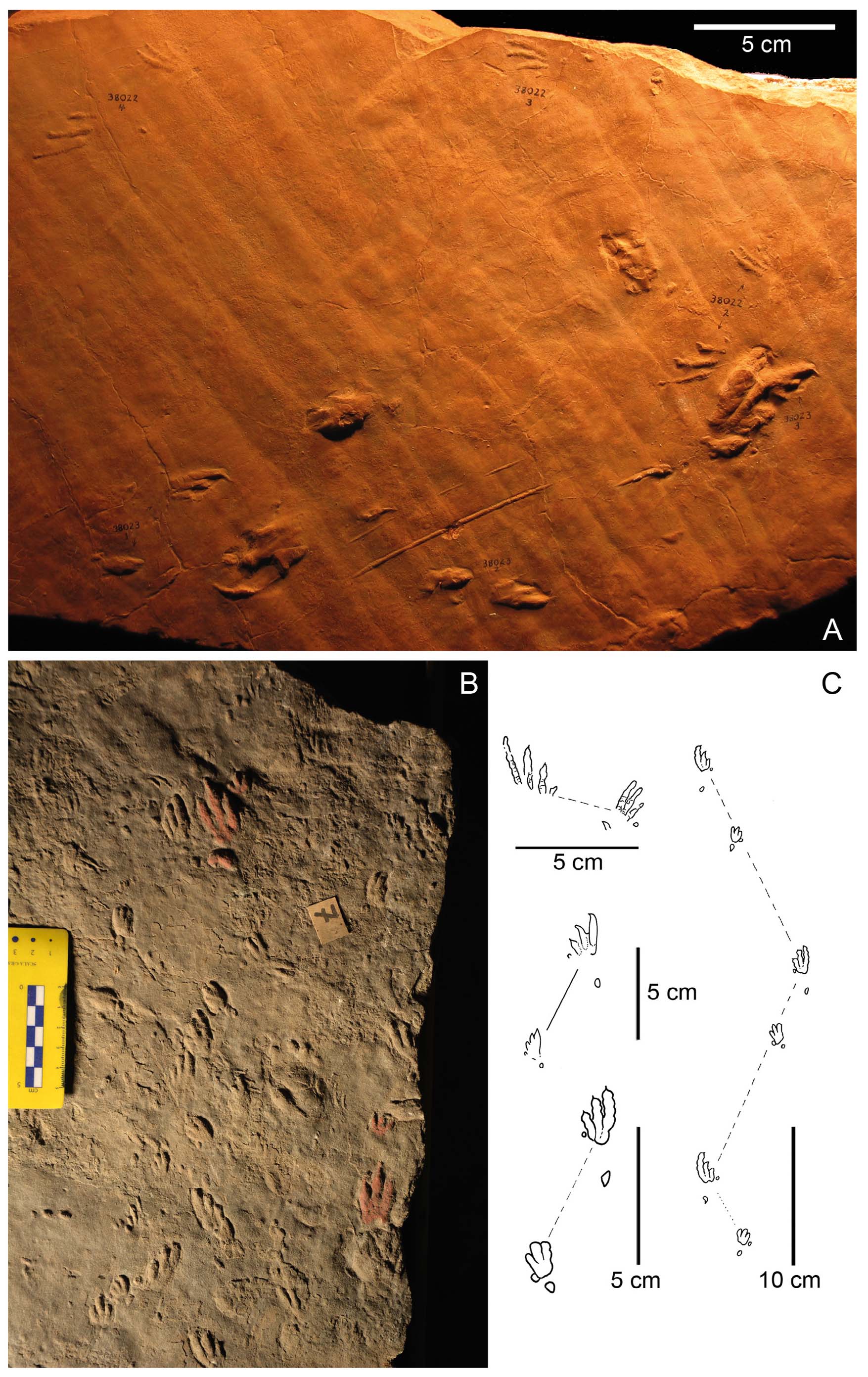

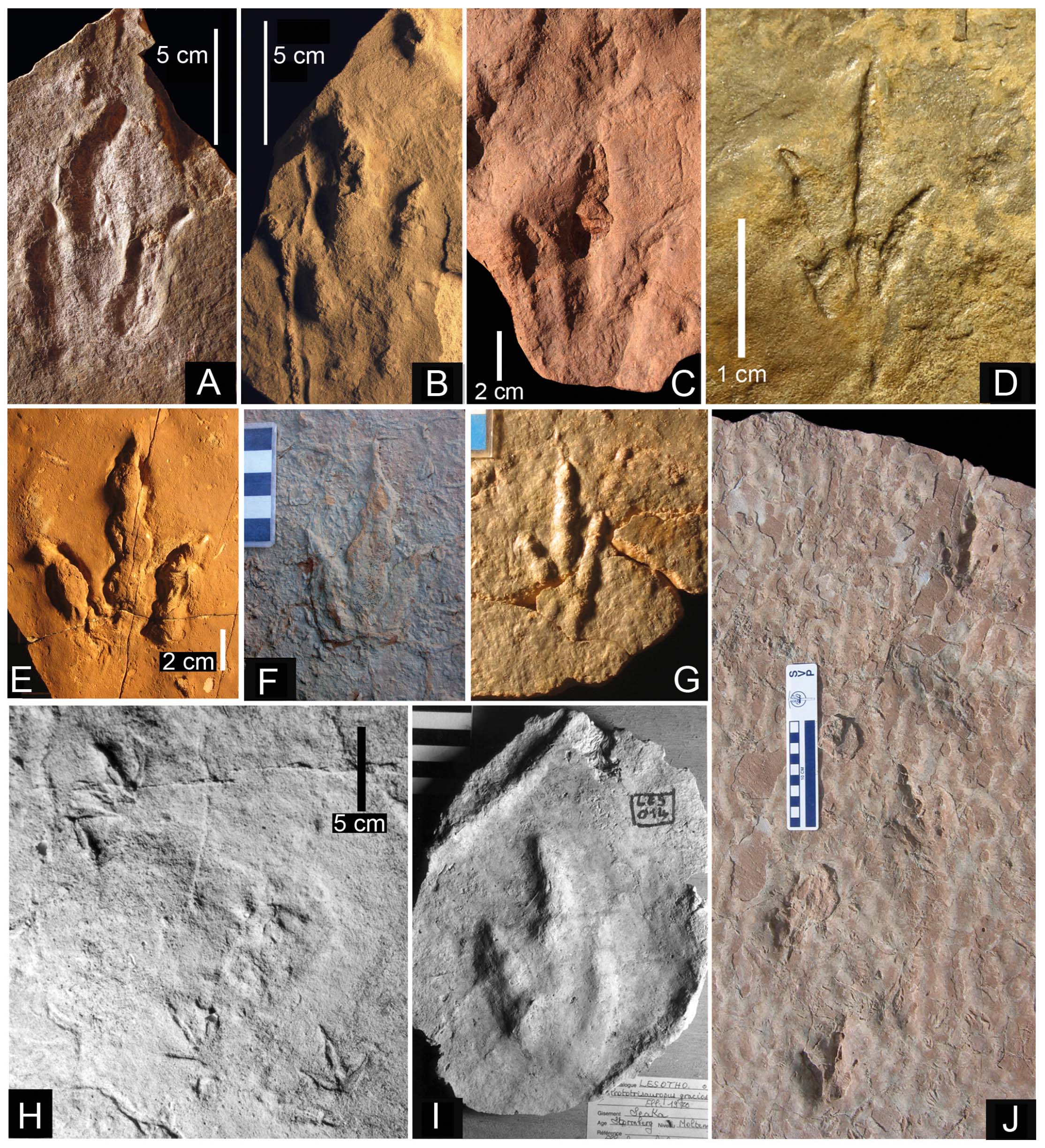

The ichnogenus Rotodactylus was introduced by Peabody (1948) based on material from the Lower-Middle Triassic Moenkopi Formation of Arizona and Utah, USA (Fig.1A). Characteristic features of Rotodactylus are: 1) pes with compact and dominant digit group II-IV with a narrow proximal connection; digits mostly parallel or slightly diverging, increasing in length from I-IV and digit IV longest; digit I very short and often isolated; digit V with a small circular impression far posterior and in line with digit IV; manus similar in morphology but smaller, in some ichnospecies with digit IV < digit III; 2) primary lateral overstep of the manus by the pes, variable; and 3) long strides recorded from fast moving individuals (Fig. 1AC). Rotodactylus footprints are known from Lower to Middle Triassic deposits in North America (Arizona, Utah), Europe (Germany, France, Italy, Poland), and North Africa (Morocco, Algeria) (Peabody, 1948; Demathieu, 1970; Haubold, 1971a, b; Gand, 1974a; Avanzini & Mietto, 2008; Klein & Lucas, 2010b, 2018, 2021; Klein et al., 2011; Fichter & Kunz, 2013; Niedźwiedzki et al., 2013). Especially in the German Buntsandstein (Middle Triassic, Anisian) and in the French Middle Triassic along the Massif Central it occurs in mass accumulations on surfaces with chirotheriids (Fig. 1B). Rotodactylus has convincingly been attributed to Dinosauromorpha by Haubold (1999), who considered the trackmaker to be small agile forms similar to Lagerpeton whose skeletons are known from Middle-?Late Triassic deposits of Argentina (Sereno & Arcucci, 1993; Nesbitt, 2011; Müller et al., 2018). Recently Lagerpeton has been reanalysed and its phylogenetic position found to be closer to pterosaurs than to dinosaurs (García & Müller, 2025). According to these authors Lagerpeton and other lagerpetids belong to basal Pterosauromorpha and the pterosaur stem instead to Dinosauromorpha. Whatever the exact phylogenetic position of Lagerpeton is, pes and skeletal proportions and the suggested gait perfectly match with Rotodactylus tracks and trackways.

- Rotodactylus (dinosauromorph) footprints and trackways from Middle Triassic deposits. A. Rotodactylus cursorius (R. “mckeei”) from upper red formation (Moenkopi Group, Middle Triassic, Anisian) of Utah (from Klein and Lucas, 2010b). B. R. matthesi with Chirotherium sickleri (red colour) from Solling Formation (Buntsandstein, Middle Triassic, Anisian) of Thuringia, Germany. C. Interpretive sketches of R. cursorius (top left and centre left) and R. matthesi (bottom left and right) (from Peabody, 1948; Haubold, 1971b).

Brusatte et al. (2011) and Niedźwiedzki et al. (2013) proposed Prorotodactylus, an ichnotaxon originally described from the Wióry Formation (Lower Triassic, Olenekian) of Poland to represent a precursor of the Middle Triassic Rotodactylus indicating an earlier origin of the dinosaur stem. However, Klein & Lucas (2021) questioned this conclusion. Prorotodactylus slightly resembles the archosauromorph/lepidosauromorph track Rhynchosauroides. However in Prorotodactylus manual digit IV is shorter than digit III whereas in Rhynchosauroides it is longer or subequal with III (see also discussion on this in Klein & Niedźwiedzki, 2012). The interpretation of Prorotodactylus is still debated and needs further study.

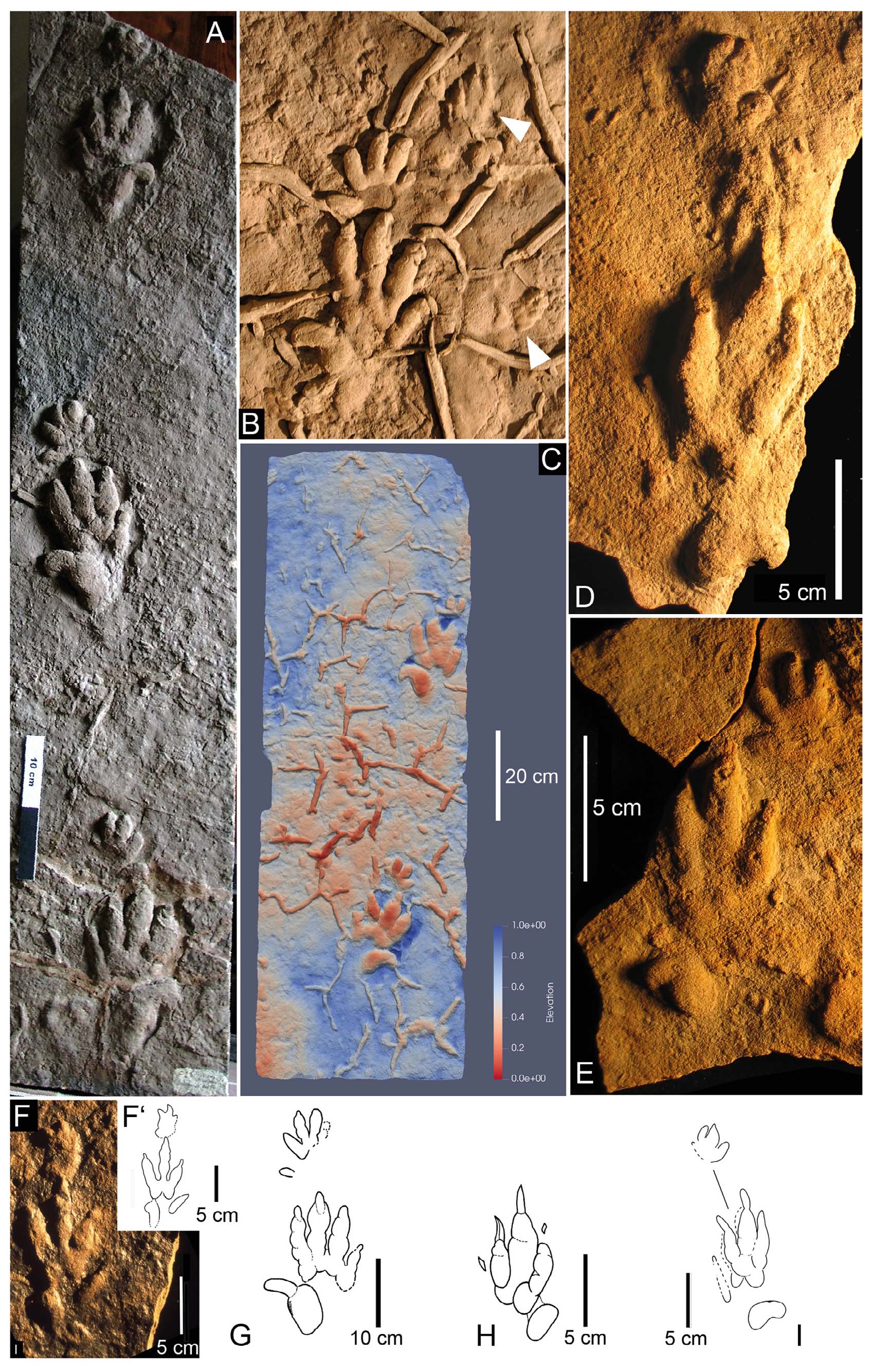

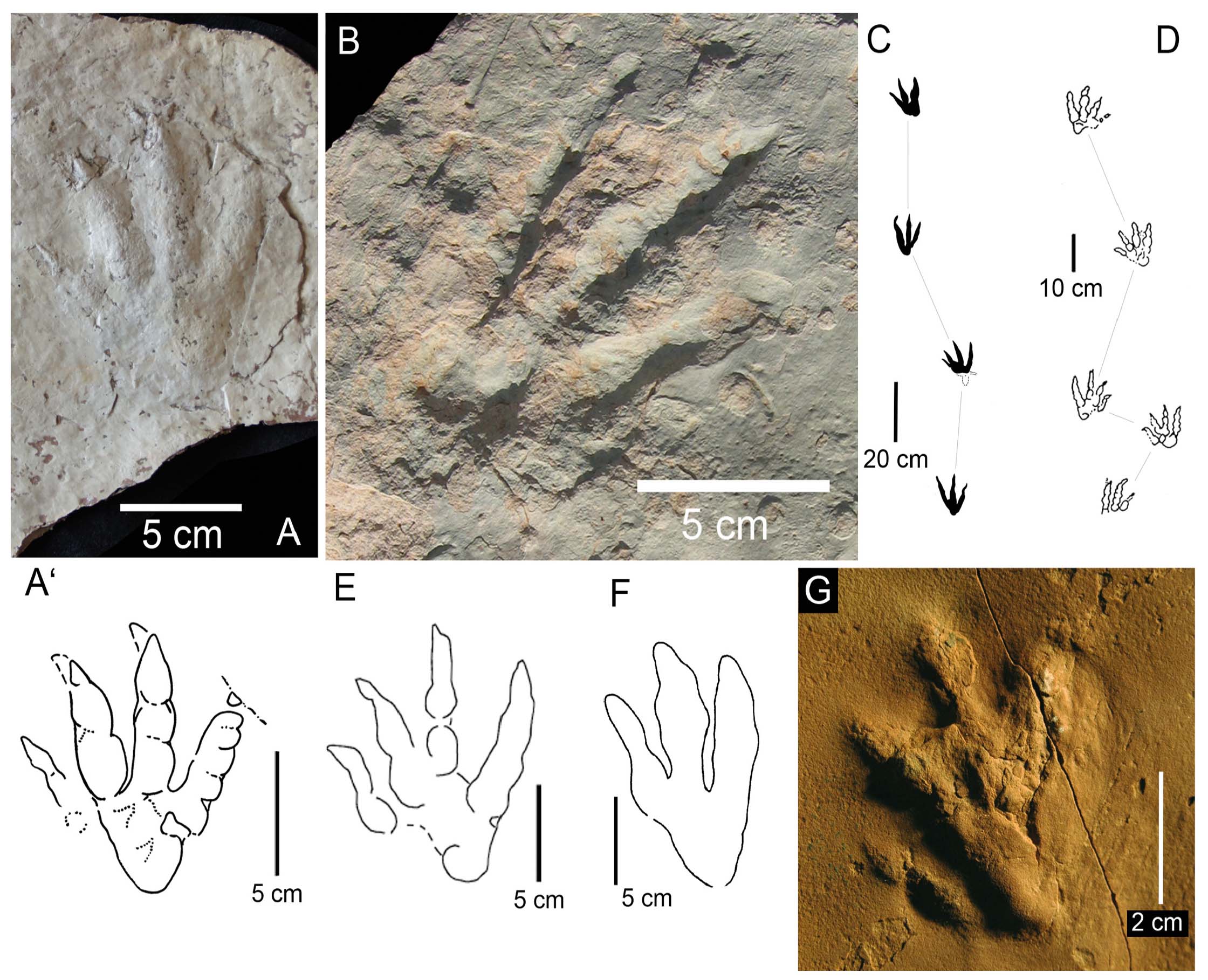

Chirotherium and the evolution of the functionally tridactyl pes

The first tendencies towards a mesaxonic, functionally tridactyl (“dinosaurian”) pes composed of digits II, III, IV with reduced and short digits I and V in the evolution of archosaurs can be seen in chirotheriids, more precisely in the ichnogenus Chirotherium. Chirotherium barthii, which was originally described from the Buntsandstein (Middle Triassic, Anisian) of the famous Hildburghausen locality in southern Thuringia, Germany (Kaup, 1835a, b), is recorded from Middle Triassic (Anisian) deposits in a Pangaea-wide distribution (see above) and has a dominant digit group II-IV with digit III longest and II and IV shorter and subequal in length (Fig. 2A-C, G). Digit I is shortest and slightly posteriorly shifted. Digit V consists of a large oval basal pad and a thinner backward curved phalangeal part. The round metatarsophalangeal pads I-IV commonly show a half circular arrangement and concave arch, respectively. Well developed pads are impressed in well preserved specimens. The manus is much smaller, has a more round shape with digit III longest and I shortest. Characteristically, manual digit IV is much reduced, shorter than II and slightly laterally spread, a feature that has been listed by some authors as a dinosaurian character (see Haubold & Klein, 2000, 2002; Olsen & Baird, 1986). Other footprints that formerly were described as nonchirotheriid --Sphingopus ferox, S. ladinicus and Parachirotherium postchirotherioides (Demathieu, 1966; Avanzini & Wachter, 2012; Rehnelt, 1950; Kuhn, 1958a) -- recently were synonymised with Chirotherium under the new combinations C. ferox, C. ladinicum and C. postchirotherioides (Klein & Lucas, 2021; Fig. D-F, F’, H, I) and have been interpreted to represent a continuation of an evolutionary trend towards the functionally tridactyl (“dinosaurian”) pes (Haubold & Klein 2000, 2002). Chirotherium (“Sphingopus”) ferox was originally introduced based on material from the Middle Triassic (Anisian-Ladinian) of the Massif Central, France (Demathieu, 1966, 1970) and subsequently documented from numerous trackways and footprints along large surfaces in this region (e.g. Gand, 1974a). Outside of France S. ferox was described from the Middle Triassic siliciclastic marginal Muschelkalk (Anisian) of Bavaria (Germany) along the Bohemian Massif (Klein & Lucas, 2018). A second ichnospecies, C. ladinicum, was introduced by Avanzini & Wachtler (2012) based on footprints from the Middle Triassic of the Dolomites, northern Italy. Characteristic is the functionally tridactyl pes, which is much more slender if compared with Chirotherium barthii (Fig. 2 D-E, H-I). Digit I shows a more extensive posterior shift and often is impressed only by the distal trace of the claw. Also, digit V is much more reduced relative to the condition in C. barthii. Chirotherium (“Parachirotherium”) postchirotherioides (Fig. 2F, F’) is similar in overall shape to C. ferox, but less slender. It comes from the Benk Formation (Middle Keuper, Middle Triassic, late Ladinian) of Bavaria, Germany (Rehnelt, 1950; Kuhn, 1958a; Haubold & Klein, 2000, 2002) and has been proposed to be part of a plexus Parachirotherium-Atreipus-Grallator representing the footprints of facultative bipedal archosaurs, possibly dinosauriforms (Haubold & Klein, 2000, 2002; Sereno & Arcucci, 1994). Chirotherium and the evolution of a functionally tridactyl pes could potentially have originated in some basal Avemetatarsalia, even if the aphanosaurian Teleocrater from the Middle Triassic of East Africa (Nesbitt, 2017a, b) still kept the crocodile-line ankle and a more plantigrade foot posture. The fossil record of these basal forms is scarce and still incomplete. Future discoveries might show a larger diversity. On the other hand, a functionally tridactyl pes combined with bipedal gait has independently evolved also in crocodile-line archosaurs such as Poposaurus (Farlow et al., 2014) and pseudosuchian affinities of some of these tracks therefore cannot be excluded. Because of the reassignment to Chirotherium (Klein & Lucas, 2021) this plexus should be modified here as Chirotherium-Atreipus-Grallator. Footprints similar to Chirotherium (“Parachirotherium”) postchirotherioides have also been found in stratigraphically younger deposits of Morocco (Lagnaoui, 2012, 2016; Zouheir et al., 2018).

- Chirotherium footprints and trackways from the Middle Triassic. A-C. C. barthii from type surface in the Solling Formation (Thüringischer Chirotheriensandstein, Middle Triassic, Anisian) of Hildburghausen, Germany as photographs (A-B) and false colour depth model (C). D-E. Chirotherium (“Sphingopus”) ferox from Eschenbach Formation (Muschelkalk, Middle Triassic, Anisian) of Germany. F, F’ Chirotherium (“Parachirotherium” postchirotherioides) from Benk Formation (Middle Triassic, Ladinian) of Germany as photograph and interpretive sketch. G-I. Interpretive sketches of Chirotherium from Middle Triassic deposits. G. C. barthii from Germany, H. C. ferox (holotype of Sphingopus ferox) from France. I. C. ferox from Germany. A-B. Courtesy H. Haubold. C. Courtesy Jens N. Lallensack. D-I. From Klein & Lucas, 2018, 2021).

Atreipus-Grallator-Eubrontes and the evolution of the bipedal gait (Fig. 3-7)

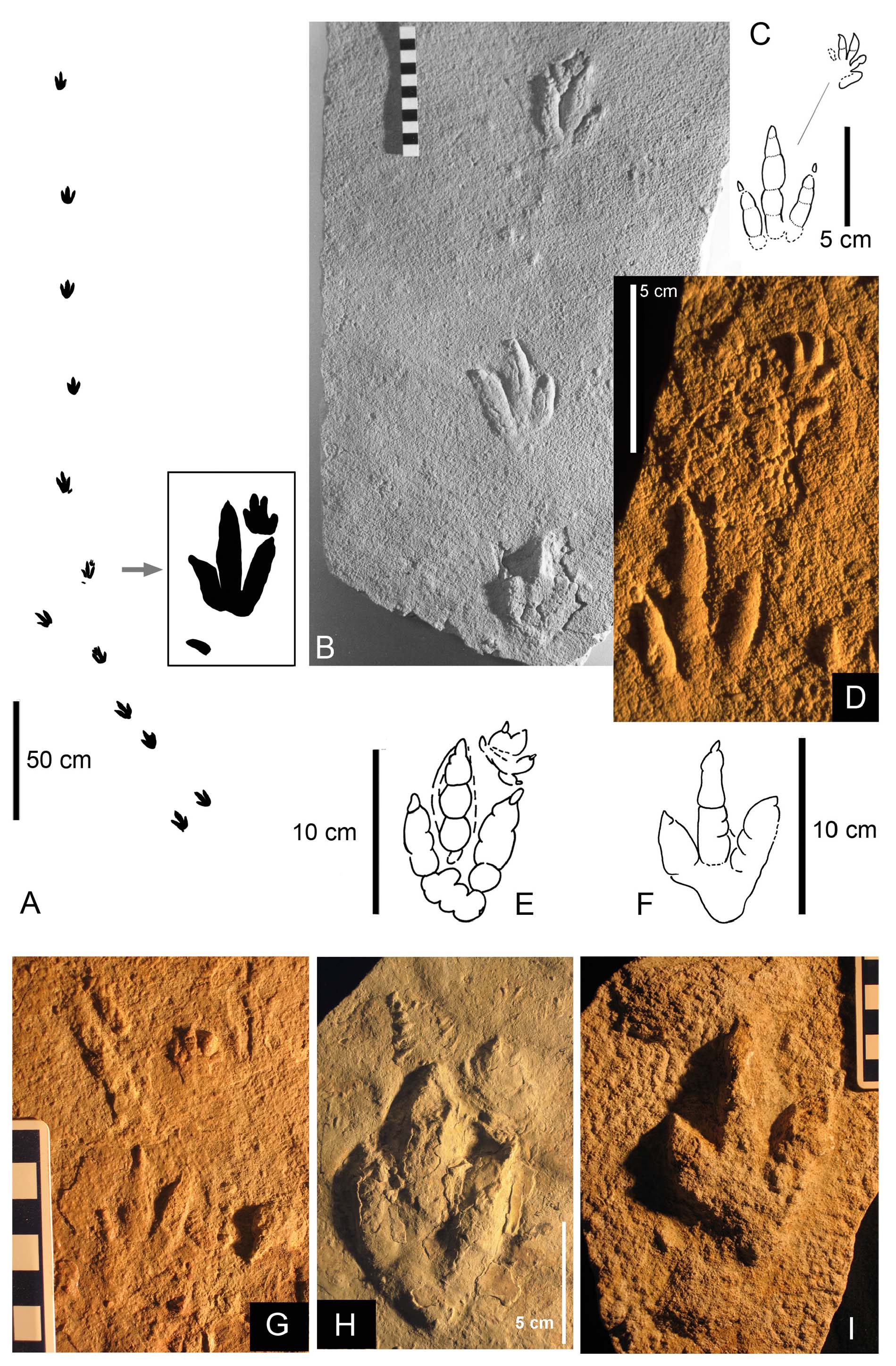

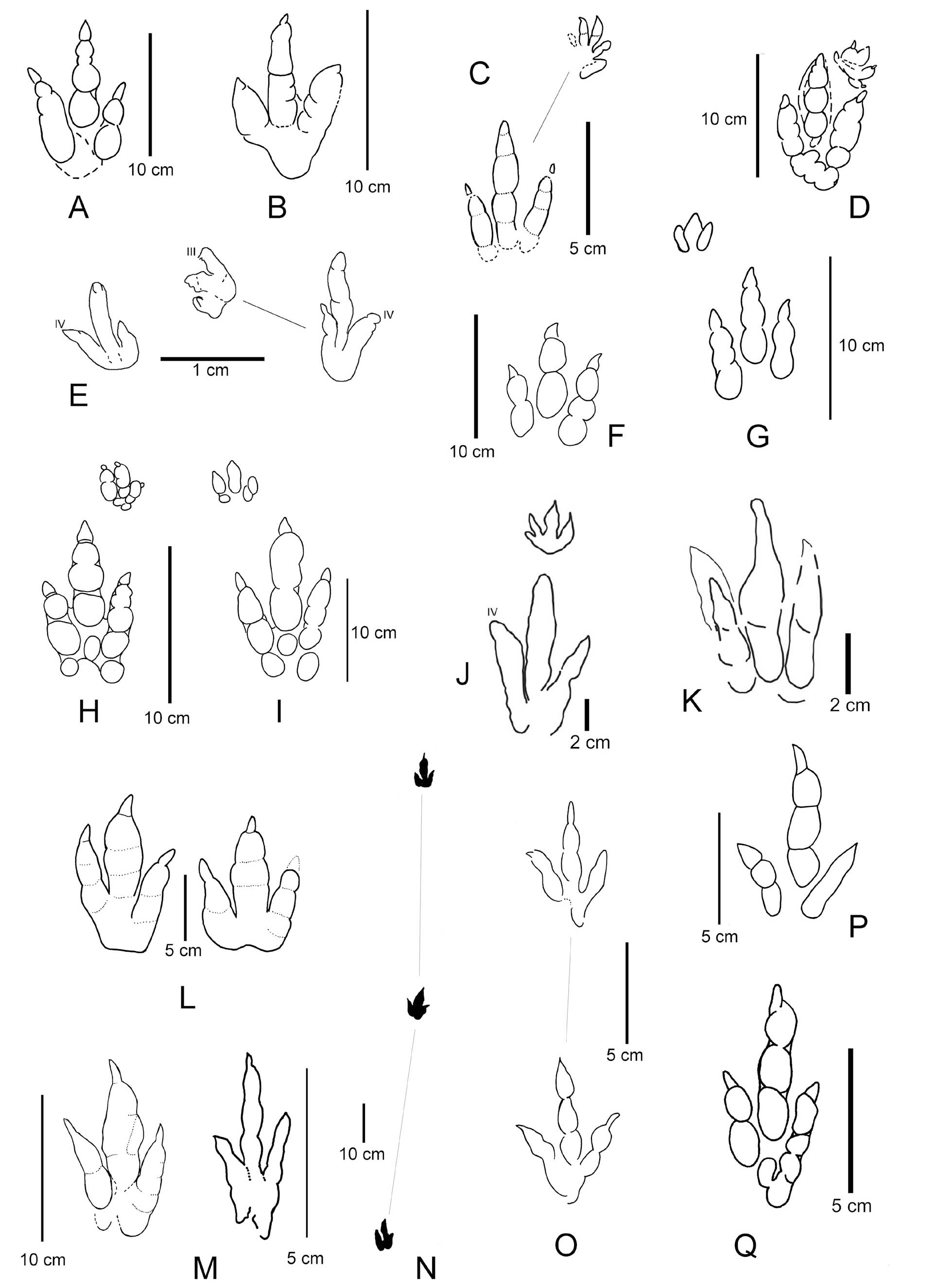

- Functionally tridactyl mesaxonic footprints from the Middle Triassic, possibly left by facultative bipeds, as photographs and interpretive sketches. A-D. Atreipus-Grallator (“Coelurosaurichnus”) from Benk Formation (Middle Triassic, Ladinian) of Germany. E-I. Atreipus-Grallator (“Coelurosaurichnus”) From the Middle Triassic of France. All from Klein & Lucas (2021).

- Mesaxonic tridactyl footprints from the Late Triassic. A-B. Atreipus from Hassberge Formation (Coburger Sandstein, Carnian) of Germany. C. Atreipus from Bigoudine Formation (T6, ?Norian) of the Argana Basin, Morocco. D. Banisterobates from Dry Fork Formation (Carnian) of Virginia, USA. E-F. Grallator from Redonda Formation, Chinle Group (Norian-Rhaetian), New Mexico, USA. G. Small (?juvenile) Grallator from Hassberge Formation (Coburger Sandstein, Carnian) of Germany. H-I. Bird-like footprints Trisauropodiscus and Grallator from Lower Elliot Formation (Norian) of Lesotho, southern Africa. J. Grallator from Redonda Formation (Norian-Rhaetian) of New Mexico, USA. From Klein & Lucas (2021).

- Different Atreipus-Grallator plexus tridactyl footprints from the Middle-Upper Triassic. A-B, From Middle Triassic (Anisian-Ladinian) of France. C, From Benk Fm. (Ladinian) of Germany. D, From Middle Triassic (Anisian-Ladinian) of France. E, From Timezgadiouine Fm. (T4, Anisian) of the Argana Basin, Morocco. F-G, From Late Triassic (Carnian) of France. H, From Late Triassic of Newark Supergroup, North America. I, From Steigerwald Fm. (Carnian) of Germany. J-K, From Bigoudine and Timezgadiouine formations (T6, T5, Carnian-Norian) of the Argana Basin, Morocco. L, From Hassberge Fm. (Carnian) of Germany. M, From Hassberge Fm. (Carnian) of Germany. N, From Redonda Fm. (Chinle Group, Norian-Rhaetian) of New Mexico. O-P, From Chinle Group, North America. Q, Grallator cursorius composite drawing from type trackway, Early Jurassic of Newark Supergroup, North America. Sketches from Courel & Demathieu (2000), Haubold & Klein (2000, 2002), Gand et al. (2005), Klein & Lucas (2010a), Klein et al. (2011) and Lagnaoui et al. (2012).

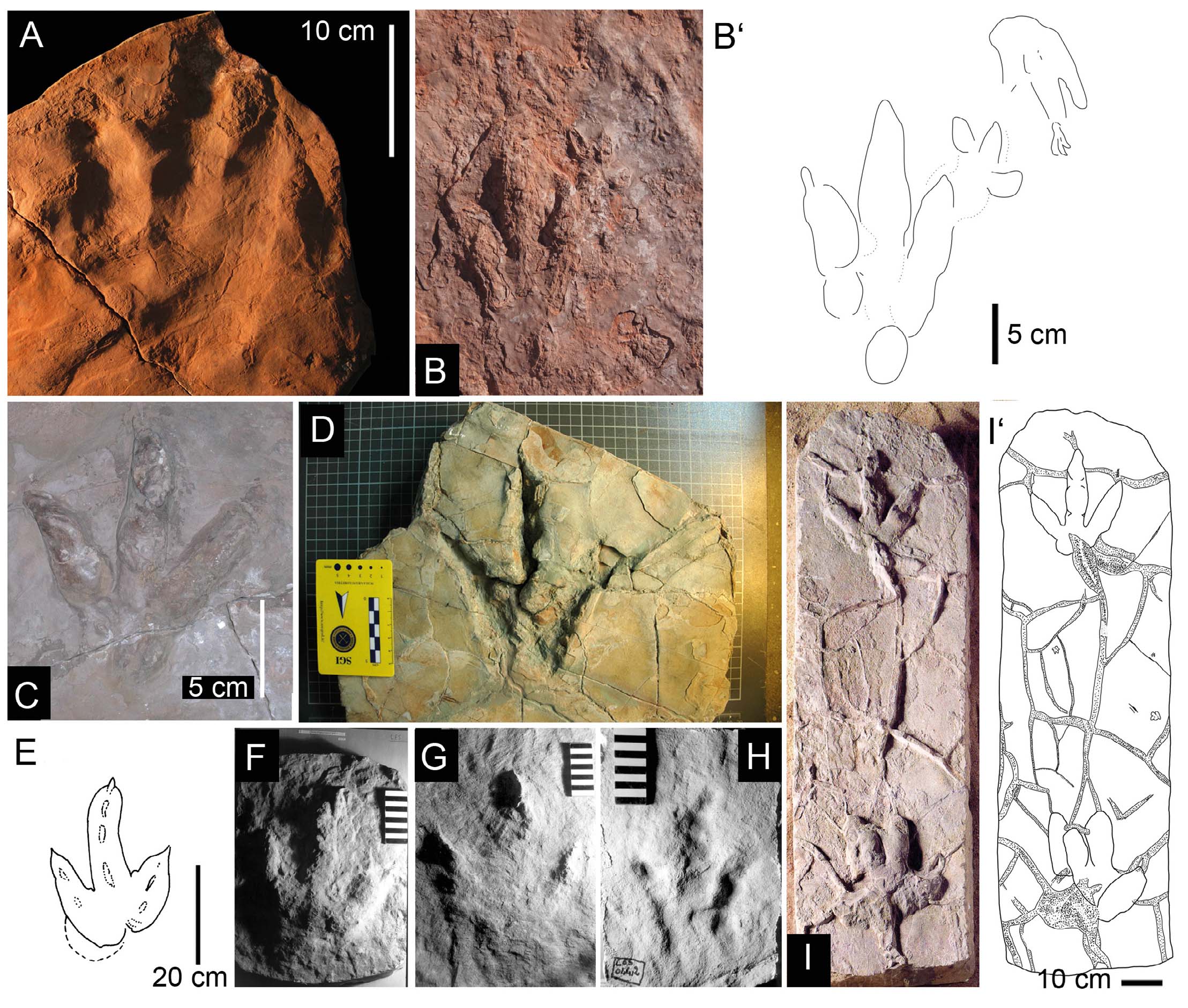

- Large Eubrontes-size tridactyl footprints from the Late Triassic as photographs and interpretive sketches. A-B, B‘. Eubrontes isp. and Atreipus-Grallator-Eubrontes plexus form from Timezgadiouine Formation (T5, Carnian) of the Argana Basin, Morocco (B-B‘ with associated manus imprint). C-D. Grallator-Anchisauripus-Eubrontes plexus footprint from Ørsted Dal Formation of Fleming Fjord Group, Eastern Greenland. E-H. Grallator-Anchisauripus-Eubrontes plexus footprints from Lower Elliot Formation (Norian) of Lesotho, southern Africa as interpretive sketch and photographs. I-I‘ Pengxianpus xifengensis (Holotype) from Xujiahe Formation (Norian-Rhaetian) of Sichuan Province, China. From Lagnaoui et al. (2012), Zouheir et al. (2020), Klein & Lucas (2021), Ellenberger (1972), Xing et al. (2013), Klein & Lucas (2021).

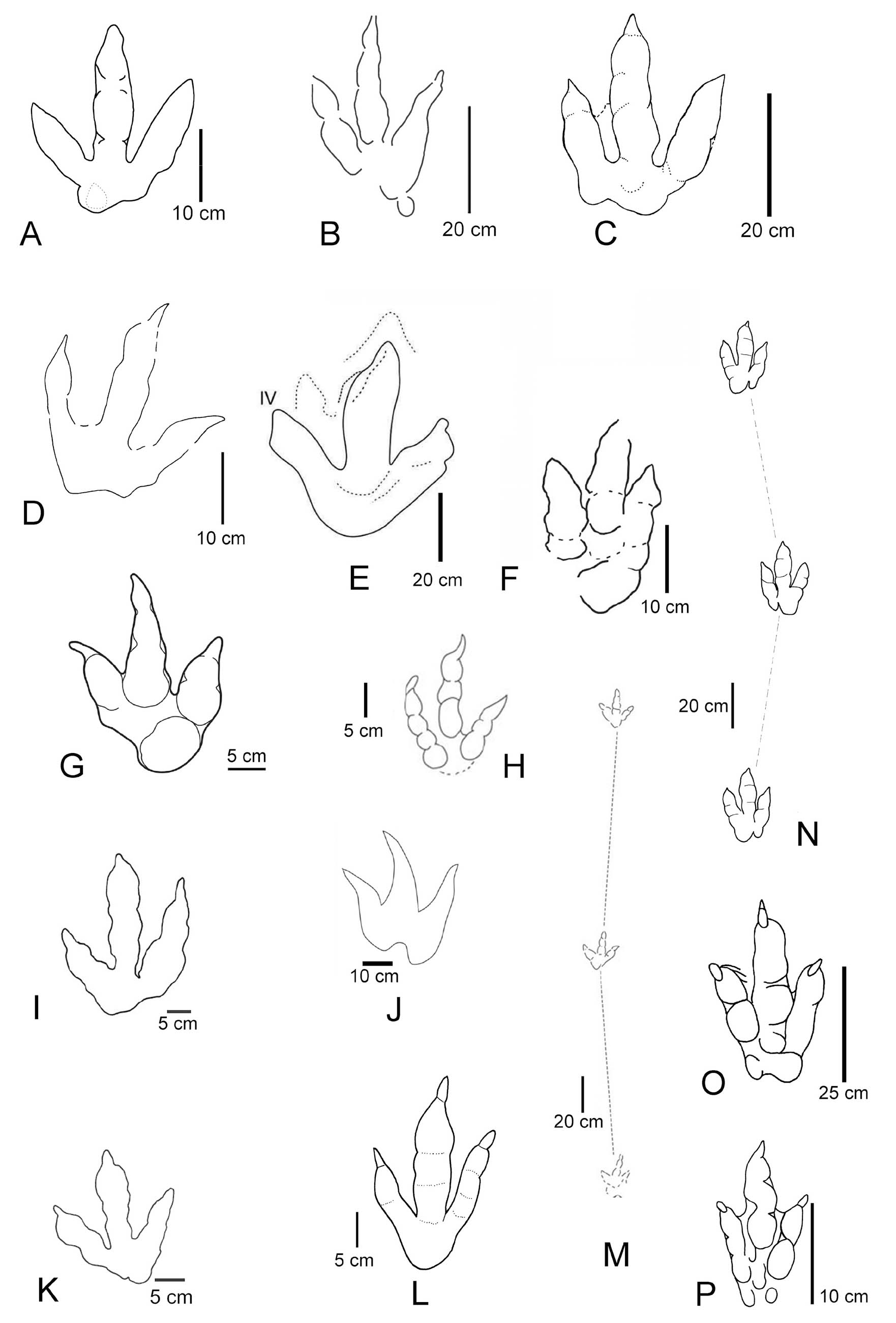

- Large theropod footprints from the Triassic as sketches. A, Pengxianpus cifengensis from Xujiahe Fm. (Late Triassic) of Sichuan Province, China. B-O. Anchisauripus-Eubrontes. B, From Lower Elliot Fm. (Norian) of Lesotho, Southern Africa. C, From Höganäs Fm. (Late Triassic, Rhaetian) of southern Sweden. D, From Lower Elliot Fm. (Norian) of Lesotho, Southern Africa. E-F, From Timezgadiouine Fm. (T5, Carnian) of the Argana Basin, Morocco. G, From Late Triassic (Carnian) of the Southern Alps. H, From Late Triassic (Norian) of southern France. I, From Tomanová Fm. (?Late Norian-Rhaetian) of Slovakia. J, From Caturrita Fm. (Early Jurassic of Brazil. K, From Tomanová Fm. (?Late Norian Rhaetian) of Slovakia. L, From Early Jurassic (Hettangian) of northern Bavaria, Germany. M, From Late Triassic (Norian) of southern France. N-O, Eubrontes giganteus from Early Jurassic of Newark Supergroup, North America (O = type). P, Anchisauripus sillimani (type) from Early Jurassic of Newark Supergroup, North America. Sketches from Ellenberger et al. (1970), Haubold (1971b, 1984), Gierliński & Ahlberg (1994), Olsen et al. (1998), Gand et al. (2000), Lucas et al. (2006), Klein & Haubold (2007), Niedźwiedzki (2011), Lagnaoui et al. (2012), Silva et al. (2012), Bernardi et al. (2013) and Xing et al. (2013).

The ichnogenus Atreipus was established by Olsen & Baird (1986). The type material comes from the Late Triassic of the Newark Supergroup in eastern North America. It is characterised by a five-toed grallatorid pes imprint combined with a small tridactyl-pentadactyl manus impression. A diagnostic feature also is the distinct impression of both metatarsophalangeal pads II and III. A problem of ichnotaxonomy and identification of Atreipus has been discussed by Haubold & Klein (2000, 2002). According to these authors the presence/absence of a manus as well as the completeness of metatarsophalangeal pads in the pes imprints can depend on 1) preservational factors, and 2) variation of the gait of a facultative biped they considered as the probable trackmaker. Therefore Atreipus (footprints with a manus imprint) and Grallator (footprints lacking a manus imprint) may sometimes represent the same trackmaker. This has been observed along trackways from the Middle Triassic (Ladinian) Benk Formation of Germany (Haubold & Klein, 2000, 2002; Fig. 3A-D). Trackways of facultative bipeds could for example represent silesaurids that were widespread in Middle-Late Triassic deposits of Europe, North America, South America, North Africa and East Africa (Dzik, 2003; Nesbitt et al., 2010, 2011, 2013). From Middle Triassic (Anisian-Ladinian) deposits of the Massif Central in France similar footprints have been described and assigned to the different ichnogenera Coelurosaurichnus and Anchisauripus (Demathieu, 1970, 1989; Demathieu & Gand, 1972, 1981a; Demathieu & Demathieu, 2004; Gand, 1974a, b, 1976, 1979; Gand & Demathieu, 2005; Gand et al., 1976; Courel & Demathieu, 1976) (Fig. 3E-I). Coelurosaurichnus was introduced by v. Huene (1941) based on material from the Middle Triassic (Ladinian) Quarziti del Monte Serra Formation of the Monti Pisani, Tuscany, Italy (see also Marchetti et al., 2021). Leonardi & Lockley (1995) proposed to abandon the name because they considered it to be a junior synonym of Grallator. Nevertheless, it is still in use by French ichnologists who also assigned material from the Late Triassic of France to Coelurosaurichnus (Courel & Demathieu, 2000; Gand et al., 2000, 2005). Marchetti et al. (2021) referred the holotype of Coelurosaurichnus to Atreipus, although a manus imprint cannot be observed, possibly due to the incompleteness of the specimen. Haubold & Klein (2000, 2002) considered Coelurosaurichnus to belong to the Atreipus-Grallator plexus.

Banisterobates (type ichnospecies B. boisseaui; Fig. 4D) is a very small (pes length 1.8-2.5 cm), functionally tridactyltetradactyl footprint described from the Dry Fork Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) of Virgina, USA by Fraser & Olsen (1996). The trackway shows three successive sets preserved. It resembles Atreipus and could represent a juvenile. Nevertheless, Atreipus has no hallux impression, as it is observed in Banisterobates.

Trisauropodiscus are small tridactyl, non-grallatorid footprints of a biped that have originally been described from the Lower-Upper Elliot formations (Late Triassic-Early Jurassic) of Lesotho, southern Africa (Ellenberger, 1970, 1972; see also Abrahams & Bordy, 2023; Fig. 4H). They show a bird-like shape with wide digit divarication. Theropods with a bird-like pes as well as ornithischian dinosaurs have been discussed as the producers. The ornithischian interpretation is based on similarities of these footprints with the ornithischian track Anomoepus. See discussion in Gierliński et al. (2017).

In the footsteps of early sauropodomorphs

Pseudotetrasauropus (Fig. 8A-B, E-H) is an ichnogenus introduced by Ellenberger (1972) for material from the Lower Elliot Formation (Late Triassic, Norian-Rhaetian) of Lesotho, southern Africa. Further possible occurrences are, for example, in the Late Triassic of southwestern France (Ellenberger, 1965; Ellenberger et al., 1970; Gand et al., 2000; Rainforth, 2003; D’Orazi-Porchetti, 2007) and in the Hauptdolomit-Kössen formations of Switzerland (Meyer et al., 2022). Purported North American occurrences in the Chinle Group were later reassigned to Evazoum (Lockley, 2006b; Lucas et al., 2010; Klein & Lucas, 2021; see also below). The type ichnospecies P. bipedoida and other ichnospecies were partly described with long trackways preserved as concave epireliefs left in situ. Paul Ellenberger, however, produced numerous plaster casts that are deposited in the collection of the University of Montpellier, France. The trackways were left by bipeds and therefore only show digitigrade pes imprints preserved that are tetradactyl-pentadactyl. Digit III is longest, followed by digit II, IV and I, which is shortest. Digit V is impressed with an oval basal pad posterior to the digit group I-IV and in line with digit IV. All digits have round distal ends, mostly lacking distinct claw traces. Trackways have short steps and with footprints rotated inward or outward. Pseudotetrasauropus shows some morphological similarities with Brachychirotherium in the oval digit V impression, in the rounded, broad distal ends of digits and in the digit proportions with IV < II. It has been considered synonymous with these chirotheres (“bipedal Brachychirotherium”) by Olsen & Galton (1984), however, no bipedal version of typical Brachychirotherium is known from classical localities in Europe and North America. Pseudotetrasauropus is generally accepted as the trackway of a bipedal sauropodomorph.

- Triassic sauropodomorph footprints. A-B. Pseudotetrasauropus bipedoida (Holotype) from Lower Elliot Formation of Lesotho, southern Africa as interpretive sketch and photograph of plaster cast. C-D. Tetrasauropus unguiferus (Holotype) as interpretive sketch and photograph from same unit and locality as A-B. E-H. Pseudotetrasauropus from Hauptdolomit Formation (Norian) of Graubünden, Swiss Alps as photographs and false colour depth and contour line models. I-K. Eosauropus cimarronensis from Sloan Canyon Formation (Chinle Group, Late Triassic) of New Mexico USA. L-N. Eosauropus isp. from Ørsted Dal Formation of Fleming Fjord Group in Eastern Greenland as false colour depth models and automated outline sketch. From D’Orazi Porchetti & Nicosia, 2007; Meyer et al. (2022); Lockley et al. (2006); Klein & Lucas, 2021; Lallensack et al. (2017).

Tetrasauropus (Fig. 8 C-D) was originally described by Ellenberger (1970, 1972) from the Lower Elliot Formation (Late Triassic (Norian-Rhaetian) of Lesotho, southern Africa (see also D’Orazi-Porchetti and Nicosia, 2007). Pes and manus imprints are tetradactyl, broad, and plantigrade with a wide, rounded “heel.” Digits are short with sharp claw traces that are strongly bent inward. Trackways are broad, with short steps and manus imprints placed anterolaterally to the pes imprints. Both pes and manus imprints are oriented parallel to the trackway midline. Tetrasauropus was reported also from numerous other localities in Europe (Lockley & Meyer, 2000), North America (Lockley & Hunt, 1995; Lockley et al., 2001) and Greenland (Lockley & Meyer, 2000). Some of these materials were later reassigned to other ichnogenera. Besides specimens from southern Africa, including the type material, we tentatively assign an isolated footprint from the Hauptdolomit-Kössen formations (Late Triassic, Norian-Rhaetian) to represent Tetrasauropus, following Meyer et al. (2022). The ichnogenus is generally considered to be the trackway of a quadrupedal sauropodomorph.

Eosauropus (Fig. 8I-N) was introduced by Lockley et al. (2006a) based on footprints of a large quadruped from the Chinle Group of USA. It shows strong heteropody, plantigrade elongate oval pes imprints with four to five strongly outward directed short digit traces. The manus imprint is much smaller, short and broad, tetradactyl-pentadactyl, with outward pointing digit traces and with a concave margin posteriorly. Trackways display a narrow gauge and short steps. Eosauropus has a wide geographical distribution in the Norian-Rhaetian of the western USA (Lucas et al., 2010; Lockley et al., 2001, 2011, 2006a), Greenland (Jenkins et al., 1994; Niedźwiedzki et al., 2014; Lallensack et al., 2017), Europe [Great Britain (Lockley et al., 1996, 2006; Lockley & Meyer, 2000), Italy (Nicosia & Loi, 2003)], and possibly China (Xing et al., 2018). Eosauropus is considered to be the track of a sauropodomorph (Wright, 2005; Wilson, 2005; Lockley et al., 2006a). Lallensack et al. (2017) attribute Eosauropus to sauropodiforms, probably eusauropods, based on the semi-digitigrade pes with laterally deflected unguals.

Evazoum (Fig. 9) was originally described from the Montemarcello Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) of La Spezia, Italy (Nicosia & Loi, 2003). It is characterised by a tridactyltetradactyl pes imprint of a biped with digit III being only slightly longer than II and IV, whereas digit I (hallux) is short and distally curved inward. Claw traces are triangular and sharp. Posteriorly the footprints end in a pronounced “heel” or metatarsophalangeal pad. Trackways show wide pace angulation (140°-170°) and slight inward rotation of footprints. Other occurrences in Europe are in the Travenanzes Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) of the Dolomites (Northern Italy) (D’Orazi-Porchetti et al., 2008), and the Hassberge Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) of Germany (Haderer, 2015). The Chinle Group (Norian-Rhaetian) of the western USA yielded abundant footprints first described under Pseudotetrasauropus (e.g., Lockley & Hunt, 1993; Lockley et al., 2000; see Lucas et al., 2010; Klein & Lucas, 2021 for overview) and later referred to Evazoum (Lockley, 2006b; Lucas et al., 2010; Lockley & Lucas, 2013). Klein et al., 2006 considered some Evazoum from the Redonda Formation (Chinle Group) as extramorphological variants of Brachychirotherium. Eastern Greenland yielded a trackway from the Ørsted Dal Formation of the Fleming Fjord Group that has been assigned to Evazoum isp. (Lallensack et al., 2017). Evazoum is generally accepted as a sauropodomorph dinosaur track (Farlow et al., 2022), even if other attributions, e.g. to pseudosuchian archosaurs, have been proposed as well (D’Orazi-Porchetti et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2023). Recently a possible occurrence from the Blackstone Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) of Queensland, Australia has been reported (Romilio et al., 2022).

-Triassic sauropodomorph footprints Evazoum. A, A’. E. sirigui plaster cast of holotype from Montemarcello Formation (Carnian) of Italy in the collection of the Earth Science Department, University of Rome. B-F. E. sirigui from Redonda Formation (Chinle Group, Norian-Rhaetian) of New Mexico, USA. G. Possible small (?juvenile) Evazoum from Timezgadiouine Formation (T5) of the Argana Basin, Morocco. From Lucas et al. (2010), Klein & Lucas (2021), Lagnaoui et al. (2012).

STRATIGRAPHIC UNITS AND LOCALITIES WITH TRIASSIC DINOSAUROMORPH-DINOSAUR FOOTPRINTS

Africa

Algeria

Rotodactylus dinosauromorph footprints have been documented from the Haizer-Akouker unit (Middle Triassic) of the Djurdjura Mountains, Algeria. (Kotanski et al., 2004).

Tunisia

Footprints from Middle-Late Triassic Ouled Chebbi, Kirchaou and Azizia formations of Tunisia were described by Niedźwiedzki et al. (2017). They were attributed by these authors to Dinosauromorpha and Therapsida. The tridactyls can be assigned to the Atreipus-Grallator-Eubrontes plexus.

Morocco

In recent years Morocco became a hotspot for research in Paleozoic-Mesozoic vertebrate ichnology. Diverse Triassic ichnoassemblages have been documented, in particular from the Argana, Ourika and Yagour basins of the Western High Atlas region and from the Sidi Saïd Maachou Basin in the Western Meseta. Most abundant are chirothere footprints (Protochirotherium, Synaptichnium, Chirotherium, Brachychirotherium) from the Early-Late Triassic Timezgadiouine and Bigoudine formations (Olenekian-Anisian, Carnian-Norian, T3-T6) (Klein et al., 2010, 2011; Lagnaoui et al., 2012, 2016; Zouheir et al., 2020), but also from the Oukaimeden Sandstone Formation (Ladinian-Carnian) of the Ourika Basin, and from the Oued Oum Er Rbiaa Formation (Norian) of the Moroccan Western Meseta (Biron & Dutuit, 1981; Hminna et al., 2013, 2021; Moreau et al., 2024). Associated tetrapod ichnotaxa consist of Atreipus-Grallator, Apatopus, Rotodactylus, Rhynchosauroides and Procolophonichnium. Most dinosaur footprints come from the Timezgadiouine Formation (T5-T6, Carnian-Norian). These are small to large-sized tridactyl footprints belonging to the Atreipus-Grallator and Grallator-Eubrontes plexus.

Lesotho, South Africa

Lesotho and RSA in southern Africa yielded rich tetrapod footprint assemblages dominated by tridactyl Grallator-Eubrontes (theropods) and occasional Trisauropodiscus (birdlike theropods; Abrahams & Bordy, 2023) and tetradactyl-pentadactyl Tetrasauropus and Pseudotetrasauropus (sauropodomorphs). These come from the Molteno and Lower Elliot formations. The ichnofaunas have been extensively documented and described by Paul Ellenberger and others (Ellenberger, 1970, 1972; Ellenberger et al., 1970; see also Raath et al., 1990). Paul Ellenberger introduced many new dinosaur ichnotaxa and names, most of which are considered synonyms of Grallator and Eubrontes. Tetrasauropus and Pseudotetrasauropus are considered as valid ichnogenera, even if a few specimens originally assigned to these were reidentified as chirotheriids. More recently some ichnoassemblages have been restudied by Bordy et al. (2017) and Abrahams et al. (2022, 2023).

Asia

China

From China Triassic dinosaur footprints are known from the Xujiahe Formation (Norian-Rhaetian) of Sichuan Province. Yang & Yang (1987) introduced the new ichnogenus Pengxianpus for Eubrontes-like (pl > 25 cm) tridactyl pes imprints that can be attributed to a theropod (see revision by Xing et al., 2013). Small tridactyl dinosaur tracks (pes length 11 cm) also come from this unit. Furthermore, sauropodomorph tracks similar to Eosauropus were documented from the Xujiahe Formation (Late Triassic) of Sichuan Province (Xing et al., 2018), however, they are different in the inward rotation of the footprints, whereas they are outwardly rotated in Eosauropus. For Triassic dinosaur tracks from China and their ichnotaxonomy see also Lockley et al. (2013).

Australia

From the Blackstone Formation of the Ipswich Coal Measures of southeastern Queensland a trackway with several successive tridactyl footprints has been identified in the roof of a coal mine (Staines & Woods, 1964; Thulborn, 1998). Lucas et al. (2006) and Klein & Lucas (2021) considered these tracks as Eubronteslike. Recently the material was restudied and redocumented by Romilio et al. (2022). These authors recognise some affinities with the sauropodomorph ichnogenus Evazoum, which would be the first evidence of a Triassic sauropodomorph in this region. Other small tridactyl footprints come from a slightly deeper horizon in the Blackstone Formation and can be assigned to the ichnogenus Grallator, probably representing theropods (Thulborn, 1998; Romilio et al., 2022).

Europe

France

Most Triassic footprint assemblages in France come from the Middle Triassic. However, France has also a few sites with Late Triassic dinosaur tracks. From Carnian deposits of the Ardéche region, small tridactyl footprints called “Coelurosaurichnus” grancieri and Grallator isp. have been described (Courel & Demathieu, 2000; Gand et al., 2000, 2005). Sauropodomorph tracks (“Otozoum” grandcombensis) come from the Grés Supérieur (Keuper, Carnian-Rhaetian) of the Grand Combes area (Gand et al., 2000). They are associated with small to large theropod tracks of the Grallator-Eubrontes plexus. This is a larger surface with different trackways crossing. The assignment, in particular, of the sauropodomorph tracks is still under discussion. There is some strong similarity to Pseudotetrasauropus from the Lower Elliot Formation of southern Africa (see also Meyer et al., 2013, 2022). Footprints found in Late Triassic Keuper sediments near the city of Anduze are similar to Pseudotetrasauropus and Grallator-Eubrontes (Ellenberger, 1965; Ellenberger et al., 1970). Tridactyl footprints from Middle Triassic (Anisian-Ladinian) deposits of the Massif Central are abundantly known and have been described under “Coelurosaurichnus” and “Anchisauripus” from numerous localities as the oldest footprints of dinosaurs (Courel & Demathieu, 1976; Demathieu, 1970, 1989; Demathieu & Demathieu, 2004; Demathieu & Gand, 1972; Gand & Demathieu, 2005; Gand et al., 1976, 2000, 2005). Some have been referred to the Atreipus-Grallator plexus (Haubold & Klein, 2000, 2002; Klein & Lucas, 2021), and others might be incomplete Chirotherium. These Middle Triassic tridactyls can at best be attributed to more basal dinosauromorphs.

Germany

Germany has abundant Late Triassic (Carnian-Rhaetian) dinosaur footprints, sometimes associated with chirotherian (Brachychirotherium) and phytosaur (Apatopus) archosaur tracks, lepidosauromorph/archosauromorph (Rhynchosauroides) and therapsid/procolophonid tracks (Procolophonichnium) (Weiss, 1934, 1976; Beurlen, 1950; Rehnelt, 1950; Heller, 1952; Kuhn, 1958a,b; Haderer, 1996, 2012, 2015; Haubold & Klein, 2000, 2002). They come from fluvio-lacustrine deposits of the Grabfeld, Stuttgart, Steigerwald, Hassberge, Mainhardt and Löwenstein formations (Carnian-Norian). Common are tridactyl Atreipus-Grallator plexus footprints that can most probably be attributed to dinosauriform-theropod forms, even if some could potentially also represent pseudosuchians with a convergently developed mesaxonic tridactyl pes (e.g., Poposaurus; Farlow et al., 2014; see below). Rare components of the Late Triassic ichnofaunas in Germany are sauropodomorph tracks such as Evazoum (Haderer, 2015).

Great Britain

Great Britain mostly has Early to Middle Triassic footprint assemblages dominated by chirotheres (Sarjeant, 1974, 1996; Tresise & Sarjeant, 1997; for revisional notes on Sarjeant’s footprints see King & Benton, 1996; King et al., 2005). Late Triassic sites with dinosaur and other tetrapod footprints are found in Wales in the Mercia Mudstone Group (Norian) and in the Penarth Group (Tucker and Burchette, 1977; Lockley et al., 1996; Lockley and Meyer, 2000; Larkin et al., 2020; Falkingham et al., 2022). The dinosaur footprints are Grallator-Eubrontes (theropod dinosaur), and Evazoum and Eosauropus (sauropodomorph), the latter two were formerly assigned to Tetrasauropus or Pseudotetrasauropus [for more detailed literature and history of study see Lockley et al. (1996) and Klein & Lucas (2021).

Italy

Most Triassic footprint assemblages from Italy are Middle Triassic in age. Dinosauromorph footprints from the Middle Triassic have been reported, for example, from Anisian deposits of the Valle di Non, Southern Alps (Avanzini, 2002). The Quarziti di Monte Serra Formation (Middle Triassic, Ladinian) at Monti Pisani, Tuscany yielded a famous tetrapod ichnofauna that was described by Huene (1941) and recently revised by Marchetti et al. (2021). The latter authors list Chirotherium barthii, C. gallicum, Rotodactylus isp., Rhynchosauroides palmatus, Circapalmichnus isp. and Procolophonichnium haarmuehlensis. The tridactyl dinosauriform footprint Coelurosaurichnus toscanus represents another ichnotaxon introduced by Huene (1941) for poorly preserved material from this locality. The ichnogenus was later abandoned and synonymised with Grallator by Leonardi & Lockley (1995). In their revision of the Monti Pisani assemblage, Marchetti et al. (2021) reassigned the type material to cf. Atreipus.

A few Italian sites are in Late Triassic (Carnian-Norian-Rhaetian) strata and have dinosaur footprints. Important discoveries of dinosaur footprints come from the Carnian Montemarcello Formation near La Spezia, with the Evazoum holotype, also from the Travenanzes Formation (Carnian) that yielded both the sauropodomorph track Evazoum and the dinosauromorph track Atreipus. Other localities are in the Norian Dolomia Principale (Norian-Rhaetian), mostly showing tridactyl footprints of the Grallator-Eubrontes plexus (Sirigu & Nicosia, 1996; Dalla-Vecchia & Mietto, 1998; Nicosia & Loi, 2003; Avanzini & Mietto, 2008; D’Orazi-Porchetti et al., 2008; Bernardi et al., 2013, 2018; Petti et al., 2013; Marzola & Dalla Vecchia, 2014; see Mietto et al., 2020 for overview).

Poland

Poland has rich Early-Middle Triassic assemblages with abundant chirotheres and other tetrapod tracks, among these possible dinosauromorph tracks (Fuglewicz et al., 1990; Ptaszyński, 2000; Ptaszynski & Niedźwiedzki, 2004; Kuleta et al., 2005, 2006; Niedźwiedzki & Ptaszyński, 2007; Niedźwiedzki et al., 2013; Brusatte et al., 2010, 2011; Klein & Niedźwiedzki, 2012). Late Triassic (Carnian) strata of Woźniki in southern Poland yielded an assemblage with tetrapod footprints. Accompanied by chirotheres (Brachychirotherium), Apatopus and Rhynchosauroides, Sulej et al. (2010) report dinosauriform-dinosaur footprints they assign to cf. Atreipus and cf. Grallator. The locality is famous for vertebrate skeletal remains such as those of dicynodont therapsids.

Slovakia

The Tomanová Formation (Late Triassic, ?Late Norian-Rhaetian) of the Tatra mountains, Slovakia, yielded a larger assemblage with tridactyl grallatorid footprints. They have been assigned to cf. Grallator, cf. Eubrontes, cf. Kayentapus and Anomoepus (Niedźwiedzki, 2011). Obviously all of these are large representatives of the Grallator-Eubrontes plexus and another example of the presence of large Eubrontes before the Jurassic (sensu Lucas et al., 2006). The identification of the ornithischian track Anomoepus is doubtful. These may be extramorphological (substrate-related) variants of Eubrontes. Furthermore, reported sauropodomorph tracks are poorly preserved and could be deformed Brachychirotherium.

Spain

Spain has numerous Early-Middle Triassic sites with tetrapod footprints in the Catalan Basin, the Iberian ranges, the region of Aragon and on the island of Mallorca and elsewhere. These have different chirotheres, Rotodactylus, Rhynchosauroides, Dicynodontipus and possible Procolophonichnium, an assemblage indicating basal archosaurs, dinosauromorphs, archosauromorphs/lepidosauromorphs and therapsids (Díaz-Martínez et al., 2015; Mujal et al., 2015). Late Triassic occurrences with dinosaur tracks are rare. Pascual Arribas & Latorre Macarrón (2000) describe Eubrontes and Anchisauripus from Upper Triassic deposits at Carrascosa de Arriba in Soria Province.

Sweden

In southern Sweden the Höganäs Formation (latest Triassic-Jurassic, Rhaetian-Hettangian) yielded large material with theropod footprints of the Grallator-Eubrontes plexus (theropods) as well as an isolated footprint of possible thyreophoran ornithischian affinity (Böhlau, 1952; Gierliński & Ahlberg, 1994; Milàn & Gierliński, 2004). The assemblage occurs in fluvial-deltaic siliciclastic deposits.

Switzerland

Switzerland has abundant footprints in the Emosson Formation (?Early-Middle Triassic, ?Olenekian-Anisian) at Vieux Emosson in the western Swiss Alps. They became famous after description by Demathieu & Weidmann (1982). These authors considered part of the assemblage to belong to dinosaurs. Cavin et al. (2012) and Klein et al. (2016) showed that all of the footprints from localities in the Emosson area belong to chirotheres. Purported “dinosaur tracks” are poorly preserved and incomplete pes and manus imprints that can falsely assume a tridactyl dinosaurian shape. True dinosaur tracks have been described from the Hauptdolomit (Dolomia Principale in Italy) and Kössen formations in the Swiss canton Graubünden. These are large steep surfaces high in the Alps, in the Park Ela and Swiss National Park, showing trackways of sauropodomorphs and theropods that are similar to the ichnogenera Tetrasauropus, Pseudotetrasauropus and Eubrontes (Furrer, 1993; Meyer et al., 2013, 2022). Sauropodomorph tracks document bipedal and quadrupedal forms, suggesting the possible co-occurrence of prosauropods (?plateosaurids) and early sauropods in this region.

North America

In North America Triassic track-bearing units with abundant material and important assemblages are in the Moenkopi Group/Formation, the Chinle Group and the lower Glen Canyon Group in the western USA, and in the Newark Supergroup of the eastern USA and eastern Canada. While the Early-Middle Triassic Moenkopi Group/Formation has abundant chirotheres and Rotodactylus (dinosauromorph) tracks (Peabody, 1948; Klein & Lucas, 2010b), the Chinle Group and the Newark Supergroup (Late Triassic, Carnian-Rhaetian) are rich in tridactyl dinosaur tracks of the Grallator-Anchisauripus-Eubrontes plexus. They co-occur with Atreipus (dinosauriform-dinosaur), chirotheres (Brachychirotherium, “Chirotherium” lulli; archosaur), Apatopus (phytosaur) and Rhynchosauroides (archosauromorph/lepidosauromorph). Sauropodomorph footprints (Eosauropus, Evazoum) are rare and mostly present in the Chinle Group of the western USA. In the following we focus on Upper Triassic units that include dinosaur footprints.

Chinle Group/Glen Canyon Group

The Chinle Group has abundant tridactyl theropod footprints assignable to Grallator and Eubrontes, but also sauropodomorph tracks and trackways such as Evazoum and Eosauropus. Rare are occurrences of Atreipus (dinosauriform-dinosaur). Localities with dinosaur tracks are in Wyoming (Wind River Basin), Utah (Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and vicinity, Shay Canyon, Dinosaur National Monument area, Moab area, Colorado (northwestern Colorado, Gateway area, Colorado National Monument, southeastern Colorado), Arizona (Petrified Forest National Park, Ward Terrace,), New Mexico (Fort Wingate, Dry Cimarron Valley, east-central New Mexico) and Oklahoma (Oklahoma Panhandle) (Branson & Mehl, 1932; Santucci et al.,1995; Hunt & Lucas, 2007; Hunt et al., 1989, 2018; Lockley & Hunt, 1993, 1995; Lockley & Eisenberg, 2006; Lockley & Gierliński, 2009; Lockley & Lucas, 2013; Lockley et al., 1993, 1998, 2000, 2004, 2006a,b, 2011; Gaston et al., 2003; Lucas et al., 2010; McClure et al., 2020).

Newark Supergroup

The great Triassic-Jurassic rift valleys of eastern North America were filled with thick sequences of the Newark Supergroup, nonmarine, fluvio-lacustrine Triassic-Jurassic deposits, partly interbedded with igneous rocks. The Newark Supergroup ichnoassemblages and dinosaur tracks are well-studied (Hitchcock, 1845, 1858; Lull, 1904, 1953; Bock, 1952; Baird, 1957; Olsen, 1980, 1988; Olsen & Baird, 1986; Olsen & Huber, 1998; Olsen & Rainforth, 2001; Olsen et al., 1998; Weems, 1987, 1993, 2003, 2018; Farlow & Lockley, 1993; Silvestri & Szajna, 1993; Fraser & Olsen, 1996; LeTourneau & Olsen, 2003; Szajna & Hartline, 2003; Szajna et al., 2004; Rainforth, 2005; Lucas & Sullivan, 2006; Sues & Olsen, 2015). Theropod dinosaur footprints of the Grallator-Anchisauripus-Eubrontes plexus and Atreipus (dinosauriform-dinosaur) are abundantly preserved in this unit. Small Banisterobates from the Dry Fork Formation of Virginia is only known from the original material thus far. Rare components of assemblages are also sauropodomorph tracks of the ichnogenus Evazoum, which, thus far are known from isolated imprints only. Associated footprints are Apatopus (phytosaur), the chirotheres Brachychirotherium and “Chirotherium” lulli (archosaurs), Rhynchosauroides (archosauromorph/lepidosauromorph), Gwyneddichnium (archosauromorph) and Procolophonichnium (procolophonid/therapsid). Triassic strata with abundant footprints are found in Canada (Fundy Basin, Nova Scotia), and the USA [New Jersey-Pennsylvania (Newark Basin), Virginia (Culpeper Basin, Richmond Basin), North Carolina-Virgina (Dan River-Danville basins, Deep River Basin)]. These are in the Stockton, Lockatong, Pekin and Wolfville formations (Carnian) and the Passaic, Gettysburg and Blomidon formations (Norian-Rhaetian).

Greenland

Abundant tridactyl theropod footprints and sauropodomorph footprints have been found in the Malmros Klint and Ørsted Dal formations of the Fleming Fjord Group (Jenkins et al., 1994; Clemmensen et al., 1998; Gatesy et al., 1999; Lockley & Meyer, 2000; Milàn et al., 2004, 2006).

Tridactyls are small to large in size and can be assigned to the Grallator-Anchisauripus-Eubrontes plexus. Sauropodomorph footprints have been reanalyzed by Lallensack et al. (2017) and were assigned to the ichnogenera Eosauropus and Evazoum (see also Nieźwiedzki et al., 2014). Other accompanying ichnofauna, in particular along the Carlsberg Fjord in Jamesonland, Eastern Greenland, consists of small Brachychirotherium (Klein et al., 2015).

South America

Argentina

In Argentina Triassic deposits are rich in tetrapod footprints (Leonardi, 1994; Marsicano & Barredo, 2004; Marsicano et al., 2004, 2006, 2010; Melchor & De Valais, 2006). In particular the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin in La Rioja Province has numerous track-bearing units that are 1) the Talampaya Formation (Lower Triassic), 2) Tarjados Formation (Early-Middle Triassic), 3) Chañares Formation (?Late Triassic), 4) Ischichuca Formation (?Late Triassic), 5) Los Rastros Formation (?Late Triassic), 6) Ischigualasto Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian), and 7) Los Colorados Formation (Late Triassic, Norian). The age of the Chañares-Los Rastros formations has been debated. Based on a zircon radiometric age, Marsicano et al. (2016) re-assigned these units to the Late Triassic (Carnian), which contradicts biostratigraphic and other data (see Lucas, 2010; Lucas & Hancox, 2022). Footprints are chirotheres (basal archosaurs), tridactyl footprints (dinosauriform-dinosaur) and Rhynchosauroides (archosauromorph/lepidosauromorph). Tridactyl dinosauriform footprints come from the Chañares Formation, which also includes Grallator-like forms (Melchor & De Valais, 2006), and from the Ischichuca Formation (comparable with Anchisauripus) and from the Los Rastros, Ischigualasto and Los Colorados formations (Leonardi, 1994; Arcucci et al., 2004; Marsicano et al., 2006, 2010; Melchor & De Valais, 2006; Melchor et al., 2003). Other regions in Argentina with Triassic tridactyls and purported theropod and sauropodomorph tracks are in the Cuyo Basin (Marsicano & Barredo, 2004).

Brazil

The Caturrita Formation (Late Triassic) of Rio Grande do Sul yielded very large Eubrontes isp. footprints (pes length up to 43 cm). The Late Triassic (Adamanian) age of the Caturrita Formation is confirmed by a vertebrate body fossil assemblage in this unit (Lucas, 2010). Medium-sized tridactyl dinosaur tracks of the Grallator-Anchisauripus-Eubrontes plexus were described by Silva et al. (2008) from the Santa Maria Formation (Late Triassic) that has provided also a famous dinosaur body fossil fauna.

BIOSTRATIGRAPHY AND PALAEOBIOGEOGRAPHY

Tetrapod footprints are very useful for biostratigraphy and palaeobiogeography of continental deposits. Because evolutionary developments in the locomotor apparatus and gait are reflected in the footprints and trackways of their producers, the ichnological record provides abundant data additional to the known body fossil record. Moreover, in some stratigraphic units tetrapod footprints are the only fossils detected thus far. Some characteristic ichnospecies and morphotypes of tetrapod footprints have a restricted stratigraphic range and a wide geographic distribution and therefore can be used for a more global bio-/ichnostratigraphy. Based on tetrapod skeletons Lucas (1998, 2010) established a biochronological framework for the Triassic with different temporal units called land vertebrate faunachrons (LVFs). Lucas (2003) established a tetrapod footprint based biostratigraphy and biochronology of the Triassic, which later was modified and continued by Klein & Haubold (2007) and Klein & Lucas (2010a). Five biochrons have been proposed by these authors with some data being updated by Klein & Lucas (2024): 1) Dicynodont tracks, Induan-early Olenekian, Lootsbergian-Nonesian; 2) Protochirotherium, early-late Olenekian, Nonesian; 3) Chirotherium barthii, early-late Anisian, Nonesian-Perovkan; 4) Atreipus-Grallator, late Anisian-Ladinian, Perovkan-Berdyankanian); 5) Brachychirotherium, Carnian-Rhaetian, Otischalkian-Apachian. Only biochron 4) (Atreipus-Grallator) is based on dinosauromorph-dinosaur tracks, having a first appearance datum (FAD) in the Late Anisian. Atreipus-Grallator is also associated with Tetrasauropus, Pseudotetrasauropus, Evazoum and Eosauropus in biochron 5) (Brachychirotherium biochron) that begins in the Carnian. Therefore, dinosaur tracks from the Triassic have a very limited biostratigraphic utility if compared to chirothere tracks. Their presence in continental deposits at best indicates a Late Anisian-Rhaetian (Atreipus-Grallator) or Carnian-Rhaetian (Tetrasauropus, Pseudotetrasauropus, Evazoum, Eosauropus) age. In particular, tridactyl dinosaur tracks from the Triassic have poor resolution, and differentiation at the ichnospecies level based on anatomical features is difficult.

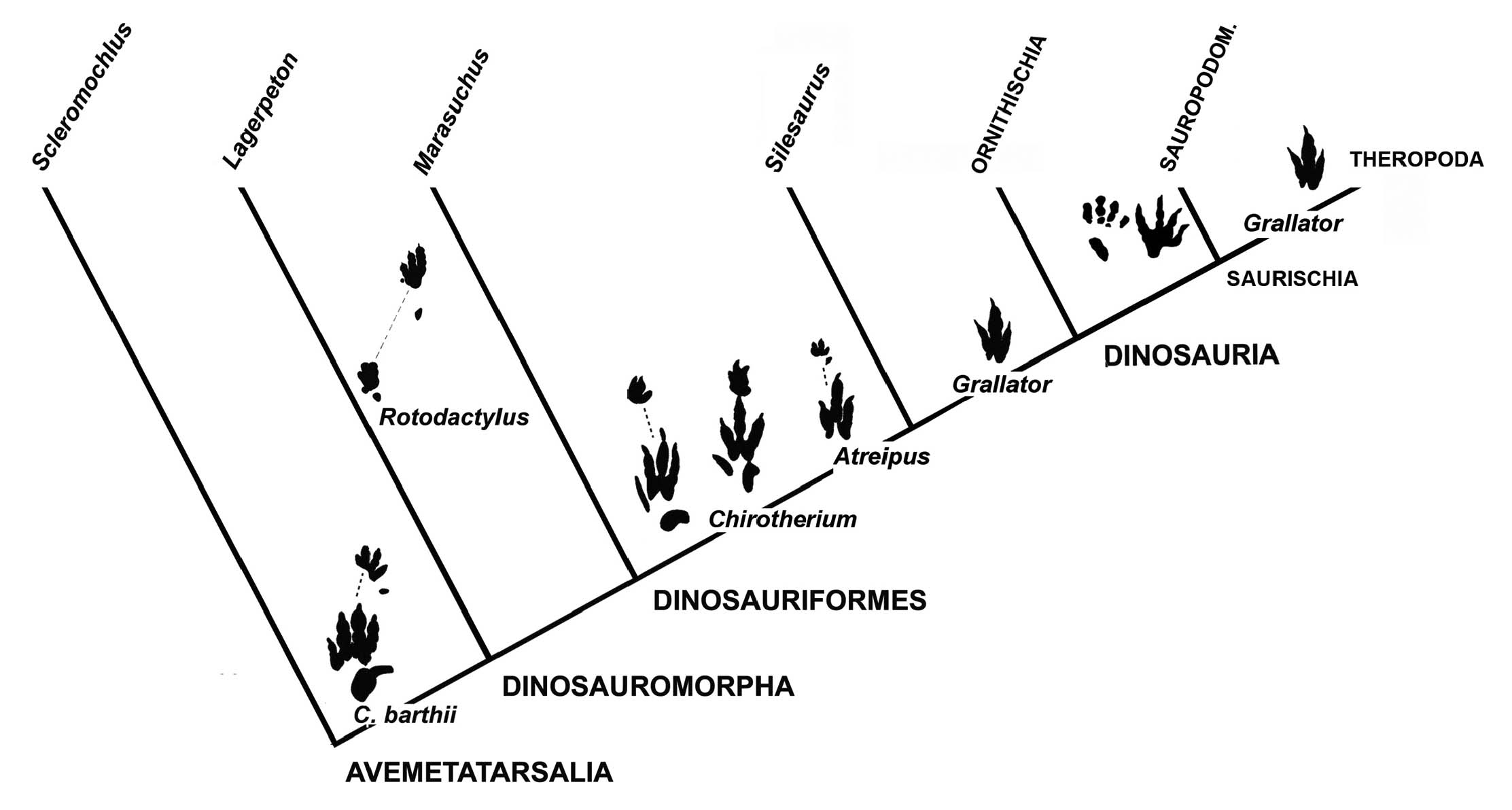

TRIASSIC DINOSAUR EVOLUTION BASED ON THE FOOTPRINT RECORD

Based on archosaur footprints the early evolution of the functionally tridactyl (“dinosaurian”) mesaxonic pes can be followed back to the early Anisian-Ladinian when the ichnogenus Chirotherium is documented from a global distribution. Haubold & Klein (2000, 2002) proposed a hypothetical evolutionary sequence Chirotherium barthii -C. (“Sphingopus”) ferox - C. (“Parachirotherium”) postchirotherioides - Atreipus - Grallator for Anisian-Ladinian chirotheres and tridactyl footprints, documenting 1) increase of reduction of pedal digits I and V, 2) increase of mesaxony in the pes, 3) reduction of manual digit IV, and 4) evolution of bipedality from quadrupedal - facultative bipedal - bipedal gait (Fig. 10). Atreipus-Grallator represent dinosauriforms and theropod dinosaurs, possibly silesaurids. There is no convincing evidence from the Triassic track record of the presence of ornithischian dinosaurs. However, it cannot be completely excluded that some tridactyls, for example Atreipus and Eoanomoepus, might represent this group (Olsen & Baird, 1986; Niedzwiezki, 2011; Lockley et al., 2018). Developments of a functionally tridactyl pes and bipedal gait are also known from the pseudosuchian Poposaurus gracilis from the Late Triassic of USA, independent of dinosaur-line evolution (Farlow et al., 2014, see above). This means that at least some Triassic tridactyl tracks could potentially be related to crocodile-line archosaurs.

- Cladogram with phylogenetic relationships of Avemetatarsalia-Dinosauria with hypothetical position of archosaur tracks treated in this paper.

The first appearance of sauropodomorph pes tracks in the Carnian corresponds with the record of skeletons (Langer et al., 1999, 2010; Buffetaut et al., 2000, 2002; Fig. 10). Stratigraphically oldest Evazoum is known from the Carnian (Nicosia & Loi, 2003; Haderer, 2015) and can tentatively be related to bipedal basal Sauropodomorpha (Lockley et al., 2006b; Lucas et al., 2010). Pseudotetrasauropus first appears in the Norian and trackmakers could be bipedal prosauropods such as plateosaurids (Klein & Lucas, 2021; Meyer et al., 2022). Tetrasauropus is from a quadrupedal sauropodomorph and known from deposits of Norian-Rhaetian age (Haubold, 1984; Thulborn, 1990; Lockley & Hunt, 1995; Lockley & Meyer, 2000; D’Orazi-Porchetti & Nicosia, 2007; Meyer et al., 2022). Eosauropus is known from Norian-Rhaetian strata and therefore corresponds well with quadrupedal basal Sauropodiformes or early sauropods (Upchurch, 1998; Wright, 2005; Lallensack et al., 2017). In particular, the entaxonic semi-digitigrade pes and the strongly laterally pointing ungual traces indicate eusauropods.

CONCLUSIONS

The Triassic dinosaur track record corresponds well with the stratigraphic and temporal distribution of the known body fossil record. Early roots of basal dinosaur-line archosaurs and dinosauriforms can be followed back to the Early-Middle Triassic (late Olenekian-Ladinian) by the ichnogenera Rotodactylus and possibly Chirotherium. Beginning in about the late Anisian-Ladinian, mesaxonic tridactyl forms appear and can be assigned to the Atreipus-Grallator plexus corresponding to dinosauriformdinosaur archosaurs. Upper Triassic (Carnian-Rhaetian) Atreipus-Grallator might represent dinosauriforms and theropod dinosaurs. The presence of ornithischians in the Triassic track record is uncertain. Sauropodomorpha are well represented by Evazoum, Pseudotetrasauropus, Tetrasauropus and Eosauropus corresponding to prosauropod and sauropodiform, possibly eosauropod members.